Campaigners are urging Madrid city council not to abandon plans to create a museum on a site immortalised in a Robert Capa photograph that captured the aftermath of a fascist bombing raid in the early days of the Spanish civil war.

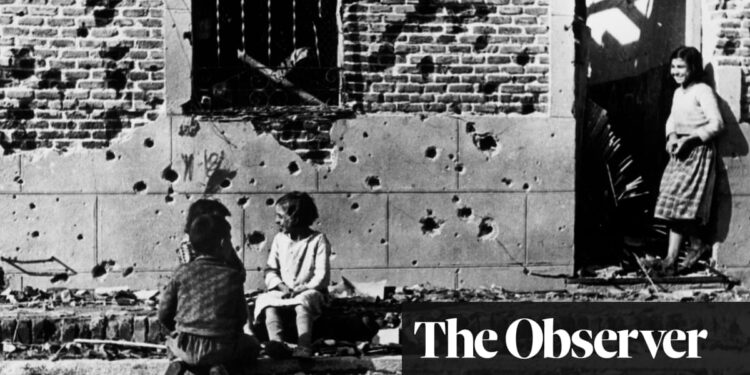

On his second trip to Spain towards the end of 1936, the Hungarian-American war photographer came across a bomb-damaged house in the working-class Madrid neighbourhood of Vallecas, its roof and facade torn with shrapnel and the street outside peppered with debris.

The picture he took of 10 Peironcely Street that winter day contrasts the devastation inflicted by one of the German or Italian bombers that were aiding General Franco’s coup with the children sitting smiling on the pavement outside, and the beaming woman who watches over them. Capa, not for the first time, had found the humanity amid the horror and the ordinary amid the extraordinary.

While the picture appeared in the contemporary US, Swiss and French press, laying bare the targeting of civilians and becoming one of the most abiding images of the civil war, it has enjoyed a long afterlife.

For the past seven years, the Save Peironcely 10 platform, backed by the trade unionist Fundación Anastasio de Gracia, has used the Capa connection to preserve the cramped, dilapidated building and to get its present-day residents into better accommodation.

In 2018, Madrid city council – then led by the leftwing mayor Manuela Carmena – announced plans to expropriate the property for €500,000 and to rehouse its tenants. Describing Peironcely 10 as a “testament to the recent history of Spain”, the council also announced plans to turn the site into a centre to commemorate what had happened there.

“When [the expropriation] process is over, our idea is that this building will become a memory centre where Robert Capa’s work could even be displayed,” José Manuel Calvo, then councillor for sustainable urban development, said at the time.

“We will of course discuss and agree the project with the collectives who have urged the protection and preservation of this building, which is so important to the memory of this city.”

Fast forward six years and the city council, now run by the conservative People’s party (PP), appears to be having second thoughts. Although the building has been expropriated and its tenants rehoused, the council’s director general for heritage told a recent council meeting that the Capa museum idea was “a conceptual proposal and not an architectural draft”.

The council has since said that no decision on the building’s future use will be made until it has been renovated. “At the moment, the council is focused on restoration of the building, which is in a very fragile state,” a spokesperson told the Observer. “Once those works have been done, a decision will be made as to the use that best fits the building’s technical conditions.”

The lack of any mention of Capa – or of a possible memory centre or museum – has stunned campaigners who fought so hard to save the building and its history.

“We feel pretty devastated after all the years and all the work we’ve invested in this,” said José María Uría of the Fundación Anastasio de Gracia. “We’ve always proposed – and we’re still proposing – that this should become the Robert Capa Centre for the Interpretation of the Aerial Bombing of Madrid.”

Uría takes particular issue with the council’s suggestion the site could serve as a multi-use cultural space. Not only is it far too small, he said, there is also a much larger cultural centre, complete with a huge auditorium, a few hundred metres away.

“It just feels disdainful,” he said. “In 2018, the city council voted to create the centre. The point here is also that no one undertakes a building project without knowing what the plan for the building and its use is. You don’t build a house and then start thinking about where the kitchen and the bathroom and all the power points are going to go. Come on! You design it according to its use. It feels like they’re taking us for fools.”

Uría points to another contradiction: in 2021, Madrid belatedly recognised the importance of the house’s history – and Capa’s image – when a copy of the famous photo went on display at the Reina Sofía museum, not far from the room where Picasso’s Guernica hangs.

“We display that photo proudly in a globally renowned museum while, at the same time, we disdain the site itself,” Uría said. “They say the site is worth preserving. But why? Why should it be preserved? It’s because of the Capa photo! Separating the building from the photo makes no sense – and [the museum] would also be a motor of economic and cultural growth for the area.”

The Peironcely house is not the only building to find itself at the centre of a political tug-of-war. In 2019, Spain’s socialist government was criticised by its opponents for removing Franco’s remains from the hulking mausoleum formerly known as the Valley of the Fallen. Last month, the central government began the process of designating the old Real Casa de Correos in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol – today the seat of the Madrid regional government – as a “place of memory” to commemorate those tortured there by Franco’s thugs.

But the idea has been rejected by the PP, which has promised to take legal action to stop the plan. “Trying to link this historical building to Francoism is a genuine disgrace,” the regional government said. “The Real Casa de Correos is more than 250 years old and has witnessed many of the events that our city and our region have lived through.”

To many inside and outside Spain, however, some buildings transcend partisan interpretations and speak of a more universal human suffering.

Cynthia Young, a former curator of the Robert Capa Archive at the International Center of Photography in New York, believes a Capa centre in the building would honour its history – and attract national and international visitors, benefiting both the barrio and the city as a whole.

Although almost 90 years have passed since Capa took his picture – and although the bombing of civilians pioneered during the Spanish civil war has become one of the hallmarks of modern warfare – his image has lost none of its potency. And nor have the bricks and mortar of No 10 Peironcely street.

“There’s an incredible power in the child’s perspective – that they’re not always the victims,” said Young.

“In some ways, I think it’s a very hopeful picture, which is so much of what Capa was trying to photograph during the war … I see it so much in the history of the building as well. It felt like most of that whole area had been torn down at one point or another during the 80s or even before, but this building stayed, for some bizarre reason.”