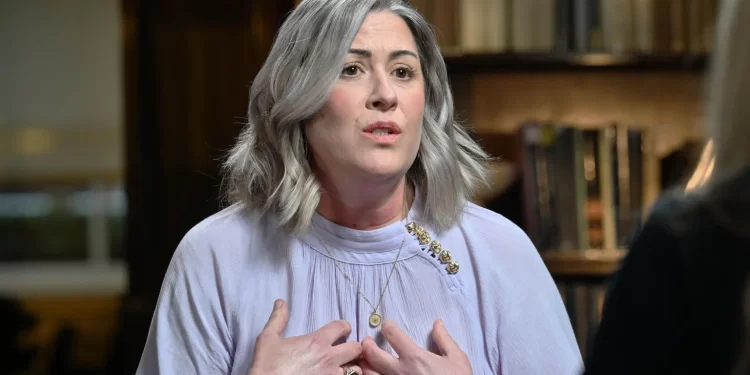

Caroline Darian: “He should die in prison. He is a dangerous man.”

Warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual abuse

It was 20:25 on a Monday evening in November 2020 when Caroline Darian got the call that changed everything.

On the other end of the phone was her mother, Gisèle Pelicot.

“She announced to me that she discovered that morning that [my father] Dominique had been drugging her for about 10 years so that different men could rape her,” Darian recalls in an exclusive interview with BBC Radio 4’s Today programme’s Emma Barnett.

“At that moment, I lost what was a normal life,” says Darian, now 46.

“I remember I shouted, I cried, I even insulted him,” she says. “It was like an earthquake. A tsunami.”

Dominique Pelicot was sentenced to 20 years in jail at the end of a historic three-and-a-half month trial in December.

More than four years later, Darian says that her father “should die in prison”.

Fifty men who Dominique Pelicot recruited online to come rape and sexually assault his unconscious wife Gisèle were also sent to jail.

He was caught by police after upskirting in a supermarket, leading investigators to look closer at him. On this seemingly innocuous retired grandfather’s laptop and phones, they found thousands of videos and photos of his wife Gisèle, clearly unconscious, being raped by strangers.

On top of pushing issues of rape and gender violence into the spotlight, the trial also highlighted the little-known issue of chemical submission – drug-facilitated assault.

Caroline Darian has made it her life’s struggle to fight chemical submission, which is thought to be under-reported as the majority of victims don’t have any recollection of the assaults and may not even realise they were drugged.

Jeff Overs/BBC

Jeff Overs/BBCDarian wants abused women’s voices to be heard

In the days that followed Gisèle’s fateful phone call, Darian and her brothers, Florian and David, travelled to the south of France where their parents had been living to support their mother as she absorbed the news that – as Darian now puts it – her husband was “one of the worst sexual predators of the last 20 or 30 years”.

Soon afterwards, Darian herself was called in by police – and her world shattered again.

She was shown two photos they found on her father’s laptop. They showed an unconscious woman lying on a bed, wearing only a T-shirt and underwear.

At first, she couldn’t tell the woman was her. “I lived a dissociation effect. I had difficulties recognising myself from the start,” she says.

“Then the police officer said: ‘Look, you have the same brown mark on your cheek… it’s you.’ I looked at those two photos differently then… I was laying on my left side like my mother, in all her pictures.”

Darian says she is convinced her father abused and raped her too – something he has always denied, although he has offered conflicting explanations for the photos.

“I know that he drugged me, probably for sexual abuse. But I don’t have any evidence,” she says.

Unlike her mother’s case, there is no proof of what Pelicot may have done to Darian.

“And that’s the case for how many victims? They are not believed because there’s no evidence. They’re not listened to, not supported,” she says.

Soon after her father’s crimes came to light, Darian wrote a book.

I’ll Never Call Him Dad Again explores her family’s trauma.

It also delves deeper into the issue of chemical submission, in which the drugs typically used “come from the family’s medicine cabinet”.

“Painkillers, sedatives. It’s medication,” Darian says. As is the case for almost half of victims of chemical submission, she knew her abuser: the danger, she says, “is coming from the inside.”

She says that in the midst of the trauma of finding out she had been raped more than 200 times by different people, her mother Gisèle found it difficult to accept that her husband may have also assaulted their daughter.

“For a mum it’s difficult to integrate that all in one go,” she says.

Yet when Gisèle decided to open up the trial to the public and the media so as to expose what had been done to her by her husband and dozens of men, mother and daughter were in agreement: “I knew we went through something… horrible, but that we had to go through it with dignity and strength.”

Reuters

ReutersNow, Darian needs to understand how to live knowing she is the daughter of both the torturer and the victim – something she calls “a terrible burden”.

She is now unable to think back to her childhood with the man she calls Dominique, only occasionally slipping back into the habit of referring to him as her father.

“When I look back I don’t really remember the father that I thought he was. I look straight to the criminal, the sexual criminal he is,” she says.

“But I have his DNA and the main reason why I am so engaged for invisible victims is also for me a way to put a real distance with this guy,” she tells Emma Barnett. “I am totally different from Dominique.”

Darian adds she doesn’t know whether her father was a “monster,” as some have called him. “He knew perfectly well what he did, and he’s not sick,” she says.

“He is a dangerous man. There is no way he can get out. No way.”

It will be years before Dominique Pelicot, 72, is eligible for parole, so it is possible he will never see his family again.

Meanwhile, the Pelicots are rebuilding themselves. Gisèle, Darian said, was exhausted from the trial, but also “recovering… She is doing well”.

Reuters

ReutersAs for Darian, the only question she is interested in now is to raise awareness of chemical submission – and to better educate children on sexual abuse.

She derives strength from her husband, her brothers and her 10-year-old – her “lovely son”, she says with a smile, her voice full of affection.

The events that were unleashed on that November day made her who she is today, Darian says.

Now, this woman whose life was wrecked by a tsunami on a November night is trying to only look ahead.

‘You can watch the full interview ‘Pelicot trial – The daughter’s story’ – on Monday at 7pm on BBC 2 or on the iPlayer. If you have been affected by some of the issues raised in this film, details of help and support are available at bbc.co.uk/actionline’.