As part of the series “Culture of Corruption,” the Tribune has compiled a list of roughly 200 convicted, indicted or generally notorious public officials from Illinois’ long and infamous political history. We’re calling it “The Dishonor Roll.” On this page you can read about examples from the judicial branch of government.

This list isn’t meant to be exhaustive, and the Tribune will be updating it as warranted. “The Dishonor Roll” draws heavily from the vast archives of the Tribune, including photography and pages from the newspaper on the days these public officials made headlines.

Read more of “The Dishonor Roll” below:

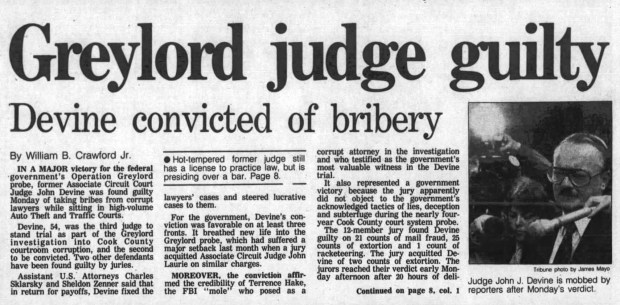

John J. Devine

Judge John J. Devine died of cancer in federal prison while serving a 15-year sentence related to Operation Greylord, the federal corruption investigation. He was convicted of taking payoffs from corrupt lawyers while he was a judge in Auto Theft Court and Traffic Court. A jury found Devine, who had pleaded innocent in December 1983, guilty of 25 counts of extortion and one count of racketeering.

A secret Chicago Bar Association report sent out in June 1, 1983, recommended Devine and eight other sitting associate judges be removed. Three weeks later, his colleagues voted him and four other justices off the bench — the first time that had happened in Cook County. He was indicted by a federal grand jury for the first time on Dec. 14, 1983, with another Cook County Circuit Court judge, a former judge, three attorneys, a court clerk, a former bailiff and a police officer.

Paul Foxgrover

A longtime Cook County associate judge, Paul Foxgrover was once called by a prosecutor a “criminal in robes.” He was sentenced in 1992 to six years in state prison after pleading guilty to stealing fines he imposed on defendants who appeared in his courtroom. He was the first Cook County judge to be sentenced to a state prison term after being part of a scheme to pocket more than $50,000 in court fines.

Daniel Glecier

With a six-year term and a $50,000 fine, former Associate Judge Daniel Glecier received one of the lightest sentences for a Cook County judge in Operation Greylord. He was convicted of paying bribes as a lawyer and later taking them as a judge while sitting in the south suburban 5th Municipal District. Glecier was stripped of his judgeship following his sentencing. At the time, he became the 14th sitting or former judge convicted on charges resulting from the Greylord investigation. Two co-defendants in his case, Judge Francis Maher and attorney David Dineff, were acquitted.

James Heiple

Illinois Supreme Court Chief Justice James Heiple told the Tribune he knocked out a fellow law student’s two front teeth in what he called “a very satisfying punch.” Heiple — deemed “imperious,” “arrogant” and discourteous to colleagues — became the subject of the state’s first formal impeachment proceedings in more than 150 years, but a House panel voted 8-2 against impeachment. Before the vote, Heiple pleaded guilty to two petty offenses then was censured for misconduct by the Illinois Courts Commission over his actions during a series of traffic stops in which he was accused of disobeying police and abusing his position to avoid speeding tickets.

Heiple, who wrote the opinion in the “Baby Richard” case, stepped down as chief justice two days after he was censured for his behavior during the traffic stops, but he remained on the bench. He retired in 2000.

Martin Hogan

A federal judge contended it “burned my gut” to hear testimony in an Operation Greylord case that former Associate Judge Martin Hogan stood as his own lookout while a bribe was passed. “I had to hang my head when I heard that testimony,” said U.S. District Judge James Holderman as he sentenced Hogan to 10 years in federal prison.

A prosecutor assailed Hogan for testifying he did not take any bribes — especially after it was revealed Hogan used $9,000 in bribe money to pay for the upkeep on his 35-foot yacht.

Reginald Holzer

Originally sentenced in Operation Greylord to 18 years in prison, Holzer was re-sentenced to 13 years when part of his conviction was overturned. He originally was convicted on mail fraud, racketeering and extortion charges, but an appeals court vacated the mail fraud and racketeering convictions once the U.S. Supreme Court narrowed the interpretation of the mail fraud statute. The 18-year sentence had been the longest term imposed in the Greylord investigation.

Holzer was accused of using his position to extract more than $200,000 in personal loans from lawyers and others who appeared before him. During his trial, Holzer did not deny making the loan transactions but denied the transactions were illegal. The loans were engineered routinely by others, Holzer said, who knew the judge was financially strapped. He testified that in 1984, the interest payments on his loans exceeded his $60,000-a-year salary. Holzer, who had handed out some of the harshest sentences for felons convicted of violent crimes while he was on the bench, was released from prison in 1990 and died in 1992.

Ray Klingbiel

A special commission appointed by the Illinois Supreme Court concluded that Chief Justice Roy Solfisburg Jr. and Justice Ray Klingbiel — who delivered the court’s opinion in November 1968 confirming Richard Speck’s conviction was fair — committed misconduct by participating in a case in which they had a financial stake. The investigative panel said the justices committed “positive acts of impropriety” by accepting gifts from Theodore J. Isaacs, a founder of the Civic Center bank, while they considered a case involving Isaacs in the Supreme Court. Klingbiel testified before the commission that he received $2,000 worth of stock in the bank as a campaign contribution, but he didn’t know that he received it while Isaacs’ case was before him for judgment.

The commission report said it didn’t believe Solfisburg and Klingbiel were truthful in testifying they didn’t realize he was “one of the influential” organizers of the bank at the time they ruled in Isaac’s favor in the case. Though the justices denied wrongdoing, they both stepped down.

Richard LeFevour

Circuit Court Judge Richard LeFevour was sentenced to 12 years in prison after he was convicted in 1985 of accepting $400,000 in bribes to fix drunken driving cases and overdue parking tickets.

Before he became the highest-ranking judge charged in Operation Greylord, Richard LeFevour had been chief judge of Traffic Court (at the time the nation’s largest court of its kind) from 1972 to 1981, then chief judge of the 1st Municipal District.

His cousin, retired Chicago police officer James LeFevour, served as not only his court aide but also as a “bagman” who delivered “hundreds” of payments of $100 each to fix drunken driving cases or assign them to judges who would. When a television reporter aired allegations that tickets were being fixed in return for payoffs, Richard LeFevour ordered the documents destroyed.

In all, Richard LeFevour was found guilty of 53 counts of mail fraud, one count of racketeering and five counts of income tax fraud. The sentencing automatically stripped him of his position.

Thomas J. Maloney

Thomas J. Maloney, a former boxer, was believed to have sentenced more defendants to Death Row than just about any other Criminal Court judge. He also holds the notorious distinction of being the first Cook County judge convicted of rigging murder cases for money.

Maloney was indicted on charges that he fixed three murder trials for thousands of dollars in bribes: the 1981 murder trial of three New York gang members cleared of killing a rival in Chicago’s Chinatown, the 1986 trial of a leader of the notorious El Rukn street gang who was charged with a double murder, and a case where Maloney found an accused murderer guilty of a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced him to nine years. In the El Rukn case, Maloney apparently suspected the FBI was onto the fix and personally handed the cash back to a corrupt attorney before convicting two gang members.

He was sentenced in 1993 to 15 years and nine months in prison. Maloney died in 2008.

John McCollom

Former Cook County Circuit Judge John McCollom received an 11-year sentence in Operation Greylord after he pleaded guilty to charges he accepted bribes to fix drunken-driving cases while assigned to Traffic Court. A prosecutor said evidence showed McCollom accepted nearly $300,000 in bribes during the decade he sat on the bench and the former judge refused to cooperate in the probe.

Sheldon Zenner, then an assistant U.S. attorney, contended the people who suffered from McCollom’s crimes “were those who did not pay the bribes — the poor, the powerless, the pitiful, those without clout.” McCollom abruptly pleaded guilty midway through his trial on charges of racketeering, mail fraud and income tax fraud, admitting to taking bribes from lawyers and police officers to fix hundreds of cases over eight years in traffic court.

John J. McDonnell

Judge John J. McDonnell, who had been on the bench since 1971 and heard cases at Traffic Court and branch courts, was sentenced in 1989 to six years in prison. Prior to that, the only previous blot on McDonnell’s record was a suspension for threatening a couple with a handgun that he claimed was a cigar. The charges against McDonnell represented the 15th and last major judicial case related to the decade-long Operation Greylord investigation.

McDonnell had been charged with one count of racketeering, two counts of extortion, one count of obstruction of justice and three counts of tax evasion. He pleaded guilty to extortion for taking payments of $50 to $700 from attorney Karl Canavan between 1980 and 1983 for referring clients to Canavan while McDonnell was assigned to Misdemeanor Court at 321 N. LaSalle St. He was convicted in December 1988 of failing to report cash income on his tax returns, but a mistrial was declared on more serious charges when jurors could not agree whether the money came from bribes.

Michael McNulty

Michael McNulty, an associate judge from 1977 until he resigned 10 years later, pleaded guilty to three counts of failing to report on his income tax returns cash bribes he received while presiding in Traffic Court in 1978, 1979 and 1980. McNulty admitted the income he failed to report was bribe money he had received from attorneys while he was a Traffic Court judge. He was sentenced to three years in prison and fined $15,000.

John Murphy

Judge John Murphy, branded by Operation Greylord prosecutors as a “judge for sale,” was convicted in 1984 of taking bribes and sentenced to 10 years in prison. His breakthrough conviction was the first against a sitting judge for judicial misconduct in Illinois. Murphy, who told an FBI mole posing as a corrupt lawyer that he could throw a case “out the window,” was found guilty of racketeering, extortion and mail fraud in a case prosecuted by U.S. Attorney Dan Webb and Scott Lassar, a future U.S. attorney.

U.S. District Judge Charles Kocoras branded Murphy an “infidel to the cause of justice” and focused serious criticism on Murphy for fixing scores of drunken driving cases while sitting in Traffic Court. Murphy told the judge: “I can show no remorse when I’ve done nothing to be remorseful for.” He was sentenced in August 1984 to 10 years in prison.

Jessica Arong O’Brien

The first Filipina judge in Cook County was sentenced to one year in prison after being convicted in a $1.4 million federal mortgage fraud scheme that occurred years before she took the bench. Judge Jessica Arong O’Brien was reassigned to administrative duties following her 2017 indictment and officially resigned from her post in 2018.

A jury found O’Brien guilty of fraud for scamming several lenders through the purchase of two South Side properties when she was a lawyer and real estate agent a decade earlier. She was convicted of lying to lenders to obtain more than $1.4 million in mortgages on the South Side investment properties. Prosecutors alleged O’Brien made a profit by unloading the two homes in 2007 to a straw purchaser who received kickbacks from O’Brien.

James Oakey

Former Judge James Oakey was indicted as part of Operation Greylord in 1986 for activities relating to his practice of law after he was removed from the bench for unrelated misconduct. He was convicted on racketeering, mail fraud and income tax charges in 1987 but was sentenced to 18 months in prison for the tax conviction only; a Supreme Court ruling had caused a judge to throw out the other convictions. At the 1988 sentencing hearing Oakey defiantly stated he “never squealed or ratted on my fellow man.”

In early 1989, after serving part of his prison sentence, Oakey entered a guilty plea that admitted he paid bribes to Operation Greylord Judge Richard LeFevour to have unrepresented defendants “steered” to Oakey’s law practice in 1982 and 1983. At his new sentencing hearing, a weeping and remorseful Oakey begged for mercy but received a six-year sentence.

Wayne W. Olson

Judge Wayne Olson, the first judge in U.S. history known to have his office bugged by federal agents, received a 12-year prison sentence in Operation Greylord for taking bribes to steer cases to lawyers and to fix cases while sitting as a narcotics court judge — despite a warning as early as 1980 that an investigation was underway. Olson, who was indicted in 1983, once told a defense attorney that he preferred “people who take dough because you know exactly where you stand,” according to a federal prosecutor. Olson pleaded guilty to charges that a former police officer who became a lawyer passed $9,120 in bribes to steer cases.

At sentencing, Olson said that while he served as a judge he was tempted with money, trips to Las Vegas, liquor and box seats for Chicago Cubs games. “I’m sorry to say, I gave in,” he said. “I’m guilty of being weak, of having weak moral fiber.” He was given 12 years in prison and fined $35,000.

John F. Reynolds

A longtime Cook County Circuit Court judge, John F. Reynolds was sentenced in 1986 to 10 years in federal prison for accepting kickbacks from corrupt attorneys and fixing three drunken driving cases in return for bribes. Reynolds had stepped down in 1984 as reports surfaced that he was under scrutiny as part of the Operation Greylord probe. He was found guilty of one count each of racketeering and conspiracy, of 31 counts of mail fraud and of filing false federal income tax returns for 1979, 1980 and 1981. Another two years was added to his sentence in June 1988 after he pleaded guilty to lying while under oath. In 1990, a federal judge dismissed mail-fraud charges against Reynolds.

Allen F. Rosin

Judge Allen F. Rosin was a judge for more than 20 years in the Domestic Relations Division — he once jumped over his bench and floored a man who began beating up his wife’s lawyer in the courtroom — then moved to the Law Division before losing his bid for retention in November 1986. Rosin fatally shot himself in the head in 1987 at a Near North health club, just two days before he was going to be indicted for taking payoffs as part of Operation Greylord, federal sources said at the time. Rosin’s fully clothed body — along with photos of his daughters and his military service medals — was found in a tanning booth in the McClurg Court Sports Center.

Rosin’s name had surfaced in 1985 during another judge’s trial, when a former police officer and admitted bagman testified that Rosin was among several Traffic Court judges who took bribes to fix drunken driving cases.

Frank Salerno

Judge Frank Salerno pleaded guilty to accepting payoffs to fix cases and was sentenced to nine years in prison. Accused of paying or taking bribes at all levels of the legal system almost as soon as he graduated from law school, Salerno was the first criminal defendant to be targeted with wrongdoing in both Operation Greylord and Operation Phocus, a probe of city of Chicago grants and zoning changes.

Many of his conversations were secretly tape-recorded by a teenage girlfriend who was introduced to him at a west suburban strip club where he was a customer and she was an employee, although she was only 16 at the time.

Out of 40 judges, the Chicago Bar Association failed to recommend just two for retention in September 1986 — Rosin and Salerno. Salerno was bumped from the bench during the next election and disbarred, but cooperated with both investigations. Prosecutors alleged Salerno was linked to the “hustlers’ bribery club,” a small band of lawyers who made payoffs to judges in return for the judges referring clients or letting the lawyers solicit clients in and around courtrooms.

Roger Seaman

Judge Roger Seaman, the first judge to testify for the prosecution in an Operation Greylord trial, was sentenced to five years in prison. Assistant U.S. Attorney Sheldon Zenner joked during Glecier’s trial that Seaman was so corrupt, “he would shake you upside down for money.”

The former assistant state’s attorney and former assistant Chicago corporation counsel pleaded guilty to two counts of mail fraud and one count of tax fraud. He testified he began taking bribes to satisfy his “greed” and gain acceptance from a group of crooked lawyers. Seaman testified he took hundreds of bribes from at least nine lawyers. He was voted off the bench in June 1983, following a Chicago Bar Association recommendation that said his integrity was questionable.

David Shields

Circuit Court Judge David Shields, the second most powerful judge in Cook County at the time, was found guilty in 1991 of pocketing $6,000 in bribes to rule favorably in a 1988 case secretly filed by the FBI as part of Operation Gambat, a corruption probe of the old 1st Ward. A 20-year veteran of the bench who presided over the Chancery Division, Shields was voted out of office in 1990 after his involvement in the probe became public. He was sentenced to 37 months in prison.

George J.W. Smith

George J.W. Smith pleaded guilty in 2002 to evading federal cash-reporting requirements in connection with what prosecutors said was his alleged purchase of his Cook County judgeship for $30,000. Smith told FBI agents in 2000 that he paid the cash to a cement contractor for remodeling work at his home, but Smith admitted in federal court that the government could prove that claim was a lie. As part of the federal probe, investigators subpoenaed records relating to the appointment of judges in Cook County as far back as 1990 and interviewed Illinois Supreme Court Justice Charles Freeman, who appointed Smith to the bench in 1995.

Raymond Sodini

Judge Raymond Sodini was sentenced to eight years in prison in Operation Greylord after a federal judge chastised him for overseeing a “cesspool of corruption.” Sodini abruptly pleaded guilty during his trial and admitted to accepting thousands of dollars in bribes. He was indicted for receiving more than $1,000 a month in payoffs for three years beginning in 1980 while presiding over Gambling Court, a misdemeanor branch court described as cramped, bug-infested and smelly.

In 1979, Sodini ordered clerks and deputy sheriffs to quit squabbling over bribes passed by attorneys and to “work it out among ourselves because there was enough there for everybody,” according to testimony by a former Cook County deputy sheriff. When he was too hung over to preside over the 8 a.m. “bum call,” Sodini asked a police sergeant to don his judicial robes and dispose of the drunks, vagrants and derelicts who had been arrested the night before, according to testimony presented during Sodini’s trial.

Sodini admitted his guilt during his own trial, saying he took bribes from lawyers to let them solicit unrepresented defendants who appeared in his courtroom, a practice known as “hustling.”

Roy Solfisburg

A special commission appointed by the Illinois Supreme Court concluded in 1969 that Chief Justice Roy Solfisburg and Justice Ray Klingbiel committed misconduct by participating in a case in which they had a financial stake and should resign. The investigative panel said the justices committed “positive acts of impropriety” by accepting gifts from Theodore J. Isaacs, a founder of the Civic Center bank, while they considered a case involving Isaacs in the Supreme Court. The commission’s report said it didn’t believe Solfisburg and Klingbiel were truthful in testifying they didn’t realize he was “one of the influential” organizers of the bank at the time they ruled in Isaac’s favor in the case. Though the justices denied wrongdoing, they both stepped down.

Interested in exploring the Tribune’s archives further? We’re partnering with Newspapers.com™ to offer a 1-month subscription to the Chicago Tribune archives for only 99 cents.