Willie Mays, whose prodigious power, blinding speed and eye-popping defense thrilled baseball fans coast to coast during the game’s golden era, died Tuesday, the San Francisco Giants announced. He was 93.

“It is with great sadness that we announce that San Francisco Giants Legend and Hall of Famer Willie Mays passed away peacefully this afternoon at the age of 93,” the Giants said in a statement.

Nicknamed the “Say Hey Kid” for his boundless enthusiasm and penchant for greeting everyone, “Say hey,” Mays played for 22 big-league seasons, breaking in with the New York Giants in 1951 and then becoming a fixture in San Francisco when the franchise moved west. He ended his career back in New York with the Mets in 1973.

Mays was the sport’s consummate “five-tool” talent — he could hit for a high batting average, blast home runs, gallop around the bases, catch the ball and throw it with authority.

He recorded a .301 career batting average, slugged 660 home runs, banged out 3,293 hits, amassed 1,909 runs batted in and scored 2,068 runs.

Mays’ prowess with the bat was only matched by his ability to catch any baseball hit in his zip code.

He recorded 7,112 putouts as an outfielder, topping other legends such as Tris Speaker (6,788) and Rickey Henderson (6,468). Mays also won 12 Gold Glove awards, tied for the most by an outfielder with Roberto Clemente of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

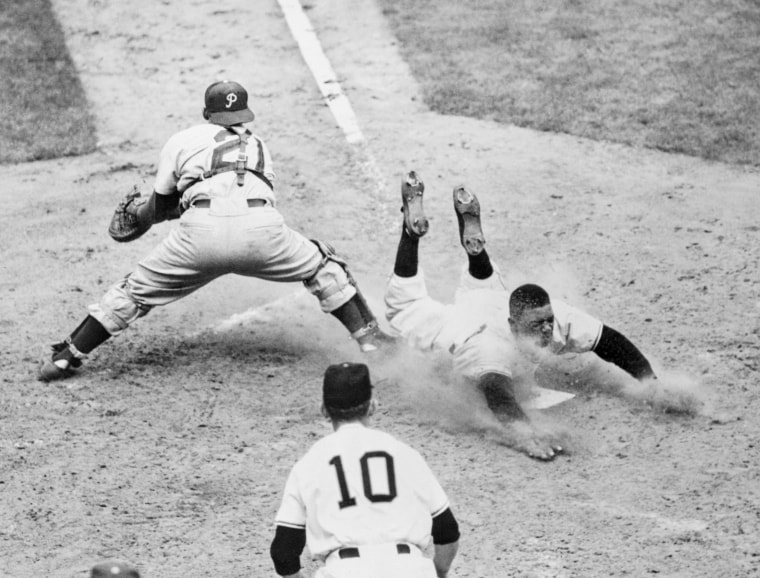

Mays is credited with making the greatest defensive play in baseball history — an over-the-shoulder snag in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, capturing a drive off the bat of Cleveland Indians slugger Vic Wertz.

Mays sprinted into deep center and had his back to home plate, 425 feet away, when he made “the catch” on Sept. 29, 1954, at the Polo Grounds in Upper Manhattan.

Hall of Fame sportscaster Jack Brickhouse called the play: “Willie Mays just brought this crowd to its feet with a catch which must have been an optical illusion to a lot of people.”

The MVP award for the best player of the World Series was named after Mays in 2017.

Major League Baseball on Tuesday called Mays “one of the most exciting all-around players in the history of our sport.”

MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said Mays had “a career and a legacy like no other” and listed his impressive accomplishments.

“And yet his incredible achievements and statistics do not begin to describe the awe that came with watching Willie Mays dominate the game in every way imaginable. We will never forget this true Giant on and off the field,” Manfred said in a statement.

“On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest condolences to Willie’s family, his friends across our game, Giants fans everywhere, and his countless admirers across the world.”

Mays played in the old Negro Leagues and was among the first generation of African American players in Major League Baseball, competing alongside and against future Hall of Fame greats like Monte Irvin (a teammate), Jackie Robinson and Ernie Banks.

Then-President Barack Obama praised Mays, a Korean War veteran, in 2015 when awarding him the nation’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“His quiet example while excelling on one of America’s biggest stages helped carry forward the banner of civil rights,” Obama, America’s first African American president, said. “It’s because of giants like Willie that someone like me could even think about running for president.”

Mays was called up to the big leagues in 1951 and made an immediate impact — winning the National League’s Rookie of the Year award for his pennant-winning Giants.

Mays had a front-row seat to perhaps the single most thrilling moment in baseball history, when teammate Bobby Thomson blasted the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” a decisive three-run homer against the Brooklyn Dodgers to win the National League pennant on Oct. 3, 1951.

Mays was in the on-deck circle when Thomson, nicknamed “The Flying Scot,” hit the homer that thrilled New York baseball fans and thousands of U.S. servicemen listening on Armed Forces Radio in Korea.

Mays said he was convinced the Dodgers would walk Thomson to face him, then a 20-year-old rookie. He was so focused on what he’d need to do at the plate that Mays said he didn’t even notice Thomson’s game-ending, pennant-winning hit.

“When Bobby hit the home run, I was the last guy to get to home plate” to celebrate, said Mays, believing the ball had been caught, “and I’m saying to myself, You’re on deck, fool, get up to the plate right away.’ ”

Mays was center stage during New York’s golden era of baseball when the Giants, Dodgers and Yankees ruled America’s pastime.

From Robinson’s rookie year in 1947 to the Giants and Dodgers final season in New York in 1957, at least one of those three New York teams played in 10 of 11 World Series.

A New York City team won nine world titles in those years, and there were six all-Big Apple Fall Classics.

And all of those great New York City teams had Hall of Fame center fielders — Mays, Mickey Mantle of the Yankees and Duke Snider of the Dodgers — leading to a generation of school kids in the five boroughs arguing over who was the best.

A 1981 song and ode to America’s pastime by Terry Cashman was appropriately titled “Talkin’ Baseball: Willie, Mickey & The Duke.”

Willie Howard Mays was born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama, the son of steelworker William Howard “Cat” Mays and Anna Mays, formerly Sattlewhite.

His father and grandfather played semi-pro baseball while his mom was a top basketball player and track athlete in high school.

By age 16, Mays was playing for the Birmingham Black Barons, the famed Negro League club. He excelled playing against grown men in their 20s and 30s.

Giants scout Eddie Montague spotted Mays and told his bosses in New York to sign him immediately.

“They got a kid playing center field practically barefooted that’s the best ballplayer I ever looked at,” Montague reported, according to a book by Mays’ future Giants manager Leo Durocher, “Nice Guys Finish Last.”

“You better send someone down there with a barrelful of money and grab this kid.”

The Giants signed Mays to a minor league deal in 1950, giving him $4,000 and the Black Barons $10,000, before he was shining under New York’s bright lights a year later.

After losing all of the 1953 campaign serving in the Korean War, Mays didn’t miss a beat in 1954.

He was that season’s National League Most Valuable Player and led the Giants to the title.

After the franchise moved to San Francisco for the 1958 season, Mays made the All-Star Game every year as a Giant and won the N.L. MVP again in 1965.

In many circles, Mays is considered the game’s greatest all-around talent despite collecting just two MVP awards. For example, Mays’ godson Barry Bonds won that honor seven times.

Although modern statistical metrics might place Mays as baseball’s third-greatest player — behind Babe Ruth and Bonds — no one could match the Say Hey Kid’s flair for the game.

“I can’t believe that Babe Ruth was a better player than Willie Mays,” all-time pitching great Sandy Koufax once said. “Ruth is to baseball what Arnold Palmer is to golf. He got the game moving. But I can’t believe he could run as well as Mays, and I can’t believe he was any better an outfielder.”

Mays ended his career back in New York, traded to the Mets in 1972.

There were occasional glimpses of past glory. His first hit for his new team was a game-winning homer at Shea Stadium on May 14 against his former Giants teammates.

However, Mays’ New York revival proved anything but a showstopper.

At age 42 in 1973, Mays couldn’t outrun Father Time and sadly became a symbol of athletes who stick around a little too long.

He was a bench player on the Mets’ improbable N.L.-winning “You Gotta Believe” team that fell to the Oakland A’s in seven games in the 1973 World Series. In Game 2, Mays chased a drive hit by Deron Johnson and fell flat on his face, a shocking sight to baseball fans who still remembered the famed 1954 Polo Ground snag off Wertz.

Later that same game, Mays lost a ball — hit by future Yankees legend Reggie Jackson — in the sun for a triple. He partly redeemed himself later in that day, hitting an RBI-single (Mays’ last career hit) in the 12th inning, as Mets went on to win Game 2 to even the series.

But Mets manager Yogi Berra had lost confidence in Mays, who got to the plate just one more time the rest of the series (he grounded out).

He was kept on the bench when the Mets went to other pinch hitters in a Game 7 loss at Oakland.

Mays dressed quickly and bitterly left the clubhouse, denied what he had hoped to be a Thomson-like moment he had witnessed 22 years earlier.

“Did Mays play too long? Of course. But so did … countless others who wanted to stretch their glory,” wrote James Hirsch in the biography “Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend.”

“But Mays is synonymous with this particular sin for one reason: He committed it in the World Series, on television. The very medium that was central to the legend, that broadcast his gifts to all corners of America.”

Even though Mays was bitter about how his playing career ended, in later years he spoke fondly of those final seasons in Flushing, Queens — with particular warmth for Mets owner Joan Payson, who engineered his New York return.

Before bringing the Mets into existence, Payson was a diehard New York Giants fan. She was on the team’s board of directors and voted against the move to San Francisco.

Mays said he wanted to hang it up before 1973, but Payson begged him to stay.

“I played the year out in ‘72 and I said, Maybe I should quit (in) ‘73 and Mrs. Payson wouldn’t let me quit,” Mays said in a 2010 interview with GQ magazine. “I enjoyed it because it was fun to see the guys winning.”

Generous to a fault and admittedly careless with money, Mays struggled in his post-playing years.

Without the structure of pro sports, Mays would be chronically late or all together miss appointments. But his name still had value and companies, such as Atlantic City hotels, coveted even the most tangential Mays connection to their properties.

Contemporary and younger fans, who pour millions of dollars into fantasy leagues and online gambling, might find it hard to believe that Mays and Mantle were both banned from MLB for several years in the 1980s for their loose Atlantic City connections.

Mays took a largely ceremonial job with Bally’s Park Place Casino Hotel in 1979 while Mantle did the same for the Claridge Casino Hotel.

MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn likened those jobs to gambling and banned them both from all big league activities.

Those revocations were overturned in 1985 when former Olympics chief Peter Ueberroth became MLB commissioner. Ueberroth recalled sitting on a Southern California beach, going over MLB files on Mays and Mantle’s banishments and failing to grasp why they were persona non grata.

“There was literally nothing there,” Ueberroth told The Los Angeles Times. “They (Mays and Mantle) had played golf at casino-sponsored outings as celebrities; they were on casino billboards, but promoting golf events, not gambling.”

He concluded: “It wasn’t even a close call. No umpire needed.”

Mays insisted his work in Atlantic City was completely blown out of proportion by Kuhn.

“I am very pleased to be back in baseball even though I didn’t do anything wrong to leave baseball,” Mays said at the 1985 news conference that heralded his return.

Throughout his career and for decades after, Mays’ name in pop culture was synonymous with greatness and the sport itself.

“Peanuts” animator Charles Schultz, a Northern California native and huge Giants fan, drew a 1966 cartoon of Charlie Brown losing a spelling bee when he was asked to spell the word maze, like the puzzle. Charlie Brown spelled it: “M-A-Y-S.”

John Fogerty’s 1985 hit “Centerfield” used Mays’ name as a metaphor for the boundless joy of baseball: “So say hey, Willie, tell Ty Cobb, and Joe DiMaggio. Don’t say ‘it ain’t so,’ you know the time is now.”

In the 1989 baseball comedy “Major League,” Wesley Snipes played fast-talking speedster Willie Mays Hayes, who introduced himself to teammates: “Say hey! Willie Mays Hays here: Play like Mays and I run like (Olympic gold medal sprinter Bob) Hayes. How ya doing?”

In a 1997 episode of “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine,” the son of Capt. Sisko searched the universe for a rookie Mays baseball card as a birthday gift for dad, showing that the Say Hey Kid was still baseball’s most famed name 3,000 years into the future.

Mays had numerous TV appearances, including on “Bewitched,” “The Donna Reed Show,” “My Two Dads” and “Mr. Belvedere.”

Despite a Hall of Fame career that played out mostly in San Francisco, Mays never forgot his New York roots.

Months after the Giants captured the 2010 World Series — the franchise’s first since leaving New York — Mays brought the Commissioner’s Trophy to P.S. 46 in Harlem, a home run’s distance away from where the Polo Grounds once stood.

“This is my neighborhood!” he told students that snowy morning on Jan. 21, 2011.

As a player for the New York Giants, Mays lived on St. Nicholas Place, blocks from work, and would play stickball with kids in the street in the mornings before and evenings after games at the Polo Grounds.

“I used to have maybe 10 kids come to my window. Every morning, they’d come at 9 o’clock,” Mays once said. “They’d knock on my window, to get me up. … So I played with them for about maybe an hour.”

When San Francisco won it all again in 2014, Mays brought the trophy to New York for a meeting with old-time Giants fans at the New York Palace Hotel on Jan. 24, 2015.

When asked how it felt to be back in Manhattan, Mays said he’ll always have a special place in his heart for New York.

“I never left,” Mays, who maintained an apartment in the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx all these years, said, bringing a roar of laughter from the crowd.

He thanked New York baseball fans: “When they like you, they love you.”

Mays married Margherite Wendell Chapman in 1956. After they divorced, he married Mae Louise Allen in 1971; both predeceased him. He and Chapman adopted one son, Michael.

Mays, who wore uniform No. 24 throughout his career, is always honored in every letter mailed to the San Francisco Giants, headquartered at 24 Willie Mays Plaza, San Francisco, California, 94107.