Kamala Harris has already made history as the first woman, the first Black person and the first person of South Asian descent to serve as vice president of the United States. If she formally secures the Democratic presidential nomination and triumphs over former President Donald Trump in the November election, she would shatter the highest glass ceiling in all of American life.

Harris marshaled overwhelming support from many party officials and raised $50 million after President Joe Biden abruptly withdrew from the race and endorsed her Sunday, but her quick ascent to the pinnacle of Democratic politics was not a foregone conclusion. In recent years, Harris has struggled to define herself on the national stage and drawn intense scrutiny from Republicans.

The dramatically altered presidential race gives Harris, 59, a high-stakes opportunity to reintroduce herself to the country. The story she might tell is one of fierce ambition and a meteoric rise through the nation’s corridors of power.

Early years

Kamala Devi Harris was born on Oct. 20, 1964, in Oakland, California, to immigrant parents who first met as civil rights activists. She has recalled attending political demonstrations as a small child.

“I like to joke,” she wrote in a tweet seven years ago, “my sister and I grew up surrounded by adults who spent their full time marching and shouting for this thing called justice.”

Harris’ parents — Jamaica-born economist Donald J. Harris and Shyamala Gopalan Harris, a scientist who was born in India — divorced when she was young. Harris and her sister, Maya, were largely raised by their mother, a breast cancer scientist who came to the U.S. from India at 19 and earned her doctorate degree the same year the future vice president was born, according to a White House profile. (Gopalan died in 2009.)

Harris attended Howard University, a historically Black college in Washington, D.C., and graduated in 1986 with a degree in political science and economics. She went back to the Golden State to attend what was then known as the University of California Hastings College of Law, earning her juris doctor in 1989.

Following graduation, Harris became a prosecutor, serving as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, where she specialized in prosecuting child sexual assault cases, and later as an assistant district attorney in San Francisco, one of the pillars of American progressivism. She cultivated a reputation for steely toughness — and soon, she worked to parlay that public persona into a career in elected office.

Political rise

Harris challenged incumbent San Francisco District Attorney Terence Hallinan in 2003, nabbing a commanding 56.5% of the vote in a runoff election and becoming the first person of color elected to the position. In the job, she established herself as a champion for LGBTQ rights and other progressive social causes, refusing to back Proposition 8, an initiative banning same-sex marriage that was overturned in 2010.

Harris received criticism from the local police force early in her tenure after she declined to seek the death penalty for a man who had killed a police officer in 2004. She ran unopposed for re-election in 2007.

Three years later, Harris ran a successful campaign for California attorney general, nabbing a key endorsement from former President Barack Obama, who a year earlier had become America’s first Black chief executive. (She narrowly defeated Republican candidate Steve Cooley.) She was dubbed “the female Obama” by some political analysts, a moniker that led some observers to speculate about her national ambitions.

In 2014, Harris married Doug Emhoff, a Southern California attorney. She is stepmother to Cole and Ella Emhoff, her husband’s two children from a previous marriage.

Harris, as attorney general of California, oversaw the largest state justice department in the country. She won a $20 billion settlement for Californians whose homes had been foreclosed on, as well as a $1.1 billion settlement for students and veterans who were allegedly preyed on by a for-profit education company. In the years ahead, Harris would point to these achievements to bolster her record as a champion of working people.

Path to power

In early 2015, Harris announced she was running for U.S. Senate after Democratic stalwart Barbara Boxer announced that she would retire following nearly a quarter-century in the seat. Harris proved herself to be an energetic campaigner and formidable fundraiser, snapping up endorsements from Obama and his vice president, Joe Biden.

Harris won election to the U.S. Senate handily, taking 61.6% of the vote against fellow Democrat Loretta Sanchez and becoming only the second Black woman to reach the chamber. She was sworn into the Senate by Biden on Jan. 3, 2017 and quickly faced a national political landscape that had been rocked by Trump’s upset victory over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential contest.

In short order, Harris styled herself as one of the Trump White House’s fiercest congressional critics, leaning on her legal skills to rhetorically prosecute the case against the new administration’s policies and political appointments. She made headlines with her tough questioning of Brett Kavanaugh during his Supreme Court confirmation hearings in 2018, and of former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

Harris frequently went viral on social media with clips of those tense confrontations, strengthening her credibility with a Democratic voter base repelled by Trump and hungry for high-profile Democrats who could push back against his agenda as part of an aggressive “resistance” to the Republican president.

The looming 2020 Democratic presidential primary gave the freshman lawmaker a chance to take that fight to the next level.

She announced her presidential campaign in January 2019 in front of 20,000 cheering fans in Oakland. She was widely seen as a possible front-runner for the Democratic nod. She presented herself as a centrist alternative to Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist, and a younger alternative to Biden, who was then in his late 70s.

In the early months of her candidacy, Harris was dogged by questions from progressive activists about her years as a prosecutor — and whether she had been too zealous in cracking down on crime, including marijuana cases. She defended her record and attempted to reassure voters that she would advocate for racial justice.

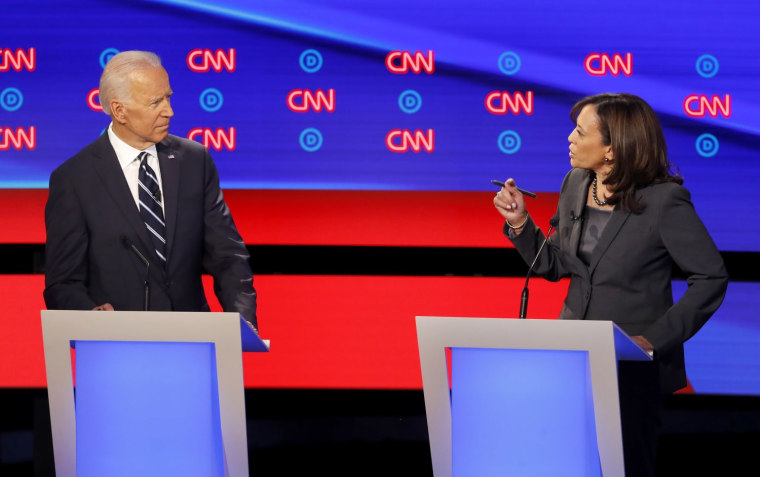

Yet after a strong start, including a debate stage confrontation with Biden over his past opposition to busing, Harris’ campaign ultimately imploded. She was rapidly running out of money, struggled to form a cohesive campaign operation and lacked a clear-cut message. She dropped out in December 2019 before any primary votes were cast.

But of course, that wasn’t the end of the story.

The veep

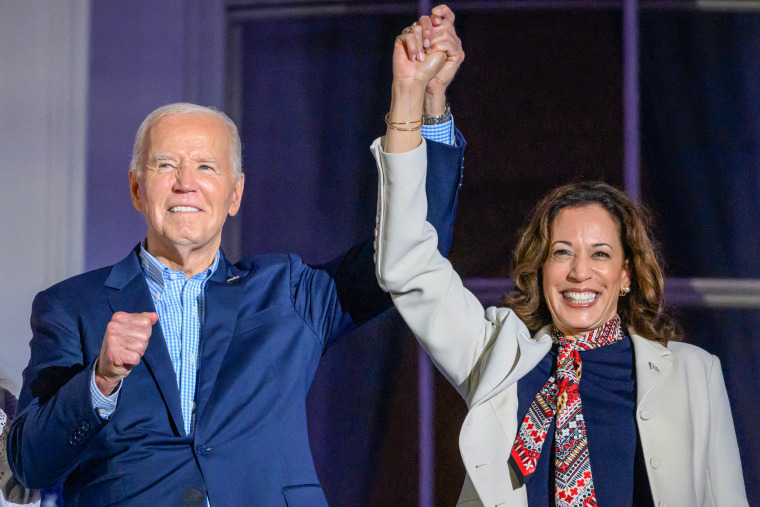

In early August 2020, Biden — who had publicly committed to selecting a woman for his running mate — announced that he had picked Harris. She became the first Black person, the first person of South Asian descent and only the third woman to be chosen as the vice presidential nominee for a major party ticket in U.S. history.

Biden, introducing Harris to the country, spoke about what her historic nomination symbolized for “little Black and brown girls, who so often feel overlooked and undervalued in their communities.”

“Today, just maybe, they’re seeing themselves for the first time in a new way, as the stuff of presidents and vice presidents,” Biden said.

In a presidential election defined by the Covid pandemic and calls for racial justice following the police murder of George Floyd, Harris worked to rally Democratic voters who were determined to take back the White House and faced off against former Vice President Mike Pence in a televised debate.

Biden and Harris proved victorious and took office in the shadow of the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol.

Harris has stood by Biden’s side amid the triumphs and crises of the last three years, from bipartisan legislative victories and the appointment of the first Black woman to the Supreme Court to the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war.

Harris has sometimes struggled to distinguish herself on the national stage, occasionally drawing mockery for speeches or impromptu remarks her critics see as awkward. Yet these moments have also helped endear her to some younger voters who circulate memes and short video clips featuring the vice president.

She has also attracted intense criticism from Republican lawmakers who have sought to link her to illegal border crossings — partly because Biden tasked her with leading the administration’s efforts to address the “root causes” of migration from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. GOP detractors have derisively referred to the vice president as the “border czar.”

Biden’s exit from the race and his endorsement of Harris put a bright international spotlight on the vice president, who quickly demonstrated she can galvanize the Democratic base with a massive fundraising haul and potentially broaden an electorate that wasn’t exactly thrilled about the prospect of a Biden-Trump rematch.

The twists and turns following Biden’s disastrous debate performance last month have been stunning, but Harris has previously indicated that the question of succession was never far from her mind.

“Every vice president — every vice president — understands that when they take the oath they must be very clear about the responsibility they may have to take over the job of being president,” Harris told The Associated Press in September. “I’m no different.”