In advance of this year’s state legislative sessions, lawmakers are filing more than a dozen bills to expand abortion access in at least seven states, and a separate bill introduced in Texas seeks to examine the impact that the state’s abortion ban has had on maternal outcomes.

Some were filed in direct response to ProPublica’s reporting on the fatal consequences of such laws. Others were submitted for a second or third year in a row, but with new optimism that they will gain traction this time.

The difference now is the unavoidable reality: Multiple women, in multiple states with abortion bans, have died after they couldn’t get lifesaving care.

They all needed a procedure used to empty the uterus, either dilation and curettage or its second-trimester equivalent. Both are used for abortions, but they are also standard medical care for miscarriages, helping patients avoid complications like hemorrhage and sepsis. But ProPublica found that doctors, facing prison time if they violate state abortion restrictions, are hesitating to provide the procedures.

Three miscarrying Texas women, mourning the loss of their pregnancies, died without getting a procedure; one was a teenager. Two women in Georgia suffered complications after at-home abortions; one was afraid to seek care and the other died of sepsis after doctors did not provide a D&C for 20 hours.

Florida state Sen. Tina Polsky said the bill she filed Thursday was “100%” inspired by ProPublica’s reporting. It expands exceptions to the state’s abortion ban to make it easier for doctors and hospitals to treat patients having complications. “We’ve had lives lost in Texas and Georgia, and we don’t need to follow suit,” the Democrat said. “It’s a matter of time before it happens in Florida.”

Texas state Rep. Donna Howard, who is pushing to expand the list of medical conditions that would fall under her state’s exceptions, said she’s had encouraging conversations with her Republican colleagues about her bill. The revelations that women died after they did not receive critical care has “moved the needle here in Texas,” Howard said, leading to more bipartisan support for change.

Republican lawmakers in other states told ProPublica they are similarly motivated.

Among them is Kentucky state Rep. Jim Gooch Jr., a Baptist great-grandfather who is trying for the second time to expand circumstances in which doctors can perform abortions, including for incomplete miscarriages and fatal fetal anomalies. He thinks the bill might get a better reception now that his colleagues know that women have lost their lives. “We don’t want that in Kentucky,” he said. “I would hope that my colleagues would agree.”

He said doctors need more clearly defined exceptions to allow them to do their jobs without fear. “They need to have some clarity and not be worried about being charged with some type of crime or malpractice.”

After a judge in North Dakota overturned the state’s total abortion ban, Republican state Rep. Eric James Murphy acted quickly to stave off any similar bans, drafting a bill that would allow abortions for any reason up to the 16th week and then up through about 26 weeks if doctors deem them medically necessary.

“We need other states to understand that there’s an approach that doesn’t have to be so controversial,” said Murphy, who is also an associate professor of pharmacology at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “What if we get the discussion going and we get people to know that there are rational Republicans out there? Maybe others will come along.”

Under state rules, North Dakota lawmakers are required to give his bill a full hearing, he said, and he plans to introduce ProPublica’s stories as evidence. “Will it make it easier? I sure hope so,” he said. “The Lord willing and the creeks don’t rise, I sure hope so.”

Good journalism makes a difference:

Our nonprofit, independent newsroom has one job: to hold the powerful to account. Here’s how our investigations are spurring real world change:

We’re trying something new. Was it helpful?

So far, efforts to expand abortion access in more than a dozen states where bans were in effect have faced stiff opposition, and lawmakers introducing the bills said they don’t expect that to change. And some lawmakers, advocates and medical experts argue that even if exceptions are in place, doctors and hospitals will remain skittish about intervening.

As ProPublica reported, women died even in states whose bans allowed abortions to save the “life of the mother.” Doctors told ProPublica that because the laws’ language is often vague and not rooted in real-life medical scenarios, their colleagues are hesitating to act until patients are on the brink of death.

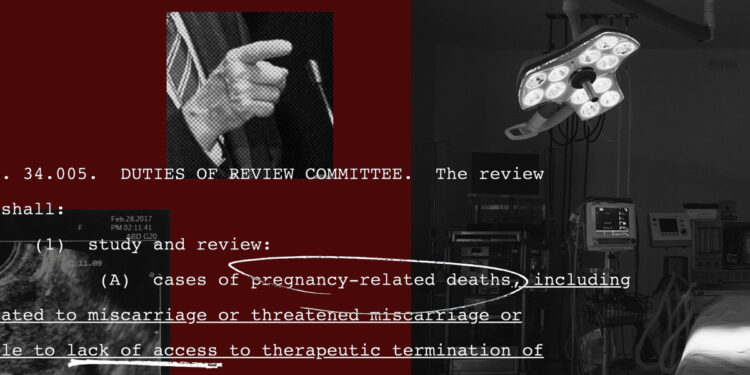

Experts also say it is essential to examine maternal deaths in states with bans to understand exactly how the laws are interfering with critical care. Yet Texas law forbids its state maternal mortality review committee from looking into the deaths of patients who received an abortive procedure or medication, even in cases of miscarriage. Under these restrictions, the circumstances surrounding two of the Texas deaths ProPublica documented will never be reviewed.

“I think that creates a problem for us if we don’t know what the hell is happening,” said Texas state Sen. José Menéndez.

In response to ProPublica’s reporting, the Democrat filed a bill that lifts the restrictions and directs the state committee to study deaths related to abortion access, including miscarriages. “Some of my colleagues have said that the only reason these women died was because of poor practice of medicine or medical malpractice,” he said. “Then what’s the harm in doing the research … into what actually happened?”

U.S. Rep. Jasmine Crockett agreed. The Texas Democrat and three other members of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability on Dec. 19 sent a letter to Texas state officials demanding a briefing on the decision not to review deaths that occurred in 2022 and 2023.

Crockett said the state has not responded to the letter, sent to Texas Public Health Commissioner Jennifer Shuford.

“If you feel that your policies are right on the money, then show us the money, show us the goods,” she said. “This should be a wakeup call to Texans, and Texans should demand more. If you believe that these policies are good, then you should want to see the numbers too.”

Doctors are starting to hear about heightened concerns in conversations at their hospitals.

Dr. Austin Dennard, a Dallas OB-GYN, said her hospital recently convened a meeting with lawyers, administrators and various specialists that focused on “how to keep our pregnant patients safe in our hospital system and how to keep our doctors safe.” They discussed creating additional guidance for doctors.

Dennard, who noted she is speaking on her own behalf, said she is getting more in-depth questions from her patients. “We used to talk about vitamins and certain medications to get off of and vaccines to get,” she said. “Now we do all that and there’s a whole additional conversation about pregnancy in Texas, and we just talk about, ‘What’s the safest way we can do this?’”

In addition to being a doctor, Dennard was one of 20 women who joined a lawsuit against the state after they were denied abortions for miscarriages and high-risk pregnancy complications. When she learned her fetus had anencephaly — a condition in which the brain and skull do not fully develop — she had to travel out of state for an abortion. (The lawsuit asked state courts to clarify the law’s exceptions, but the state Supreme Court refused.)

Dennard said stories like ProPublica’s have crystallized a new level of awareness for patients there: “If you have the capacity to be pregnant, then you could easily be one of these women.”

Mariam Elba contributed research and Kavitha Surana contributed reporting.