On the last day before the start of early voting, Kristian Carranza, a 34-year-old Democratic candidate for the Texas House of Representatives, and David Hogg, the gun control activist from Parkland, Florida, were discussing lessons they’d learned about door-knocking as they went door to door in a neighborhood of big trucks and single-family homes on San Antonio’s Southside.

The yapping dogs are mostly harmless. “No soliciting” signs are not to be ignored. And the knock itself is a delicate science. (The city’s mayor, with whom Carranza had recently campaigned, swore that the optimal wait time was exactly 7 seconds between knocks.) In neighborhoods like this, people often kept their front doors open but the screen doors shut.

“On the Northside, there’s so many more Ring cameras,” Carranza said. “I’ve never had so many Ring conversations knocking doors than I have this year.” Sometimes, she’d have an entire conversation without anyone ever opening the door.

“There’s a path to holding the line against private school vouchers, and the path runs through House District 118.”

When doors do open, Carranza led with a simple pitch.

“I’m running to put more money [into] funding our public schools,” she told a middle-aged man a few houses down from where we’d started. “So many of our schools are closing. We’ve had some schools closed in Southside [Independent School District] as well, and we have to do everything we can to keep our little ones in school.”

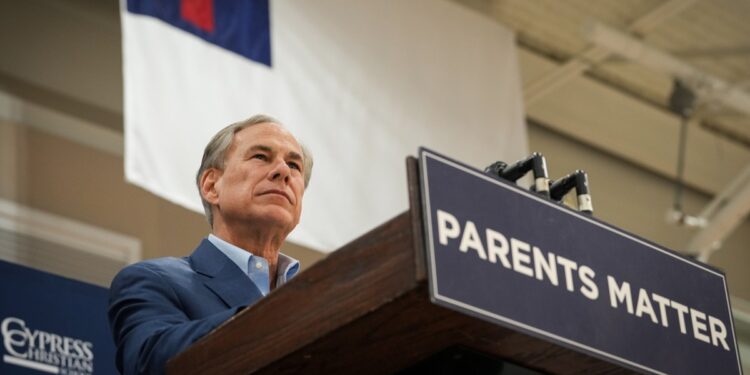

Carranza’s pledge to protect education funding was not an idle bit of boilerplate. Her campaign in state House District 118 is a small race with potentially enormous stakes: The fight for votes here could help make or break Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s push to create a taxpayer-funded voucher program, which would allow parents to create “education savings accounts” to fund private school tuition or homeschooling. The proposal, which has been a priority for many conservatives in the state for decades, has been defeated in two consecutive special sessions—thanks, in part, to opposition from rural Republicans who feared that it would lead to closures and consolidation in small school districts. But during the Republican primaries this past spring, Abbott and allies spent more than $10 million to oust the bill’s opponents. He believes he now has the votes—unless Democrats can knock off enough voucher supporters this fall. To do that, they must defeat Carranza’s opponent, Republican state Rep. John Lujan. Carranza expects the race to come down to just a few hundred votes.

Four years ago, Democrats talked about flipping enough seats to win control of the state House of Representatives. Instead, they picked up just one. This time around, their ambitions are more modest. Monique Alcala, executive director of the Texas Democratic Party, told me the party needed to flip three seats—the number they think they’d need to stop a voucher bill from passing. The 118th, which forms a half-eaten U along the lower edges of Bexar County and stretches into the historically Mexican American and Democratic neighborhoods of the Southside, is one of the most winnable of their targets on paper. But the precinct Carranza and Hogg canvassed, like much of the district, shifted significantly toward Republicans during the Trump era. It was the only state house district that voted for Joe Biden in 2020, Beto O’Rourke for governor in 2022, and a Republican to the legislature the same year—Lujan, a former San Antonio firefighter and sheriff’s deputy, who is finishing his first full term in office.

The high stakes have made the district a magnet for outside spending. Hogg’s group, Leaders We Deserve, which bills itself as an “EMILYs List for young people,” has poured more than $1 million into the race, hoping to both elevate a millennial progressive and in the process send a message to Abbott, who declined to support gun control legislation in the wake of the 2022 mass shooting at a school in Uvalde.

“There’s a path to holding the line against private school vouchers, and the path runs through House District 118,” Carranza told me, as she sipped a Coke in the back of an ice cream shop near her campaign office. She said she believes Abbott’s reforms are a “scam.” They “would be devastating to the public education system in Texas,” she said, and, as evidence, pointed to a similar program in Arizona—where a “school choice” law has mostly benefited wealthy families who already had abandoned the public education system, while subsidizing religious institutions and, in one infamous case, the purchase of dune buggies.

Carranza’s political platform is rooted in her experience as a community organizer. She went door to door in these same neighborhoods to encourage residents to apply for health coverage under the federal Affordable Care Act.

“This is a very low-income, working-class, middle-class neighborhood; these are not the type of communities that are going to benefit from a voucher program,” Carranza said. “The $8,000 voucher won’t be enough to get a child into private schools, to be able to afford tuition and uniforms, and travel to get to the schools—because they don’t provide travel and all the little things that I think we don’t always think about that schools provide.”

As she sees it, Abbott’s bill would only exacerbate an existing crisis, by taking money and students out of the system. In the Harlandale Independent School District, she said, referring to the district we were sitting in and where she grew up, “we had four elementary schools closed just this past spring. The fight against private school vouchers is a lived reality for people that live in this district, and when we talk about schools closing, it’s not just schools, because for families in these communities, we don’t just look to our public schools for quality education.” Close public schools, and you close after-school activities and free lunch programs, too. It was an attack on a deeper social safety net.

Lujan, for his part, has argued that while he supports vouchers, he does not support taking funds out of public education and emphasized the need for oversight of private schools that receive public funds. Although he has voted for Abbott’s measures in the past, he said at a recent debate that he would approve a school-choice bill in the next session only if it included new standards for assessing how well private schools are performing. But Abbott, for one, doesn’t seem troubled by where the Republican stands; the governor came to the district last week to stump for him.

The voucher fight may be the most immediate challenge in the legislature, but Carranza’s campaign has been shaped by Texas Republicans’ decadeslong push to eliminate abortion rights. She traced her decision to work in politics to state Sen. Wendy Davis’ 13-hour filibuster of the state’s sonogram law in 2013, which Carranza watched on the floor at her mother’s home, glued to a YouTube stream on her laptop. Since then, Texas’ restrictions have gotten more severe. Carranza is running hard against the state’s post-Dobbs abortion ban, which makes abortion illegal except to protect the life of the mother. (In practice, the restrictions have done the opposite; NBC News reported last month that the maternal mortality rate jumped 56 percent in the state from 2019 to 2022.) Lujan has taken a far different stance.

“If it was my daughter, I don’t have any daughters, but if I had a daughter, and that would have been, you know, it would have been a rape, I think we, as a—personally—I would say, ‘No, we’re gonna have the baby,’” Lujan said during a local radio interview in September.

That comment wasn’t just callous, Carranza said. It missed a key bit of context. “I think we have to be very clear about this: In the state of Texas, no woman is allowed an abortion if she is a victim of rape,” Carranza said. “And I think that that needs to be clear, because he’s saying that he would force his daughter—his hypothetical daughter—to birth a rapist’s child. It’s not even a choice that we get to have. And it’s very upsetting that he thinks that he can make that choice for people in his family.” In other words, the state is already forcing women to do exactly what Lujan talked about. She cited a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that estimated that 26,000 Texas women had become pregnant due to rape in the 16 months following the ban’s enactment.

Lujan later clarified that he would only have encouraged his hypothetical daughter to have the child and was simply articulating his personal values. He has said he would work to add exceptions for rape and incest into state law if re-elected, though the legislature took no steps to do so during his first term in office.

With school vouchers hanging in the balance and a chance to send a message on abortion rights—and reverse the recent erosion of Democratic support—the race has taken on an outsized significance both inside and outside the state. Carranza recently campaigned with Democratic US Reps. Greg Casar and Joaquin Castro. Inside the cramped campaign office, where a lone “Swifties for Kamala” sign was taped above a door frame, dozens of volunteers from the Texas Organizing Project, a PAC that mobilizes voters in predominantly Black and Hispanic communities, waited for canvassing instructions. Hogg, who interrupted his brief speech to volunteers to double check with Carranza that the Lujan quote about abortion was actually real, boasted that the district was the centerpiece of his organization’s efforts in the state. Its seven-figure investment was going, in part, toward saturating the airwaves with TV ads. Some of Carranza’s spots warned about the consequences of a statewide voucher program. One ad simply played Lujan’s comments on abortion in 15-second bursts.

Democrats’ efforts in Texas have at times suffered from a bit of a false-summit problem. The big breakthrough looks so close. But adding a few million votes in a massive and ever-evolving state is hard, and the party has been burned by high expectations more than once. While there’s cautious optimism about Democrats’ post-Biden prospects this year, no one I talked to was getting out over their skis. Hogg told me he expected their investment in time and money to pay off “even if the state is not going to flip this cycle.”

“We’re just on the ground so one day Kristian could be on the forefront of that change,” he said.

Carranza said the goal now is to flip the state House by the end of the current redistricting cycle—in 2030. “They’re understanding that we have to act now before it gets worse and even if it’s going to take one year, two years, three years, five years,” she said of her conversations with voters at the door. Winning back the Southside is only the first step.