Shortly before Stateville Correctional Center opened in 1925, officials laid out their ambitious goals for the prison: “Warden John J. Whitman in his dedication address declared the function of the model prison would be the reformation of men who had run afoul of the law not merely a place of punishment,” the Tribune reported on Dec. 7, 1924.

Seven years later, amid criticism in one corner that inmates were being pampered, and in another that conditions were unfair, another warden reported that to fulfill Whitman’s lofty promise he had to steer a course between equally perilous ways of dealing with inmates.

“If we are too good to them, they could trample upon us. If we are too harsh with them they might riot or mutiny, and we’d have to kill them,” Maj. Henry C. Hill told the Tribune.

A magnet for controversy from the start, the aging and decrepit prison near Joliet is set to be demolished by the state of Illinois, which plans to rebuild a new facility on the site using more modern concepts of prison architecture.

Stateville’s famous roundhouses were once seen as just that, state of the art facilities based on ideas sketched out by Jeremy Bentham, an 18th and early 19th century English philosopher and social reformer, in his essay, “Panopticon, or The Inspection House.”

“The Building circular,” Bentham wrote, “The Prisoners in their Cells, occupying the Circumference — The Officers, the Center. By Blinds, and other contrivances, the inspectors concealed from the observation of the Prisoners, hence the sentiment of a sort of invisible omnipresence.”

Almost a century after Bentham’s death, sociologists and legal authorities were still wrestling with the idea of whether a prison rehabilitates criminals? The question was put to a test by the construction of Stateville.

Stateville’s F House, shuttered in 2016, was the last standing of the prison’s original four roundhouses. They were built with a tower staffed by armed guards at the center of an atrium and surrounded by inmates’ cells. Guards had an uninterrupted view of whatever mischief inmates might be up to.

Some inmates apparently took that as a challenge to their creativity.

In 1971, an inmate convicted of murder and two convicted of armed robbery escaped. “The three apparently donned civilian attire in a room near the prison hospital and walked through the front gates with a group of 200 people visiting the prison to view an art fair by convicts,” the Tribune reported, under a sub-headline: “Second Break Out This Year.”

The man convicted of murder had made four escape attempts from Cook County Jail.

Stateville was also not immune to inmate uprisings and general mayhem.

In 1931, the Tribune reported that half of the 20-member prison band at Stateville had wanted to initiate a general riot, while the other half was opposed.

“Closing in on each other, the two factions used chairs and musical instruments to beat each other until guards overpowered them and placed the whole crew in solitary confinement,” the Tribune story said.

In 1996, Attorney General Jim Ryan ordered an investigation after WBBM-Ch. 2 aired a 1988 videotape showing mass murderer Richard Speck claiming to have sex with another inmate and access to drugs while incarcerated in Stateville. On another tape, Larry Hoover bragged about being able to head his street gang while in Stateville.

Not too many years after the prison opened, a blue-ribbon committee said chaos reigned in Stateville. In an effort to remedy that, Joseph Ragen, who had earned a reputation as a tough disciplinarian while warden of the state prison in Menard, was appointed warden in 1936. Before long, Ragen could brag of having made it “the tightest run prison in the United States.”

Ragen’s self-evaluation was confirmed by Nathan Leopold, the infamous thrill killer of the “Crime of the Century.” Confined there, Leopold said Stateville was “so tight it cracks.”

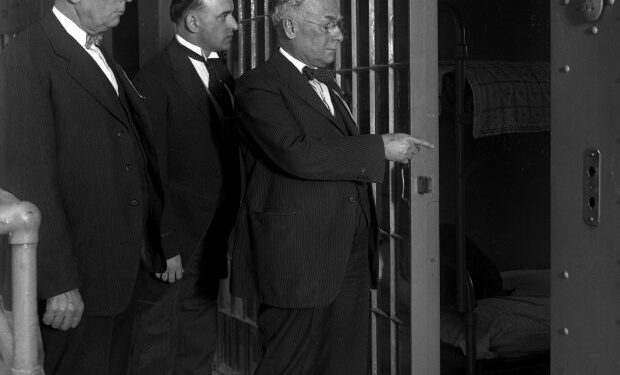

Ragen’s theory of imprisonment depended on making inmates more afraid of him than he was of them. Leaving the guards behind, he made his morning rounds of the cell blocks accompanied by two dogs. Inmates who bucked him learned why Ragen was proud of being said to rule with an “iron hand.” Warden Joseph Ragen shows how a hammer can be hidden in a mattress at Stateville Prison on Jan. 3, 1937. (Mann/Chicago Herald and Examiner)[/caption]

Warden Joseph Ragen shows how a hammer can be hidden in a mattress at Stateville Prison on Jan. 3, 1937. (Mann/Chicago Herald and Examiner)[/caption]

“During his 25-year term as warden, there were no riots, not a single escape from behind the walls, and only two guards and three inmates were killed,” James B. Jacobs wrote in his book, “Stateville, the Prison in Mass society,” which the Tribune excepted on July 30, 1978.

While Stateville was a living hell for those incarcerated there, it was catnip to Hollywood directors, several of whom used the prison as a location for their films. In 1987, director John Hancock had Stateville’s inmates play the inmates in his film “Weeds”. Two hundred fifty of them got $20 a day for the gig, and one of them, Daniel F. Duane, showed a gift for improvisation.

Serving 15 years for armed robbery, Duane escaped aboard a truck carrying the film’s crew and equipment after telling the driver he was a prison employee and wanted a lift to the parking lot. Three days later, he was apprehended in Rapid City, South Dakota.

A list of Stateville’s alumni would tempt scriptwriters to white out a dull paragraph with a sonorously intoned voice-over:

Floyd Cummings: Served 12 years for murder. Then embarked on a boxing career and fought ex-heavyweight champion Joe Frazier to a draw.

William Heirens: A serial murderer known as “The Lipstick Killer”

Roger Touhy: Bootlegger and alleged kidnaper of a rival mobster, John “Jake the Barber” Factor, whose half-brother, Max Factor, was the cosmetics mogul.

The electric chair was first used at Stateville in 1949, and the prison often drew crowds when the death penalty was to be executed.

By the time John Wayne Gacy was put to death, the electric chair had been replaced by lethal injection. A crowd of 1,000 stood in front of Stateville on May 10, 1994. Some considered the death penalty barbaric, no matter the means. Others chanted “Kill the Clown!” Gacy had entertained kids costumed as a clown and killed more than 30 young men.

Gary Gauger spent almost three years on death row after was wrongly convicted of charges that he murdered his parents. In 2002, he was among those who marched outside Stateville in support of abolishing capital punishment in Illinois.

“Look at it,” Gauger said to reporters gathered outside the prison. “That place is really Gothic, like something out of a Batman movie. Unreal.”

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at [email protected] and [email protected]. Don’t forget to sign up to receive the weekly Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter at chicagotribune.com/newsletters for more photos and stories from the Tribune’s archives.