Donald Trump’s return to the White House will mark the end of a nascent partnership between the federal government and Native American communities on the management of federal land and water resources that are claimed by those communities. Instead, Trump has promised a raft of policies to open federal lands for business opportunities and to put more of them under private management. His pick for Interior secretary, Gov. Doug Burgum (R-N.D.), has deep connections to fossil fuel companies and makes clear the incoming administration’s intentions to open more land for oil and gas drilling.

The federal government controls nearly one-third of the country’s land area, and land under state and local government ownership adds to this total. Essentially all of those lands were previously claimed by Native Americans — and many still are. These communities have been calling for the expansion of a model of land and water stewardship that directly involves tribes in management and preservation.

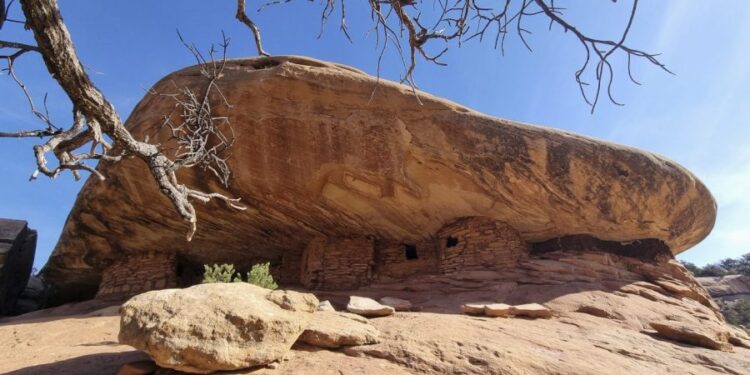

The Biden administration encouraged tribal management of several federal tracts of land in recent years. In June 2022, for example, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service formalized a partnership with a group of five tribes to co-manage Bears Ears National Monument. And last month, the government and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric administration designated the country’s third-largest marine sanctuary, the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary, off the coast of California. It was a landmark moment for indigenous communities and a win for environmental conservation in an area of rich marine life. The sanctuary will be co-managed with tribal partners, especially the Chumash people, whose ancestral territory encompasses the sanctuary.

Joint land and resource management with government partners is short of what most indigenous communities prefer. It is a far cry from the return of the territories that were wrested from them during American settlement. A thicket of thorny political and legal issues makes it unlikely that much of this territory will be directly returned to these communities in the near future, though there has been some progress in that direction.

One of the most significant recent cases involved the return of nearly 12,000 acres of federal land to the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in northern Minnesota. But this case stands out in part because of its rarity. Most Native American petitions for land returns have gone unmet.

The obstacles are far fewer in extending partnerships to indigenous groups to help manage these lands. These partnerships give indigenous communities greater land access and an ability to protect and steward what are often culturally and spiritually significant lands. This is deeply meaningful and could act as a stepping stone toward greater control over ancestral lands.

Other countries have demonstrated a path toward making this work at a far larger scale than has occurred in America. Australia has given its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities land management and stewardship roles around the country in recent years. First Nations people now have rights or ownership in slightly over half of Australia’s land.

The degree of control varies. Some communities, such as the Yolngu on the eastern coast of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, have achieved rights approximating ownership in key areas such as Blue Mud Bay, a culturally significant bay that is also a productive commercial fishery. Others, like the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people in Queensland, have returned to managing ancestral lands in partnership with the government.

South Africa has moved in the same direction since the end of apartheid. Alongside a large program of land restitution and land reallocation to Blacks who suffered forced removals during apartheid, the government has also partnered with indigenous communities to manage lands and resources where outright land returns are impractical for political or economic reasons. For instance, the government has recognized claims by the Makuleke people to ancestral homelands within Kruger National Park and has partnered with them to manage portions of the park.

Partnerships for indigenous land and water management can also provide revenue opportunities for these communities. In Australia, one-quarter of permit revenues to visit the famed Uluru rock formation, also known as Ayers Rock, at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park goes to supporting the Aboriginal community that calls the area home. Arrangements like this can provide indigenous communities with much-needed resource streams to help reconstitute frayed tribal life and languages in the aftermath of decades of disruptive and destructive settlement policies.

Opportunities to cultivate partnerships like these abound in America given the nation’s vast collection of federal lands and waters. In addition to their cultural importance, these partnerships also represent an economic opportunity for tribes that aim to nurture their tribal memberships and steward their ancestral homelands.

It is a simple and long overdue first step in repairing relationships with the traditional inhabitants of the land. But it is one that is poised to halt under the second Trump administration.

Michael Albertus is a professor of political science at the University of Chicago and author of the forthcoming book “Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn’t, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies.”