Riccardo Bosio made local headlines in 2016 when, frustrated by diners who reserved coveted spots to his Opera Night dinners only to bail at the last minute, he decided to assess a penalty on no-show customers.

Eight years later, the fees are becoming increasingly commonplace as restaurateurs look for ways to discourage last-minute cancellations from a dining public that, by many accounts, has grown flakier since the coronavirus pandemic.

“Now everyone is following suit,” Bosio, the owner of the Mount Vernon Italian restaurant Sotto Sopra, said this week.

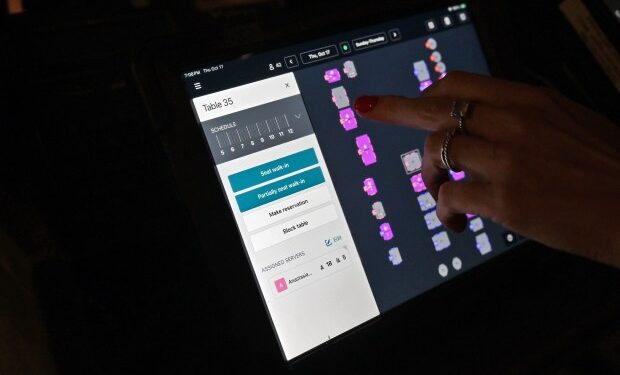

A cursory look at booking platforms like Resy and OpenTable shows some of Baltimore’s top restaurants have cancellation fees. Intimate dining rooms like Woodberry Tavern and Le Comptoir du Vin ask for advance notice of a canceled reservation in order to avoid the charge. So do popular spots such as The Urban Oyster, Thames Street Oyster House and Papi Cuisine.

OpenTable data from 2021 showed that more than a quarter — 28% — of Americans admitted to not showing up for a reservation in the past year. Though some of those seats can be filled by walk-in customers, restaurant owners say no-shows gnaw at their bottom line and make it harder to plan food orders and staff schedules. Tipped workers like servers and bartenders suffer, too, when they are sent home early or make less than anticipated on what was supposed to be a busy night.

“For me, it was a cultural shock,” said Bosio, who opened his upscale Italian restaurant in 1996. “Restaurants in the past 5 years have taken a ton of cancellations. If you see a shift like this in an industry, you see there is a major problem. The technology makes it a lot easier to cancel without accountability.”

Though a few balked at his decision to charge $50 per person for canceled Opera Night reservations and $30 a head for parties of six people or more who cancel less than 24 hours in advance, most of his customers were supportive.

“It’s just to make you remember,” Bosio said. Since implementing the fees, he added, “it’s not such a problem anymore.”

Just like airlines and hotels, restaurants have what’s called “fixed capacity:” There are only so many tables in a dining room, rooms in a hotel and seats on an airplane, and if they’re not filled on a given night or during a particular flight, a business can’t recuperate that lost revenue.

That’s why hotels and airlines have cancellation fees — and why airlines will sometimes overbook a flight, anticipating some cancellations. But diners don’t think of restaurants the same way, said Julaine Rigg, director of Morgan State University’s hospitality management program and associate professor.

“Most people are resistant to change,” Rigg said, but “at the end of the day, a table of 10 people not showing up can actually be the difference between a restaurant profit or loss that night. You can understand why restaurants are trying to fight back.”

Rigg said at Michelin-starred and other high-end restaurants, where a meal can cost hundreds of dollars, steep cancellation penalties have long been an accepted practice. In Baltimore, fees for a missed reservation are more modest, ranging from $10 to $50 per guest. Grace periods also vary by restaurant, with some asking for only an hour’s notice to avoid a charge, while others require a full 24 hours. Some dining spots ask for a deposit, rather than a fee, that is later deducted from the dinner bill.

Tony Foreman, who runs the Baltimore-based Foreman Wolf restaurant group with James Beard-nominated chef Cindy Wolf, doesn’t charge cancellation fees at most of the hospitality company’s restaurants, which include Petit Louis Bistro, Cinghiale, Johnny’s and The Milton Inn. But customers who make a reservation at Charleston, Foreman Wolf’s acclaimed Harbor East dining room, are notified that they might be on the hook for a $50-a-person fee if they don’t show up for their dinner.

“It’s about the decision-making of the diner,” Foreman said of the choice to charge a cancellation fee at Charleston but not the other restaurants. “For something like a dinner experience at Charleston, people don’t typically find that last minute — and because of that, those are pretty irreplaceable commitments. If we don’t replace that commitment, we tend to hold people to it, at least in some measure.”

Using that same reasoning, Foreman said he implements last-minute cancellation fees at his other restaurants for special occasions like holiday meals, when it’s unlikely that walk-in diners will fill abandoned seats. “Thanksgiving is different from a Wednesday night in September,” he said.

Still, Foreman says he doesn’t often have to charge the fees — and the restaurant will waive them when there are extenuating circumstances. “We don’t get many capricious cancellations at Charleston,” he said. “People plan and look forward to it.”

Though attitudes seem to be changing, restaurant strategist Martha Lucius thinks the dining industry has previously been hesitant to charge no-show penalties because they seem to run counter to the very notion of hospitality, where there is often a “customer is always right” mentality.

“It’s part of hospitality to not have punitive costs,” Lucius said. “Restaurants don’t want to charge this; they’re trying to figure out how not to, but if they’re doing it, they’re doing it for a doggone good reason.”

Behind the scenes, she said, restaurants are paying hefty sums for booking platforms; a subscription to OpenTable, for instance, can cost a larger establishment $2,000 a month. “There’s two sides of the coin: one is the reservation being put in, and then there is the cost of a reservation system,” Lucius said. “In Baltimore, I feel the restaurant owners are being hand-tied by the apps that charge them a chunk of money.”

Some restaurants in nearby Washington, D.C., are giving up on reservations altogether and accepting walk-in customers only to avoid the headache of no-shows and platform fees, Lucius added.

But for those who charge cancellation fees, communication and flexibility are key to helping them gain wider acceptance, Rigg said. In February, a Boston fine-dining spot called Table went viral after chef and owner Jen Royle got into an online spat with a customer who disputed a $250 charge for a missed reservation. Royle berated the customer for “screwing over” her restaurant and staff; the customer countered that he had to cancel because he was hospitalized. The outcry forced her to temporarily lock down her personal and professional social media pages.

“The more clarity that is provided by the restaurant, I think the more understanding we as consumers will be,” Rigg said.

“Nobody likes to get stood up,” she added.

Have a news tip? Contact Amanda Yeager at [email protected], 443-790-1738 or @amandacyeager on X.