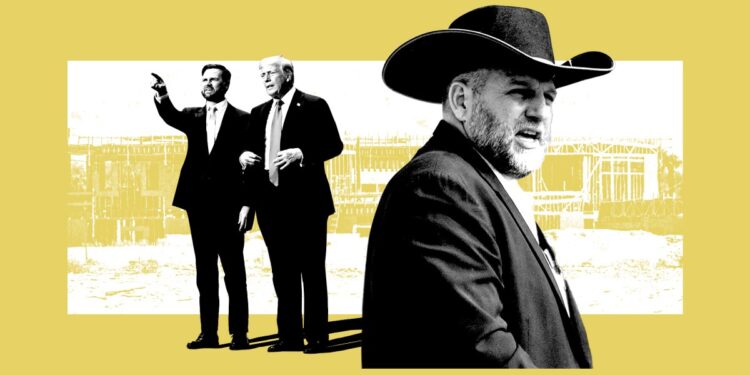

During the vice presidential debate, CBS news moderator Margaret Brennan pressed Ohio Sen. JD Vance about former President Donald Trump’s proposal to seize public lands to use them for housing construction. “Senator, where are you going to seize the federal lands?” she asked. “Can you clarify?”

“Well, what Donald Trump has said is we have a lot of federal lands that aren’t being used for anything,” Vance replied. “They’re not being used for national parks. They’re not being used. And they could be places where we build a lot of housing.”

Vance was referring to an idea Trump floated in 2023 when he announced that his next administration would solve the nation’s housing crisis by holding a contest to charter 10 new “freedom cities” on public land. “These freedom cities will reopen the frontier, reignite American imagination, and give hundreds of thousands of young people and other people, all hardworking families, a new shot at home ownership and, in fact, the American dream,” he said in a video announcing the proposal. (In the same video, Trump also pledged to solve the country’s transit woes with flying cars.)

Whether he realized it or not, Trump’s ”freedom cities” put a new face on an old pet cause of Western conservatives and Sagebrush Rebellion sympathizers. For years, these anti-government activists have been agitating for the federal government to sell off public lands or place them under state control. But affordable housing has never been part of their agenda. After all, most public land out West is in remote places with little water and infrastructure, and where few people want to live. (Dunn County, North Dakota, anyone?)

The push to sell off public lands has long been backed by big corporations seeking cheap land for grazing, oil and gas drilling, or coal and uranium mines, all free from many federal environmental regulations. Even so, Trump isn’t the first politician to propose using public land for housing. The idea was most recently, and most prominently, brought into circulation by the far-right agitator Ammon Bundy.

He’s the son of rogue Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, who engaged in a 2014 armed standoff with the Bureau of Land Management when the agency attempted to impound cows he’d been illegally grazing for years on federal land. Two years later, Ammon Bundy orchestrated the armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, a confrontation that ultimately led an FBI agent to fatally shoot one of the occupiers, LaVoy Finicum. Bundy was tried twice for his role in the standoffs. The first case, in Nevada, ended in a mistrial after misconduct by the government. A jury in Oregon ultimately found him not guilty of the Malheur occupation.

The confrontations—and the failure of the Justice Department to punish him—turned Bundy into an outlaw hero to those who oppose federal control of public lands in the West. After instigating protests against Covid restrictions during the pandemic, in 2021, he leveraged his fame into a political campaign and announced he was running as a Republican for governor of Idaho. And that’s when his housing policy came into play. Bundy stumped heavily on using public lands in Idaho to help state residents buy affordable homes. On his campaign website, he wrote:

If we are going to maintain our historic and traditional values, and ultimately Keep Idaho IDAHO, we must spread out and make Idaho’s land available to the people while simultaneously ensuring that necessary land remains public land for multiple use purposes (under local jurisdiction). Then we can enjoy the fruits of prosperity and land ownership while maintaining our culturally conservative identity.

The current affordable housing crisis is caused by a number of complicated factors, many of which have been caused by the Federal Government. Nevertheless, at its core, this crisis is simply a supply-and-demand issue. To lower prices, we simply need more supply. And to have more supply, we need to take our land back.

“I’m not sure if Ammon Bundy pioneered the idea of seizing public lands to create more sprawl, but he definitely leaned hard into it when he was running for governor of Idaho,” says Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the nonprofit Center for Western Priorities, who has followed Bundy’s career for many years. “Sometimes terrible ideas come back around with a fresh coat of lipstick, but it’s still the same old land-seizure movement.”

“Sometimes terrible ideas come back around with a fresh coat of lipstick, but it’s still the same old land seizure movement.”

Bundy’s proposal made news, but it didn’t do much for his campaign. After losing the GOP primary to the current sitting governor, Brad Little, he ran as an independent in the general election in 2022 and lost again. But Bundy seemed fairly sincere about wanting to build housing on public lands. In interviews, he said his own adult daughter was struggling to afford a house in Boise’s overheated housing market. (He’s also not a Trump supporter. He criticized the former president in 2018 for his hateful anti-migrant rhetoric.)

Trump’s housing plan, however, seems much more like cover for the same old agenda pushed by Republicans from Reagan to George W. Bush. It boils down to a simple premise: giving away public lands to fossil fuel companies and other extractive industries that want to plunder them on the cheap. Indeed, people hoping to shape the next Trump administration’s public lands policy have not demonstrated much interest in housing in the past.

Take William Perry Pendley, who served as the acting BLM director during the Trump administration for more than a year despite never getting confirmed by the Senate; he even ignored a ruling from a judge who said he had to leave the job because he was serving illegally. When Trump tapped him as acting BLM director, Pendley released an extensive recusal list of former clients in the oil, gas, and mining industries.

Pendley has been arguing in favor of the fire sale of public lands since he served in the Reagan administration working for the infamously anti-environment Interior Secretary James Watt. The author of Sagebrush Rebel: Reagan’s Battle With Environmental Extremists and Why It Matters Today, Pendley was involved in an agency scandal over leasing land to coal companies at bargain basement prices.

During the 2014 armed standoff at the Bundy ranch in Nevada, Pendley wrote a column in National Review expressing support for the embattled rancher and his fight with the federal government. “Westerners are tired of having Uncle Sam for a landlord,” he complained. Two years later, Pendley wrote again in National Review, “the Founding Fathers intended all lands owned by the federal government to be sold.”

More recently, Pendley authored the Interior Department section of Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s blueprint for a new Trump administration. It outlines 28 pages of proposals for turning over more public lands to unfettered oil, gas, and mineral development, including in sensitive areas from Alaska to Minnesota. But suddenly, Pendley has become an affordable housing advocate. In July, he wrote an op-ed in the Washington Examiner headlined “Solve the housing crisis by selling government land.”

Strangely enough, using public land for housing is a rare point of agreement between Trump and President Joe Biden—sort of. After all, the Biden administration has already done it. In July, the BLM announced the sale of a small 20-acre parcel in the Las Vegas Valley for the specific purpose of developing affordable housing. The land would be sold cheaply to the Clark County Department of Social Services, with strict requirements about how it can be used. Eighty percent of the housing must be sold to first-time homebuyers with household incomes at or below 80 percent of the Las Vegas area median income, for instance, and the rest will go to first-time buyers at or below 100 percent of the area’s median income.

“The Biden administration just called the bluff of land transfer proponents,” Weiss said in a statement at the time. “The Interior Department is showing how public lands that are already well-suited to development can be part of the housing solution, with appropriate safeguards to make sure the housing is affordable and doesn’t end up as trophy homes for billionaires.”

Bundy doesn’t seem to have weighed in on the Trump “freedom cities” proposal. He’s been a little busy dodging the payment of a $50 million defamation judgment against him, the result of an armed protest he organized in 2022 against an Idaho hospital he falsely claimed had kidnapped the baby of one of his supporters. (Social workers had taken the baby in for being malnourished.) After the jury verdict last year, Bundy took his family and went into hiding. The hospital seized his house to help pay the judgment. Bundy later resurfaced at an undisclosed location somewhere in Utah.

While he too may need some affordable housing, it’s not clear that he’d be a fan of Trump’s “freedom cities.” After all, Bundy despises cities. “History and human nature demonstrate that if we go down the path we are on now and build up and create dense and congested cities with large populations, traffic, and pollution, we will lose our conservative, traditional values,” he wrote on his campaign website in 2021. “It’s just what happens.”