Kate Dineen was about 33 weeks pregnant with her second child when an ultrasound revealed that her baby had suffered a catastrophic stroke in utero and would likely either die before birth or have a short and painful life.

“This was a deeply wanted pregnancy. Everything had been progressing smoothly,” Dineen, now 41, says. “I was just shocked by the diagnosis first, and heartbroken by the diagnosis, and also certain that I wanted to try and obtain a termination so that I could protect my son from pain and suffering. I knew in that moment that I wanted to make the decision.”

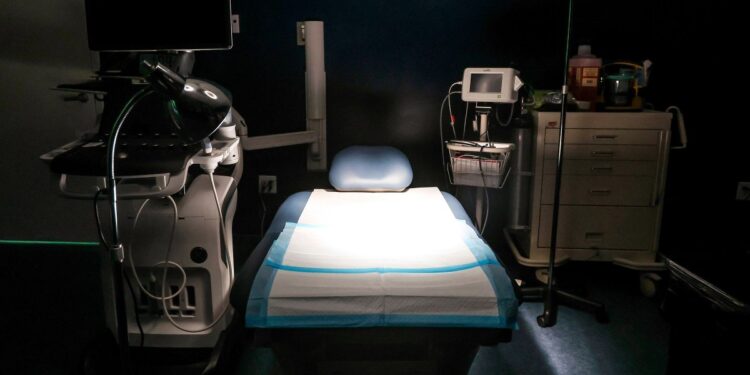

But Dineen and her husband live in Boston, Massachusetts—a state where abortion is permitted until fetal viability. While Massachusetts allows medical providers to perform abortions after that in certain situations—such as if necessary to preserve the patient’s health or life or if there’s a lethal fetal anomaly or diagnosis—doctors told Dineen in 2021 that her diagnosis didn’t fall under the exceptions under state law at the time. Instead, Dineen and her husband had to travel to Bethesda, Maryland to get an abortion.

“I was just floored that I wasn’t able to access healthcare in my home state, which I think is arguably one of the most progressive in the U.S., and also happens to be this bastion of healthcare,” Dineen says.

Abortion is legal in 29 states and Washington, D.C. Most of them, like Massachusetts, limit abortion around fetal viability, which refers to the stage at which a fetus might survive outside the uterus. In the landmark Roe v. Wade case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that pregnant people had the constitutional right to abortion, but also allowed states to restrict abortion based on the stage of pregnancy. When Roe was in place, states could prohibit abortion after fetal viability if the law carried some exceptions. Reproductive-rights organizations have said that Roe was “the floor, not the ceiling,” pushing for increased access to abortion care, and many medical organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), oppose using the term “fetal viability” in legislation or regulation. Still, only nine states and D.C. do not currently have laws that restrict abortion after fetal viability: Alaska, Colorado, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, and Vermont.

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe in 2022 with the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, 20 states have now either restricted abortion to earlier in pregnancy or banned it in nearly all situations, preventing people across the country from accessing care. But Dineen’s experience happened before Roe fell, and shows how, even in states where reproductive rights are protected, patients can still face barriers to accessing abortion services later in pregnancy.

“I was lucky that I was able to secure an appointment and receive that compassionate care and to give my son peace and to give my family peace,” Dineen says. “And many other patients are not so lucky, especially now.”

What is ‘fetal viability’?

The term “viability” is often used in two contexts: early in pregnancy, the term typically refers to whether a pregnancy is likely to continue developing normally, whereas later in pregnancy, it refers to whether a fetus could survive outside of the uterus, according to ACOG.

While fetal viability is typically thought to be around 23-24 weeks of pregnancy, doctors and medical organizations say that there is no universal point at which viability occurs—it’s an imprecise point that varies from person to person and pregnancy to pregnancy. Some pregnancies, for instance, are never viable because of complications.

“The reason that this is a difficult term to base legislation on is because it is individual to each pregnancy, and we don’t actually know if a fetus is viable until it’s viable,” says Dr. Diane Horvath, an ACOG fellow, ob-gyn, complex family planning specialist, and abortion provider in Maryland. “We can make predictions, but we can’t say at any given time that we’re certain that a particular pregnancy is viable.”

There is no test that can definitively determine fetal viability; rather, doctors will assess a variety of factors—including gestational age, genetics, and weight, among others—to predict the chances of the fetus surviving outside the womb, according to ACOG. Fetal viability is a “judgement call,” Horvath says.

Horvath says that there is no clinical justification for prohibiting abortion after fetal viability, adding that abortion is safe at any stage of pregnancy. Rather, the argument for restricting abortion after fetal viability is based on personal ethical beliefs. “I think what’s happened is people have taken this term that actually is a medical determination and, as we’ve said, unique to each pregnancy, unique to each circumstance, and they’ve made it something, politically, as if it’s a line in the pregnancy where we can always determine that a fetus will live when it’s removed from the pregnant person’s body, and that’s just not true,” Horvath says. “It is impossible to make a law that reflects all of the nuance that goes into discussing fetal viability with a patient.”

Kelsey Pritchard, director of state public affairs for the anti-abortion group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, said in a statement that the organization supports laws that prohibit abortion at 15 weeks of pregnancy or sooner, but it believes that “a viability law that actually limits abortion around 24 weeks is better than an amendment or law” that has no restrictions on abortion.

States that restrict abortion after fetal viability typically offer exceptions after that for situations where the pregnant person’s health or life is at risk, or for fatal or grave fetal diagnoses. But medical providers say that exceptions can create obstacles that make it more difficult for patients to access the care they need or want—like Dineen.

“When you look at the data of who is seeking abortion later in pregnancy, the vast majority of these cases are because of those exceptions,” says Dr. Maya Bass, a family physician, abortion provider, and co-chair of the Committee to Protect Health Care’s Reproductive Freedom Taskforce. “But I will say that anytime you have an exception, that’s an extra barrier that a patient has to prove that they are the exception to get the care, which is only further delaying their care. At some level, we need to let the patient-physician relationship remain unaffected by politics.”

Why do people seek abortions later in pregnancy?

Data indicates that most abortions occur in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy. Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that abortions performed at or after 21 weeks of pregnancy only accounted for about 1% of abortions in 2022, whereas 92.8% of abortions that year occurred at or before 13 weeks of pregnancy, and 98.9% of abortions that year occurred at or before 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Experts say there are several reasons why someone may seek an abortion later in pregnancy: they may receive a new fetal diagnosis, or they may have a health condition that worsens as the pregnancy continues. Some people could discover that they’re pregnant later, causing them to seek care at a later stage.

Another reason people may seek abortions later in pregnancy is because they faced barriers to obtaining care earlier. Horvath says that her clinic often sees patients who previously tried to get an abortion, but were unable to. Since the fall of Roe, many pregnant people have been unable to get abortions in their home state, leading to delays in accessing care if they need to travel.

When Anne Angus went for an anatomy scan when she was 19 weeks pregnant with her first child in September 2022, her medical providers found some problems. But it took a while for her to receive a full diagnosis—she had to travel from her home in Bozeman, Montana to Colorado to get more advanced maternal healthcare. When she was 24 weeks pregnant, doctors told her that her baby had Eagle-Barrett Syndrome, which is a rare condition when a baby’s abdominal muscles are weak or absent and affects the development of the urinary system and testes. Angus, now 35, and her husband decided that an abortion would be the most compassionate choice for their family.

Because Montana only permits abortion until fetal viability, Angus had to travel back to Colorado to get care. But this was just a few months after the Dobbs decision, so many clinics were overwhelmed with patients who also had to travel because of restrictions in their home states. Angus had to wait an extra two weeks before she could get an abortion.

“It was absolute hell,” Angus says. “That time, it is just so surreal because you’re still pregnant—the world still sees you and treats you as pregnant and so you have random people congratulating you, ‘Oh, when are you due?’ But your baby is going to die. And you’ve made that decision, that impossible decision, because it doesn’t feel like a choice when you get a diagnosis like that.”

Misinformation and election aftermath

In November, the country reelected former President Donald Trump, the man who has claimed credit for his role in the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling. Trump faced backlash during the campaign for his inflammatory rhetoric and false claims about abortions later in pregnancy, such as accusing Democrats of supporting doctors taking “the life of the baby in the ninth month, and even after birth.” Abortions don’t happen “after birth”—that would be infanticide, which is a crime everywhere in the U.S. And abortions later in pregnancy are rare. But medical providers, abortion-rights advocates, and patients worry that the rhetoric spread by the President-elect could perpetuate common misconceptions about abortion later in pregnancy.

“The most persistent misconception I hear is that a woman wakes up one day in her second or third trimester and decides she doesn’t want to be pregnant anymore and she flippantly, casually pursues a later abortion—that doesn’t happen,” Dineen says. “People pursue abortions later in pregnancy because they’ve received new information.”

At the same time that Trump won the presidential election, the majority of the abortion-rights measures on state ballots this year passed. Many of those initiatives only enshrined the right to abortion in state constitutions up until fetal viability.

Elisabeth Smith, director of state policy and advocacy at the Center for Reproductive Rights, said in a statement the Center believes that everyone should be able to access health care, including abortion, whenever they need it, but that “law reform is incremental,” and that local activists have a strong understanding of what language on a ballot measure would have support in their communities. Advocates behind the ballot measures have said that, because Roe protected abortion until fetal viability, voters may be more comfortable passing initiatives to restore protections with language that they’re familiar with.

After Dineen’s experience getting an abortion, she worked with advocates and lawmakers to expand the exceptions for getting an abortion after fetal viability under Massachusetts law. While she says that was a win—and is encouraged by the ballot measures elsewhere—she worries that it’s still not enough.

“Seeing states codify access to abortion is exciting, and we have momentum, and it shows that abortion still wins on the ballot,” Dineen says. “And as a later abortion patient, when I look at the actual language and see the limitations, it is heartbreaking because I know that patients like me are continuing to get left behind.”