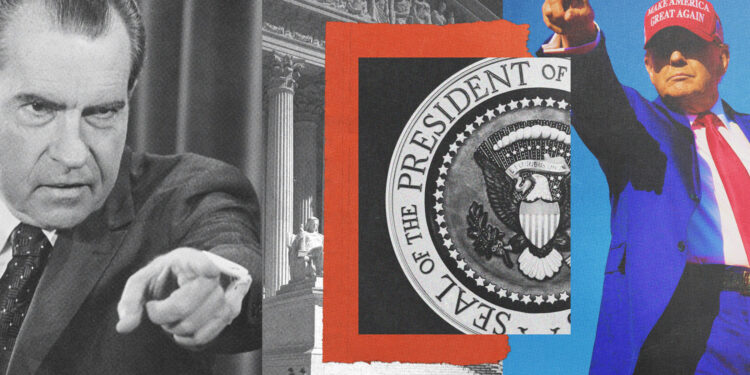

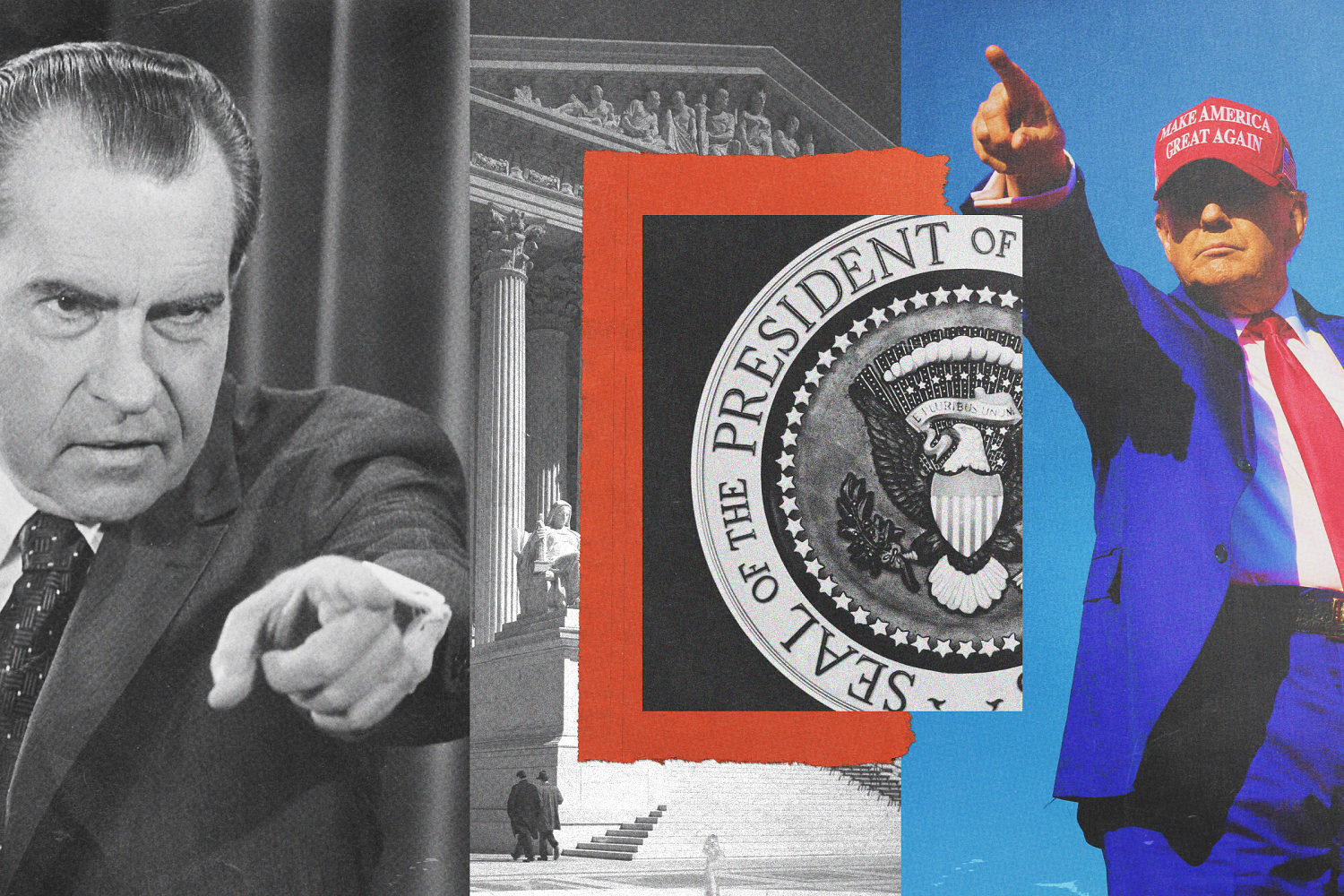

WASHINGTON — When President Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon in 1974 it was under the assumption that his predecessor could have been prosecuted for his efforts to impede the investigation into the Watergate scandal.

But under the new rule implemented by the Supreme Court on Monday that partially immunized Donald Trump in his election interference case, there may not have been any need for such a pardon.

“Richard Nixon would have had a pass,” John Dean, Nixon’s White House Counsel, said on a call with reporters Monday.

The Supreme Court said core presidential functions such as communicating with other officials are absolutely immune from prosecution. And other acts that may straddle the line are presumptively immune, meaning a defendant can assume they are immune unless a prosecutor can prove otherwise.

Future presidents, unlike Nixon, will enter office knowing they can insulate themselves from prosecution as long as their allegedly illegal acts can be defended as exercises of a bedrock presidential power. Presidents who commit criminal acts can still face removal from office via the impeachment process.

Under the new test, “virtually all of the evidence” against Nixon in relation to the cover-up of the break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices in 1972 could have been off-limits, Dean added.

Among the conduct at issue would have been Nixon’s attempts to enlist the CIA in the scheme, including asking it to stop the FBI investigation into the break-in. Dean himself pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice for his role in the scandal.

Nixon was pardoned after he resigned as president on the verge of being impeached.

The Watergate comparison illustrates how Monday’s ruling has broad repercussions that affect more than just whether Trump’s prosecution will ever go to trial.

It was a theme seized upon by the court’s three liberal justices, who vociferously objected to the ruling.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in a dissenting opinion that the ruling constitutes a “five-alarm fire that threatens to consume democratic self-governance.”

Although Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote the majority opinion, downplayed the impact, chiding Jackson and her liberal colleagues for the “tone of chilling doom” they adopted, legal experts expressed concern about the practical repercussions the decision could have.

Some returned to a hypothetical question asked during the Trump appeal about whether a president could order SEAL Team 6 to assassinate a political rival. Lower courts had ruled that such conduct could clearly be prosecuted.

But the Supreme Court ruling seems to suggest it would be subject to immunity, legal experts said.

“Under this opinion, I think that’s actually now true,” said Randall Eliason, a former prosecutor who teaches at the George Washington University Law School. “Commanding the military is a core presidential function, so that order would be entitled to absolute immunity.”

Matthew Seligman, a lawyer closely following the Trump case who filed a brief backing prosecutors, said the ruling is “exceptionally dangerous” because of the message it sends to future presidents.

“The lesson for future autocrats is next time make sure you abuse the official levers of power” to ensure your conduct will be seen as a presidential duty and therefore subject to immunity, he said.

Liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor touched upon that theme in her own dissenting opinion, saying the SEAL Team 6 hypothetical, an attempted coup or taking a bribe in exchange for a pardon would all be immunized.

“Even if these nightmare scenarios never play out, and I pray they never do, the damage has been done,” she wrote.

In his opinion, Roberts rejected the dissenting justices’ “fear mongering on the basis of extreme hypotheticals,” saying the alternative — a president “unable to boldly and fearlessly carry out his duties” — would be worse.

As conservative Justice Samuel Alito, who was in the majority, pointed out during oral argument in response to the SEAL Team 6 scenario, members of the military are bound not to obey unlawful orders.

John Malcolm, vice president of the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Constitutional Government, praised the ruling, saying presidents should not be second-guessed for making snap decisions under pressure.

“I don’t think that, for the most part, we elect mobsters and gang members as presidents,” he added. “Most of them are honorable people.”