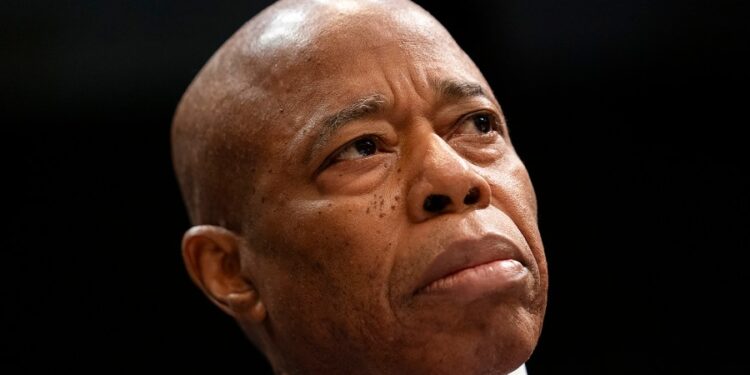

The strange official corruption case of New York City Mayor Eric Adams is about to draw to an abominable close.

The Trump Justice Department has made an unholy deal with Adams that he collaborate in its draconian crackdown on illegal immigrants, in exchange for a dismissal of the criminal corruption charges against him. Adams swore, in open court and under oath, that there was no such deal, but this was false.

Adams faced corruption charges that he accepted free hospitality and illegal indirect campaign contributions from the Turkish government in exchange for political favors. His defense was that he was borough president of Brooklyn at the time — a “but that was in another country and besides the wench is dead” defense.

The deal was so over-the-top that the Trump-appointed acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District, Danielle Sassoon, resigned in protest along with five other Justice Department lawyers.

Sassoon, a former clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia, noted in her resignation letter that “Adams’s attorneys repeatedly urged what amounted to a quid pro quo, indicating that Adams would be able to assist with the department’s enforcement priorities only if the indictment were dismissed.” She added that Trump’s appointed Deputy Attorney General, Emil Bove, demanded all notes taken at this meeting.

Trump Border Czar Tom Homan, appearing alongside Adams on “Fox and Friends,” obtusely spelled out the quid pro quo: “If he doesn’t come through, I’ll be back in New York City, and we won’t be sitting on the couch, I’ll be in his office, up his butt, saying ‘Where the hell is the agreement we came to?’” To which outrageous statement Adams laughed nervously. Was Homan kidding? I don’t think so.

The Justice Department wanted a dismissal under Criminal Rule 48, but with an odd fillip appearing nowhere in the rule, a dismissal “without prejudice.” This means the case could be resurrected in the future. This transparent ploy would mean that the administration wants to hold Adams’s feet to the fire, retaining the ability to prosecute him later on the charges if he steps out of line.

The motion for dismissal was so bizarre that District Judge Dale Ho appointed a conservative lawyer — Paul Clement, the highly respected solicitor general in the George W. Bush administration — to “to present arguments on the government’s motion to dismiss.”

“Normally, courts are aided in their decision-making through our system of adversarial testing, which can be particularly helpful in cases presenting unusual fact patterns or in cases of great public importance,” the Judge Ho wrote.

The adversarial system is the crown jewel of the common law we got from the British. And the appointment of an outside lawyer may be necessary when both sides seek dismissal and there is no one on hand to represent the public.

Clement’s conclusion was to recommend the dismissal of the entire case “with prejudice” so that it would never again see the light of day. Clement contended that the provision in the rules requiring leave of court for such a dismissal is for the protection of the defendant, and the court should not permit the defendant to live under a looming Sword of Damocles.

A court’s discretion in a Rule 48 motion is normally quite circumscribed, but it has plenty of discretion to deny it on these facts or at least to hold a hearing.

The court may want to scrutinize the government’s motive, let alone the Justice Department’s legal reasoning in seeking dismissal. Here, the facts were particularly glaring. The department conceded that it took its decision not to prosecute “without assessing the strength of the evidence or the legal theories on which the case is based.” Really?

Rule 48 permits courts faced with dismissal motions to consider the public interest “in the fair administration of criminal justice and the need to preserve the integrity of the courts.” One court held that even when the defendant consents to dismiss, the trial court may deny the motion in extremely limited circumstances when the prosecutor’s actions indicate a “betrayal of the public interest.”

“The judge should be satisfied that the agreement adequately protects the public interest” and “may withhold approval if he finds that the prosecutor committed ‘such a departure from sound prosecutorial principle as to [constitute] an abuse of prosecutorial discretion,” an appellate court said.

Judge Ho has yet to rule on the government’s motion, but the smart money is that he is all but certain to dismiss the case. Criminal cases rest on a three-legged stool involving the branches of government: Congress makes the law, the executive branch prosecutes and the judiciary presides over a fair trial in accordance with the law. But it is only the executive branch that can initiate a criminal prosecution, and only the executive branch that can end one, either by moving the court under Rule 48 or by use of the pardon power.

It is virtually unheard of for the judiciary to order the executive to prosecute a case when it is unwilling to do so, and it is only in the rarest of instances involving contempt of court that the judge can appoint an independent counsel to prosecute a criminal case.

Interestingly, nowhere in Clement’s 26-page “Brief of Appointed Amicus Curiae” does he cite the case involving Gen. Michael Flynn from Trump’s first term. In May 2020, when Justice sought to dismiss the Flynn case using Rule 48 against the Trump crony who had pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI, the judge in Washington appointed an outside lawyer, retired District Judge John Gleesson, to assist the court.

Gleesson found the behavior of the Justice Department in seeking to dismiss a criminal case after the defendant pleaded guilty a “gross abuse of power.” He concluded in the strongest language that the “facts reveal an unconvincing effort to disguise as legitimate a decision to dismiss that is based solely on the fact that Flynn is a political ally of President Trump.”

Clement never went there in the Adams case.

Our law is based on precedents, and the Adams case presents a particularly bad one. If the case is dismissed, it surely means that any public official justly accused of corruption can wriggle out merely by supporting a president’s political agenda.

The case is truly one for the books. This has never been the way our laws have been enforced in American history. It is a true miscarriage of justice.

James D. Zirin, author and legal analyst, is a former federal prosecutor in New York’s Southern District. He is also the host of the public television talk show and podcast Conversations with Jim Zirin.