Few prehistoric monsters capture the imagination quite like the megalodon.

From natural history museums to the silver screen, this colossal shark, which went extinct over three million years ago, has been depicted as one of the most terrifying and ferocious predators to ever roam the planet.

However, new research from the University of California, Riverside, published Monday in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica, could forever change our perception of “The Meg.”

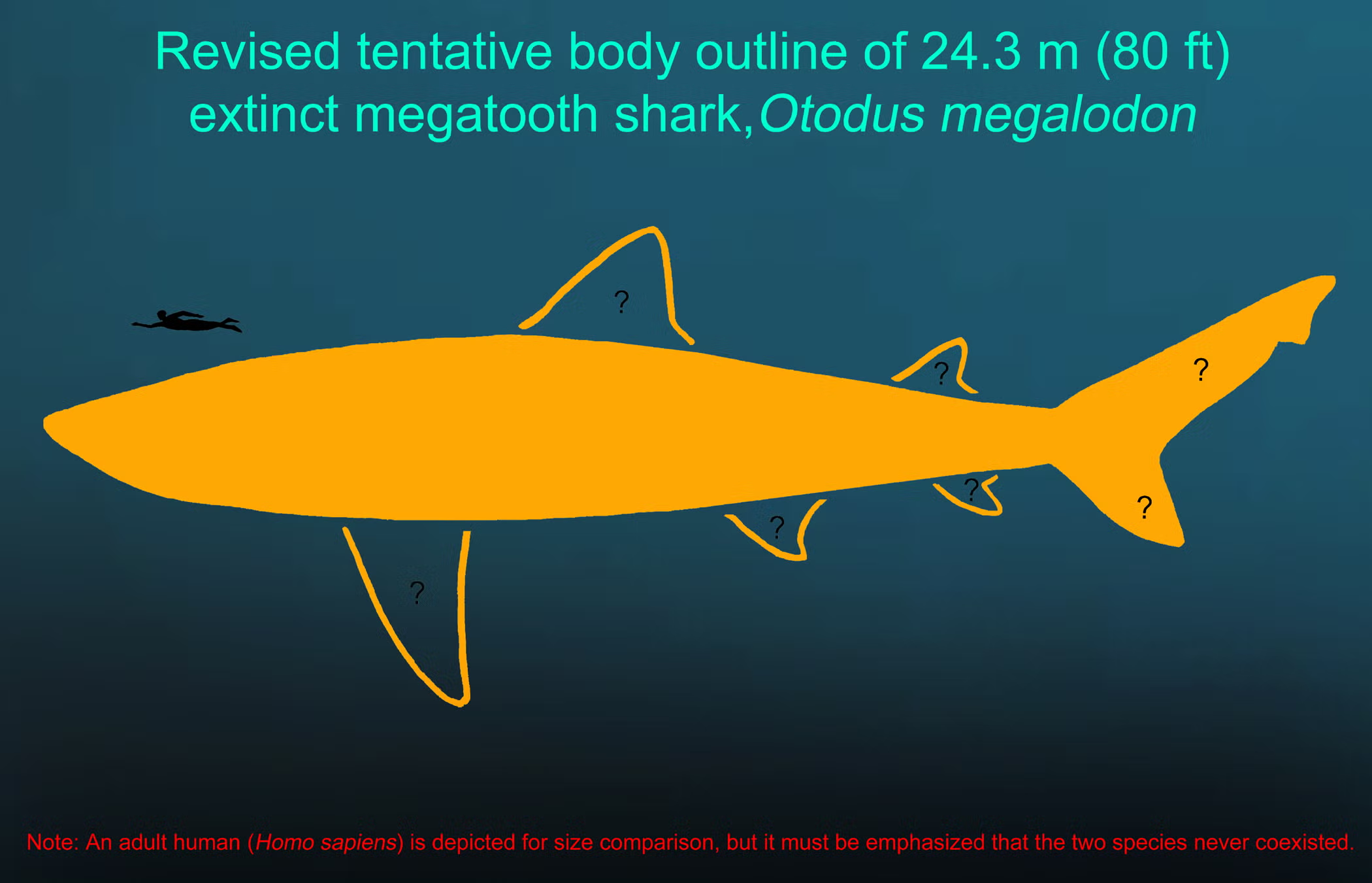

Until now, the megalodon has been envisioned as a much larger version of the great white shark with a similarly chunky body type. Typical methods of estimating its shape and size have relied on teeth and limited vertebral specimens since no complete adult skeletons have been found.

“By examining megalodon’s vertebral column and comparing it to over 100 species of living and extinct sharks, (researchers) determined a more accurate proportion for the head, body, and tail,” UCR stated.

Research now suggests that the megalodon more closely resembled a lemon shark with a much longer body—perhaps similar to a large whale—measuring about 80 feet in length and weighing 94 tons. Its slender body was designed for energy-efficient cruising rather than short, high-speed attacks.

“You lead with your head when you swim because it’s more efficient than leading with your stomach,” said Tim Higham, a UCR biologist who contributed insights to the study. “Similarly, evolution often moves toward efficiency.”

For comparison, great white sharks can grow up to 20 feet long, however its body is better suited for bursts of speed.

Researchers also believe that a newborn megalodon could have been nearly 13 feet long, roughly the size of an adult great white shark.

“It is entirely possible that megalodon pups were already taking down marine mammals shortly after being born,” said Phillip Sternes, a shark biologist at UCR.

UCR hopes the study offers better insight into why only certain animals, beyond the megalodon, can evolve to massive sizes.