Lawyers for former House Speaker Michael Madigan want the jury in his corruption trial to see evidence that then-Ald. Daniel Solis allegedly cheated on his taxes while cooperating undercover with the federal government.

Before beginning a jury instruction conference Monday, Madigan’s lawyers revealed that they want to call Solis’ longtime accountant as well as a former IRS employee to testify about the then-alderman’s tax returns, which the defense has alleged failed to claim hundreds of thousands of dollars in payments Solis received from his sister.

Madigan’s legal team began putting on their case Dec. 19 before a long holiday break, but the identities of their upcoming witnesses had not been discussed in full on the public record.

Solis, the former head of the influential Zoning Committee, became a mole for the FBI in June 2016 and made a series of undercover audio and video recordings of Madigan that form the backbone of the prosecution’s case.

“What we are demonstrating is that he was committing crime while cooperating,” Madigan attorney Daniel Collins told U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey. The evidence would also show Solis had additional reason to curry favor with the government.

Prosecutors objected to some of the evidence coming in, saying any bias Solis had was “fully explored” on cross examination last month, and that including the evidence would risk creating an irrelevant sideshow about tax law.

“There is no need to add this additional layer” for the jury,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Diane MacArthur said Monday. She said assuming “there was a crime here in regard the tax returns” is “riddled with problems.”

Collins, however, said, the jury didn’t need to make any determination of guilt to conclude that Solis was compromised as a witness.

“I’m not going to ask the jury, ‘Hey, find Danny Solis guilty of this crime,’” Collins said. “Frankly, the government needs to investigate this information and determine whether a crime has been committed and whether it will be charged.”

During cross-examination of Solis in November, Collins grilled the former alderman over his connections to the Vendor Assistance Program, a venture started by his friend Brian Hynes and Solis’ sister, longtime Democratic operative Patti Solis Doyle. The program made millions by buying up unpaid bills from the state and then collecting late fees.

As a referral fee for connecting her with Hynes, Solis’ sister paid the alderman more than half a million dollars over a period about about seven years, much of which was never reported on Solis’ tax returns, Collins revealed in his questioning.

What’s more, Solis’s sister was recorded by the FBI telling her brother to “revise” financial records in his tax filings and claim the $230,000 she’d paid him in 2016 as capital gains on a prior investment — which was not true.

Solis testified he generally did not understand how taxes work and was acting on his sister’s recommendations.

“Did you realize that your sister was recommending tax fraud?” Collins asked.

“No,” Solis said.

It was also revealed Monday that the defense intends to call Madigan’s former law partner, Vincent “Bud” Getzendanner, to testify about long-standing ethical controls they used to avoid any potential conflicts of interest involving Madigan’s public positions.

Getzendanner, who was seen and heard on several of the undercover recordings made by Solis pitching the firm’s services to developers, is also expected to testify about the history of the firm and how it helped clients navigate Chicago’s complicated property tax assessment process.

Prosecutors said they object to Getzendanner testifying about what their firm would do in situations besides the ones at issue in the trial.

Blakey said he would rule on the witness issues before they take the stand.

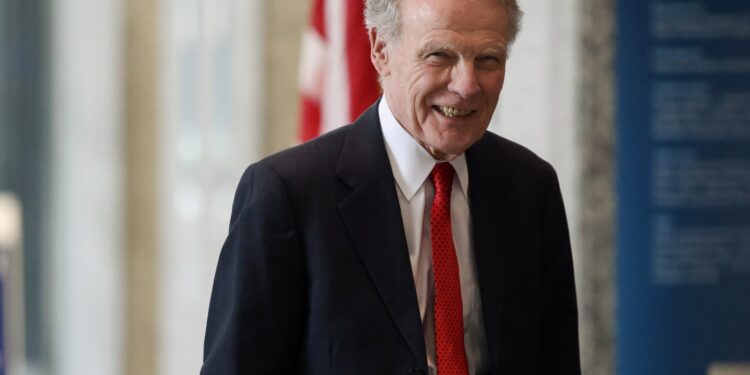

Madigan, 82, a Southwest Side Democrat, and his longtime confidant, Michael McClain, 77, of downstate Quincy, are charged in a 23-count indictment alleging Madigan’s vaunted state and political operations were run like a criminal enterprise to amass and increase his power and enrich himself and his associates.

In addition to pressuring developers to hire the speaker’s law firm, the indictment accuses Madigan and McClain of conspiring to have utility giants Commonwealth Edison and AT&T Illinois put the speaker’s associates on contracts requiring little or no work in exchange for Madigan’s assistance on key legislation in Springfield.

ComEd allegedly also heaped legal work onto a Madigan ally, granted his request to put a political associate on the state-regulated utility’s board and distributed bundles of summer internships to college students living in his Southwest Side legislative district, according to the charges.

Both Madigan and McClain have denied wrongdoing.

The trial, which began Oct. 8, is expected to head to closing arguments as soon as next week. Though jury instruction conferences are typically tedious, it’s taken on added importance in Madigan’s case after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June raised the bar for what prosecutors have to prove when it comes to the federal bribery statute contained in Madigan’s indictment.

In its decision in the bribery case of former Portage, Indiana, Mayor James Snyder, the high court ruled that “gratuities” — or gifts given as a thank-you for actions a public official has already taken — are not criminalized under the federal statute, and that prosecutors must prove there was an agreement ahead of time.

A jury appeared to be struggling over that very issue before deadlocking in September in the trial of former AT&T Illinois boss Paul La Schiazza, who was accused of bribing Madigan in an alleged scheme that also is part of Madigan’s case.

Earlier this month, La Schiazza’s attorneys lost a bid to throw out the charges, and the case is now set for retrial in June.

Blakey, meanwhile, declined to dismiss any of the bribery counts against Madigan, saying the indictment clears the hurdle set in the Snyder case by alleging Madigan performed official acts in exchange for various things of value, including the ComEd jobs for his associates.

Still, the high court’s ruling is sure to influence the language the jury receives in the legal instructions, which will lay out what prosecutors need to prove on the five bribery counts included in the indictment.

Blakey had hoped that by the time the trial wrapped, the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals would have new pattern jury instructions that would deal with the Snyder ruling.

But earlier this month the judge told the parties the new pattern instructions would not be ready in time.