The day after the assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump in July, Pastor Diane Mullins took the microphone in front of the southwest Ohio church she and her husband, Jim, preside over and began to pace in front of a large LED screen with the graphic of a billowing American flag.

“I’m tired of holding back because I’m running for a stupid office, and I don’t care if they hear that,” she said, her voice slowly rising. “The only reason I’m running, it’s about the kingdom of God and his righteousness that should rule and reign in the government of the United States of America.” Her cadence quickened, the electric organ and audience’s applause swelling to meet her fever pitch as her words turned into commands. “It is time for the godly, it is time for the anointed of God to arise! Awake! Arise! Advance! Be the church. Stop being afraid!”

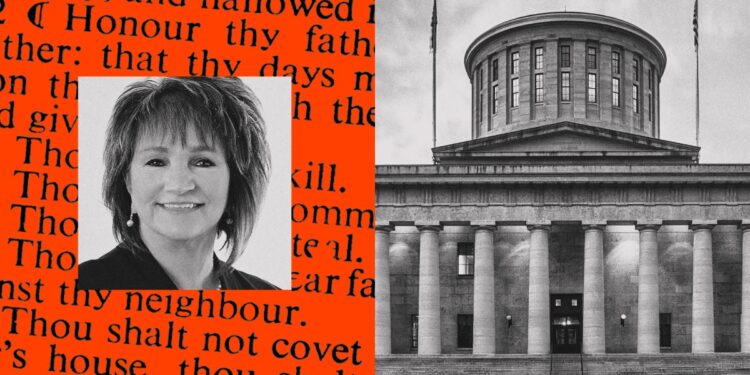

From the city of Hamilton, population 63,000, the urban center of a mostly rural county, Mullins is running a statehouse campaign in which she presents herself as a mainstream Ohio Republican, running to defend “conservative values.” But when she appears before her hundreds of congregants, Mullins has been much more explicit about the interdependence of faith and politics. “The principle of separation of church and state is a lie,” she said in a 2021 sermon. “The Constitution of the United States was written by men who were Christian men, who were principled men, because they were concerned that one day, the government would try to take over the church and the Christians.”

A Christian nationalist gospel that might have once been a fringe of the Republican Party now commands a central role, from Speaker of the House Mike Johnson to down-ballot races across the country—to school boards and local government. Should they be elected, their mission is to infuse government with the word of God.

“It’s this belief that while the United States might have different people, different races and ethnicities or religions, it was built by white Anglo-Protestants,” says Andrew Whitehead, co-director of the Association of Religion Data Archives at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “And those folks today who are white Anglo-Protestants really have the clearest heritage to help run this country, to have a say in what it should look like.”

“From three to four years old, if you would say, ‘What do you wanna be when you grow up,’ I would tell you I was gonna work for Jesus.”

The child of devout Christians, Mullins always felt certain of her destiny. “From three to four years old, if you would say, ‘What do you wanna be when you grow up,’ I would tell you I was gonna work for Jesus,” Mullins said on the Christian radio show Shaped by Faith, in 2018. But she figured her vocation was to support a ministering husband, in much the same way her mother did for her father, Pearl Robinson, a Pentecostal pastor in the Cincinnati suburb of Hamilton, where Mullins lives today.

For years, Mullins was Jim’s supportive spouse, when he took over what was then called the Calvary Christian Center in Hamilton from his parents. But over three consecutive nights in 2015, Mullins says, messages from God interrupted her sleep. On day one, he said, “Awake. Arise. Advance.” On the second, he said, “Honeybee.” And on the third, “Deborah.”

A biblical figure who was Israel’s first female judge and prophet, Deborah, or “Honeybee” in Hebrew, appears in the Book of Judges and guided an Israeli warrior to lead 10,000 soldiers to defeat an army of Canaanites (people who lived in what is now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine). In the “Song of Deborah,” she is commanded by God to “awake” and “arise” as a “mother in Israel.” For Mullins, these divine messages and the spectacle of what she described as “the nasty women’s march” after Trump was elected in 2016, convinced her to start a ministry called Deborah’s Voice. Aspiring to be “the voice of Christian women,” the ministry’s priorities include “ending abortion,” “protecting traditional marriage,” and “supporting Christian women in politics.” Starting in 2018, Deborah’s Voice even held rallies across the country. “We just feel that women have a voice in this nation, and we don’t want the wrong voice,” Mullins told the Christian Post ahead of the ministry’s 2018 rally in Washington, which was attended by a few hundred people.

Devoted Christian nationalists tend to be comfortable with the idea of authoritarian social control, Whitehead tells me. The logic goes that chaotic circumstances require rigid rules, and strong leaders like Trump to enforce them, to restore the order that people crave. Mullins views America’s founding documents as sacred and needing protection from change. Meanwhile, the devil—via the so-called “deep state”—has been working internally to thwart God’s plans.

“It’s this belief that while the United States might have different people, different races and ethnicities or religions, it was built by white Anglo-Protestants.”

The story of Deborah has often appeared in Mullins’ sermons over the years, especially to underscore the significance of a female prophet who was not only trusted but revered. “She was where I believe the church is today,” Mullins preached in September. “We are a righteous people in between the established church and the world, the culture that we live in, that is so ungodly and unrighteous.” Within this context, Mullins says, around November 2023, God once more directed her, this time to campaign for office and serve him in the Ohio House of Representatives as a representative from the solidly red 47th District. Running for office wasn’t her decision, she says, it was God’s. His timing was propitious: November 2023 was when Ohioans voted to legalize recreational cannabis and constitutionally protect abortion. “Everything is about the kingdom,” Mullins said in a January sermon. “So, what is it about the kingdom that God wants to use me for in that?” Mullins’ campaign did not respond to Mother Jones’ interview requests or questions.

This was not Mullins’ first statehouse campaign. Four years ago, before Ohio enacted new legislative maps, she unsuccessfully challenged a different Republican incumbent, telling southwest Ohio newspaper the Journal-News that she was a pro-gun, anti-abortion candidate who wouldn’t compromise her “conservative core beliefs.” What is new, however, is the amount of dark money that she has received, which helped her—like the biblical David—defeat the political Goliath in the primary against three-term incumbent Rep. Sara Carruthers. Make Liberty Win, a Virginia-based hybrid PAC/super-PAC that seeks to elect “liberty-defending” state lawmakers, poured more than $96,000 into supporting Mullins (and opposing Carruthers), $40,000 more than Mullins’ own campaign spent.

By February, the race got ugly, culminating in Carruthers filing a complaint against Make Liberty Win with the Ohio Elections Commission for mailing attack ads without disclosing it was the source. The ads claimed Carruthers “threw a single mother out of her house,” referring to a complicated story in which the surrogate of Carruthers’ two children filed a breach of contract suit against the candidate. Carruthers settled the lawsuit out of court in 2022 and the case is now sealed. (Mullins told the Journal-News in February that “I would never OK a mailer like that.”)

Make Liberty Win spent more than $1.8 million in about a dozen GOP primaries in Ohio, mostly to oppose Republican incumbents, part of the so-called “Blue 22,” in favor of more MAGA-minded candidates unwilling to compromise with Democrats. Eight of the 12 challenged Blue 22 Republicans held onto their seats. But the challengers who did win, like Mullins, presented themselves as being much more hardline conservatives, each highlighting their devotion to Christian values. Ty Mathews, for example, running to represent Ohio House District 83, has three pillars guiding his campaign: God, country, and family. “There’s a reason why [God] is number one,” Mathews explains in a video on his campaign website.

The inflexibility and radical nature of their respective candidacies seem to ignore the fact that Ohioans, including Republican voters, have rejected the state GOP’s efforts to stifle more progressive policies, says Paul Beck, a professor emeritus of political science at Ohio State University. “There’s an old adage in politics that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” he tells me. “We’re seeing that with these Republican supermajorities. Many of their members now think they can really do anything.”

“Everything is about the kingdom. So, what is it about the kingdom that God wants to use me for in that?”

Mullins hasn’t publicly campaigned much since securing the Republican nomination, trading stump speeches and meet-and-greets for private fundraising events and occasional appearances at county fairs and holiday parades. She doesn’t have a campaign website or a WinRed fundraising page. And aside from references to supporting the Second Amendment and opposing abortion, her policy platform is scant. On her candidate Facebook page, she blends patriotic posts with praise and prayers for Trump, and images of her hobnobbing with Donald Trump Jr. and the GOP’s US Senate candidate in Ohio, Bernie Moreno.

Despite her proclivity for conspiracy theories, Mullins has been relatively mum on immigration—which is striking given the national spectacle Trump and his vice presidential hopeful Ohio Sen. JD Vance have created with disproven claims about Haitian immigrants eating pets. Springfield is about an hour north of Mullins’ district, and Trump and Vance’s falsehoods have, as Republican Gov. Mike DeWine put it, made the community the “epicenter of vitriol over America’s immigration policy.”

Mullins’ political base of operations appears to be inside Calvary Church, a medium-sized brick building adorned with a large cross and a looming white steeple. Every Sunday, worshippers gather in a large auditorium, led by a live contemporary rock band and a chorus of singers. Pastors encourage the unsaved in the audience to make themselves known and receive God. Calvary Church weaves nondenominational teachings with elements of Mullins’ Pentecostal upbringing; she speaks in tongues, for instance, and congregants line up for some faith healing from her and her husband.

For years, Mullins has warned people in her church of the impending end times, pointing to evidence that seemed to be everywhere: Satan “pervert[ed] what male and female was all about” in society. The culture’s ungodliness ushered in the spread of the “man-made” coronavirus. The Antichrist has infiltrated American institutions through communism. From her pulpit, she emphasizes this church’s unique role in bringing the unsaved into the Lord’s “harvest” before Jesus’ return, casting out the ever-present “enemy,” and aligning the United States with the Holy Word.

One Sunday morning this past summer, less than 5 miles down the road from Calvary Church, Mullins’ Democratic opponent, Rev. Vanessa Cummings, was preaching at Payne Chapel AME Church. As Cummings finished delivering her sermon to the dozen or so people in the pews, she emphasized the need to pray for unity, world peace, and healing from divisiveness. She’s been a pastor at this 184-year-old Black church for three years and has ministered across the state. A longtime public servant and community activist, she served as vice mayor and city councilmember of nearby Oxford and is the vice president of Oxford’s NAACP chapter. She has long helped with voter registration and education drives. Today, I am the only white person in the room and I am reminded of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous observation that 11 a.m. on Sunday was the “most segregated hour of America.”

Sitting across from me in her office after the service, Cummings acknowledges that in a district that is nearly 62 percent Republican, the odds are stacked against her. But, she notes, “If I didn’t think I could win, I wouldn’t run.” The voters she’s spoken to on the campaign trail are desperately seeking change, Cummings tells me, and they’re tired of politicians making decisions against their constituents’ wishes because of their personal beliefs.

While her faith guides her in her personal life, she emphatically rejects the tenets of Christian nationalism that Mullins preaches. “She believes there’s no separation of church and state. I believe there is a separation of church and state,” Cummings says. “She believes this is a stupid position. I believe it’s a position we should fight for, to get to serve the people.”

“It’s good I’m not God, I’d kill ‘em, every one.”

A few hours earlier, as I sat in a back pew as hundreds of people filtered into Mullins’ Calvary Church, a countdown timer inched toward zero on the three LED screens on the wall behind the pulpit. With a couple of months before the election, Mullins’ sermon was far less political than many of the ones I’ve watched on the Calvary Church YouTube channel. Her message was simple: God does not care what sins you have committed in your past, as long as you believe that Jesus Christ is your savior and you devote yourself to living in line with God’s word.

As forcefully as she has condemned the “perversion” and “unrighteousness” in society, in this sermon she emphasized this church would welcome, with open arms, a homeless drug addict or “two men who come in holding hands” who hope to hear the Lord’s good news. Similarly, people struggling with sins like “abortion, unforgiveness toward an abuser, fornication, sex before marriage” and “pornography” should not be afraid to accept Jesus into their hearts. It’s Mullins’ twist on the common refrain “Love the sinner, hate the sin.”

It can be hard to reconcile that message with the image of the devilish “enemy” she regularly evokes. And it is the proliferation of sin, she preaches, that prevents the full realization of God’s visions for the world. “There’s too much darkness, too much deep state, too much sexual sin, too much abuse,” Mullins said in 2020. “And every day, I go: Oh Lord, Jesus. And he says, ‘I’m just letting you see it, I’ve known it all along.’ You know what my next thought is? It’s good I’m not God, I’d kill ‘em, every one…We need God. Thank God we’re not him, because we’d probably all be dead, too.”