Back in June, during the CNN debate, former president Donald Trump said something very important: He promised to accept the results of the 2024 race in November if it is a “fair and legal and good election.”

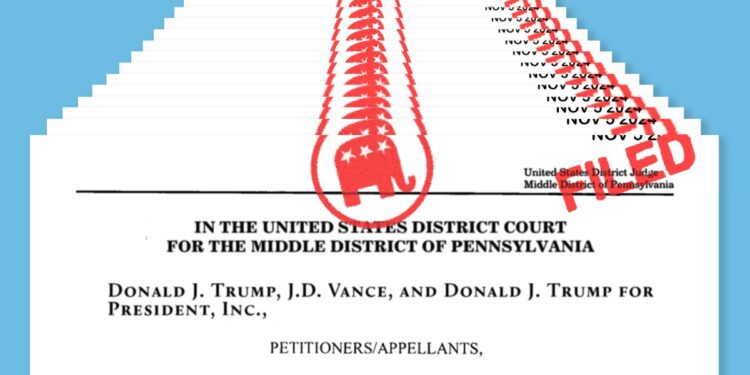

How does Trump define those terms? In 2020, he felt the election was not legitimate because he did not win. This year, he seems to have a similar calculus, saying he wants his victory to be “too big to rig.” But unlike the last presidential cycle, in which Trump’s camp filed 60-plus lawsuits asserting widespread fraud in hopes of overturning the results after the election was over, the strategy in 2024 is not haphazard and reactive. Spearheaded by the Republican National Committee, it has involved dozens of pre-election lawsuits that seem largely designed to generate voter distrust.

“It’s a little bit like throwing spaghetti at the wall—kind of like everything everywhere, all at once. Plaintiffs can file lots of similarly dubious claims in the courts and then “see if they can get anyone, any judge, to validate them after the fact.”

“At the end of the day, these lawsuits are PR campaigns in legal wrapping paper. They don’t reflect real legal concerns. They’re designed to create chaos,” says Joanna Lydgate, CEO of the pro-democracy group States United. “After the fact, when the results come in—if they don’t like the results—they have an easier time undermining them.”

As I reported in the September-October issue of Mother Jones, the RNC has laid the groundwork this year to say the election was not properly conducted by filing a deluge of lawsuits alleging illegal voting and illicit election schemes. Experts fear the RNC and far-right groups will point to their pre-election lawsuits as proof they warned the election was rigged before it even started—opening the door for even more lawsuits challenging the results that could eventually make their way to a sympathetic court.

“It’s a little bit like throwing spaghetti at the wall—kind of like everything everywhere, all at once,” says Lydgate, who formerly served as the chief deputy attorney general of Massachusetts. Plaintiffs can file lots of similarly dubious claims in the courts and then, Lydgate says, “see if they can get anyone, any judge, to validate them after the fact.”

While both political parties have filed pre- and post-election lawsuits on procedural matters over the years, many of the new claims conservatives are filing “really feel like they’re of a different ilk,” says Nora Benavidez, a civil rights and free speech attorney. Citing court cases that aim to challenge voter statuses, Benavidez says this crop of lawsuits is an attempt to “narrow opportunities for people to vote” while also insinuating that the process “needs to be shored up to fight corruption.”

Lawsuits challenging voter eligibility have repeatedly been dismissed by state and federal judges. Some of the cases about voter rolls were even launched after the statutory 90-day window before an election closes, at which point states can’t alter voter rolls. Some of the suits aren’t even seeking immediate relief, begging the question of why the lawsuits were filed at all.

Danielle Lang, senior voting rights director at Campaign Legal Center, says the agenda is obvious: “I have no doubt that those who are trying to sabotage or undermine an election might use any number of talking points to do so, including pointing it to frivolous lawsuits that they filed way too late.”

Trump’s running mate, Sen. JD Vance (R-Ohio), isn’t hiding the ball here. In an October interview with the New York Times, Vance bragged that the RNC has “filed almost 100 lawsuits at the RNC” to ensure votes are counted correctly. They define “correctly” differently than experts do.

Republicans in multiple states have tried to challenge procedures for handling ballots from military members and other voters who live abroad. In Pennsylvania, a lawsuit from six GOP members of Congress sought to impose additional checks on the eligibility and identity of overseas military members and expat citizens. (Since 2016, overseas citizens make up a bigger share of the combined cohort than overseas military members and their families; this may lead Republicans to think the overseas population favors Democrats.) A federal judge threw out the lawsuit Tuesday and criticized the congressional members for filing the suit so close to Election Day. The plaintiffs “provide no good excuse for waiting until barely a month before the election to bring this lawsuit,” the judge wrote. Other judges dismissed comparable lawsuits in Michigan and North Carolina about overseas voters within the last month.

In both Nevada and Michigan, the RNC has claimed that voting rolls are glutted with ineligible voters, who may cast ballots on Election Day that dilute the opinions of genuine voters. Those cases were dismissed in October, but a similar case challenging voter rolls was filed in Arizona by the 1789 Foundation, a right-wing group run by a lawyer known for lawsuits opposing vaccine mandates. On October 30, well after the 90-day window to remove voters passed, the group alleged Arizona is allowing up to 1.2 million ineligible voters to remain on its rolls illegally. That case is ongoing.

While unlikely to work on a broad scale, this legal onslaught can still have an impact. By filing lawsuits alleging improper voter roll maintenance or unlawful election procedures, the plaintiffs are necessitating that already-overburdened election officials spend time proving that the lawsuits are meritless.

The lawsuits also give the conspiracy of systemic election fraud a false sense of credibility. People not incredibly familiar with the legal system may be inclined to believe a legal complaint has merit just because it was filed in court, and not understand that people can claim almost anything in lawsuits.

It’s also not implausible that the plaintiffs could find a court that accepts their theories, no matter how legally flawed or politically motivated.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court suggested it is open to questionable arguments, when it overturned decisions from two lower courts and allowed Virginia’s Republican leaders to proceed (at least temporarily) with efforts to purge 1,600 people from its voter rolls. This is seemingly at odds with the 90-day window before elections in which federal law bars states from changing these lists.

The Supreme Court did not provide justification for its decision, from which the court’s three liberal justices dissented.

It’s unlikely the presidential campaigns will be fully settled when the polls close Tuesday. If the legal blitz is anything like 2020—and there’s ample evidence to suggest it may be worse—courts will get an opportunity to vote on election matters, too.