The operating word of the Democratic National Convention was “vibes.” They’re good, if you haven’t heard. They’ve shifted. For a group of people often dismissively referred to as “bedwetters,” Democrats are as excited as they’ve ever been at having a roughly 50-50 chance of disaster. There was just a feeling. Everyone from Bill Clinton to Oprah wanted to talk about the “joy” the new nominee brought to the race. Attendees told me it felt like 2008. “Yes she can,” said Barack Obama. People carried around prints of Vice President Kamala Harris that looked like Shepard Fairey had painted them. I thought I even saw Bill Ayers while walking around in his old neighborhood on Sunday.

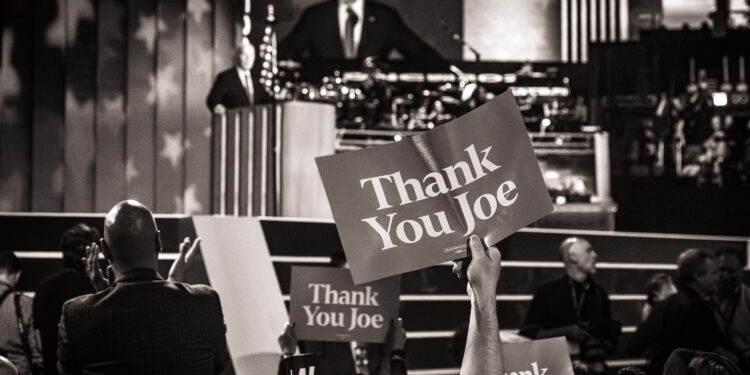

A few months ago, such a display of Democratic optimism would have felt impossible. For much of the last eight years, the Democratic Party has been defined by a simmering discontent over the administrations of the past and the primary battles that never ended. Biden, elected in an economic crisis and a global pandemic, had promised to serve as a transitional figure before yielding to a new generation of leaders. But as his reelection bid stumbled, he seemed, instead, like a bridge to nowhere.

Chicago offered a glimpse of what a soft-landing looks like, not just for the economy, but for a whole political party. Years of infighting and recriminations yielded a policy consensus that sounded like an unusually appealing kind of working-class fusionism. Adding dental and vision coverage to Medicare. Stopping corporate price-gouging. Busting monopolies. Passing the PRO Act. Free school lunch and breakfast. On Wednesday, Tim Walz’s small-town biography doubled as a story not just about football defensive schemes, but about the crushing weight of medical debt and the imperative for government to wipe it out.

The sorts of issues that had often festered for years on the party’s left-flank were dressed up in a kind of general-interest dad plaid, and pitched to a willing audience by people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The new consensus did not just happen all at once. It happened, in part, because the current president rebuilt trust in what normie Democrats could accomplish. Biden was a bridge after all. Democrats in Chicago finally found out what was on the other side.

The change within the party was not just a matter of positive thinking. It was reflected in the substance of the event. The spectacle in Chicago was the total inverse of what transpired at the RNC. In Milwaukee, Trump and Vance had dangled the possibility of a new conservative workers party, in the service of an increasingly monarchical donor class. To make their case, they even rolled out a prominent labor leader, Teamsters president Sean O’Brien, who argued that unions should seek friends in the Republican Party in the fight against “economic terrorism.” O’Brien’s gimmick seemed a bit credulous at a coronation for a corrupt plutocrat who had kneecapped organized labor as president; it looks even more foolish now.

While the RNC offered the illusion of transformation, Democrats showed off their capacity to actually change, and to elevate new leaders and ideas in the service, often enough anyway, of a politics for working people. Instead of O’Brien, the DNC gave a primetime platform to Shawn Fain, the United Auto Workers president, who took off his blazer midway through his speech on Monday to reveal a red union t-shirt that said “Trump is a scab.”

Fain, who took office in 2023, represented a new direction for an old institution. He was the product of a political revolution within the UAW, aimed at driving out stagnant and corrupt leadership, and as president, he pursued a more aggressive strategy, which culminated in a historic strike at the Big Three automakers last year. (Full disclosure, I am a member of the UAW.) His spokesman is a former organizer for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, and Fain rails frequently against “the billionaire class.” But his presence on stage spoke not just to a more ambitious and assertive labor movement, but also to the power of real political partnership—and the changes that Biden, of all people, had brought to politics.

The new consensus did not just happen all at once. It happened, in part, because the current president rebuilt trust in what normie Democrats could accomplish. Biden was a bridge after all.

The union’s recent successes, he pointed out every chance he got in Chicago, were powered by members but eased along by the White House. In remarks to reporters this week, Fain credited Biden’s revamped National Labor Relations Board, which Trump had stacked with corporate picks, for clearing the way for clean elections at notoriously difficult shops. When auto workers went on strike last year, Biden, Fain noted, became the first president to ever walk a picket line. And when workers struck in 2019, Harris, as a presidential candidate, was there too.

“Plants were closing under Donald Trump,” Fain said. “I didn’t see Donald Trump save one of them. I didn’t see Donald Trump try to save one of them.”

Fain was a ubiquitous figure throughout the week in running shoes and a rotating array of red and blue UAW shirts. The union had sold thousands of “Trump is a scab” tees since his speech on Monday. Everywhere he went, delegates—many in red union shirts of their own—would gather around him to have a word or take a photo. (He was also multi-tasking—Fain used his speech to deliver a message to Big Three automaker Stellantis, and even took a bus trip during the week to rally outside the company’s plant in Belvidere, Illinois.) On Wednesday morning, after watching Fain quote Ecclesiastes and the “great poet…Marshall Mathers” within the span of a few minutes at a breakfast with the Michigan delegation, I asked him about the party’s trajectory.

“After the Reagan years and Bush 1, you saw a shift somewhat where, because laws changed, deregulation happened, the massive tax cuts for the wealthy, trickle-down economics…and I think the party somewhat shifted to try to appease the business class and the corporate class,” he said, as we walked down an escalator at a Michigan Ave. Hilton. “I think that hurt in the elections, because when people look at both sides, they see the same people serving the same master.”

Things were looking up, though. He believed that Harris and Walz, like Biden, would bring the party closer to its “working-class roots.”

“It’s gonna take time—it’s not gonna happen overnight,” he said. “But we’re on our way.”

The week was a passing of the torch of sorts, not just for Biden and Clinton, but for the man who lost the nomination to both of them, Bernie Sanders. The Vermont senator, a more hunched but still fiery 82, is seeking a fourth and perhaps final term this fall, while still mostly talking about the same issues he’s been harping on for four decades—getting money out of politics, universal health care, and tackling “oligarchy.” At a small confab near the United Center hosted by his longtime allies at the Progressive Democrats of America on Monday, Sanders made a forceful case that the man whom Democrats had rallied behind to stop him from winning the nomination had been a real ally once in office.

“He was prepared to really bring about structural changes in this country,” Sanders explained, laying out a wish list from childcare to adding dental and vision coverage into Medicare. “That was Build Back Better, and we failed with the two corporate Democrats in the Senate—but what I want you to understand is he was prepared to do that.”

“You’re not gonna hear a lot about Medicare for All” at the convention, Sanders acknowledged. (Harris, who embraced a variation of the policy in 2019 during her presidential campaign, walked back her support this month.) But Sanders had been a leading voice calling for Biden to stay in the race, in part because of the strength of their working relationship. Although he and Harris are not as close, Sanders sounded positive when we spoke later that night about what a Harris administration might portend.

Harris said the words “we are not going back” six times. The dig at Trump was obvious. But it describes where the party is at too.

“I think the proposals that she has brought forth so far are strong proposals,” he said. “I’m really glad that she is focusing on housing, because I will tell you that it’s an area that has not gotten the attention that it deserves. And she’s right. You got a major housing crisis in Burlington, Vermont, Los Angeles, and every place in between, 650,000 people homeless, millions unable to afford housing, so I’m glad she’s focusing on that. I’m glad she’s continuing the efforts to lower the cost of prescription drugs, which is a huge issue. I’m glad she believes in eliminating medical debt, which is just insane that people go bankrupt because they have cancer. So that’s an important issue, and extending the child tax credit that we passed in the rescue plan to lower childhood poverty by 40 percent is also enormous. So I think she’s off to a good start.”

One of the reasons he was feeling optimistic, Sanders said this week, was because of what he called “the rebirth and revitalization of the trade union movement.” In Biden, he had found an ally on the inside, but in Fain—whom he singled out for wearing an “Eat the Rich” shirt during last year’s strike—Sanders saw the vanguard of a workers movement often aligned with the Democratic Party that could continue to drive change outside of it.

The gerontocracy at the top of the party has for a long time created the impression of a stultifying institution. The narrowness of the message Biden was capable of articulating—in contrast to the substance of the policies he was working to deliver—created an oppressive sort of aura. It was all harshly whispered words about “democracy” and the “soul of the nation.” Biden was standing in the way of not just Harris, but of a broader generational transition capable of saying so much more.

It wasn’t just Fain. Ocasio-Cortez, a fellow insurgent once on the fringes on the party, now had roughly the same prominence in the speaker lineup as Hillary Clinton, and attacked the Republican nominee as a “two-bit union-buster.” Everywhere you looked, there was some new star in the coalition, or soon-to-be-star in the coalition, seizing their five to 15 minutes to make their case. Many of these figures weren’t even in politics during the 2016 primaries. Their ideas and careers had been forged in the reactionary crucible in the Trump years.

Perhaps no one embodied this breakthrough better than Harris herself, a politician whose 2020 presidential candidacy floundered in a party still stuck in 2016, and who wallowed as an occasional punchline as vice president for three years.

“[O]ur nation, with this election, has a precious, fleeting opportunity to move past the bitterness, cynicism and divisive battles of the past, a chance to chart a new way forward, not as members of any one party or faction, but as Americans,” she said in her remarks at the United Center. She said the words “we are not going back” six times. The dig at Trump was obvious. But it describes where the party is at too.

Going into the week, the grumbling, among the grumbling set, was that Harris was big on sunshine and light on specifics. But the program is simple enough: Making things easier for working-people, in easily recognizable ways—affordable housing, affordable groceries, affordable drugs, and affordable families too; the Child Tax Credit that Sanders promoted is such a popular idea that the Republicans who killed it are now running on bringing it back.

Democrats were also clear-eyed about what they were up against. Throughout the week, a procession of people—Michigan state Sen. Mallory McMorrow (first elected: 2018); Pennsylvania state Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta (first elected: 2018); Saturday Night Live star Kenan Thompson—stepped up to the lectern with a comically oversized book, like something out of an old Cistercian Abbey, and announced that this was “Project 2025.”

During Thompson’s faux-SNL sketch, regular people took turns describing their life circumstances, and then Thompson would page through his big book and tell them how they were screwed. A woman named Nirvana happily announced that thanks to Biden and Harris, she pays just $35 a month for insulin. That was getting axed, Thompson cheerfully informed her. Another person said she was an employee at the Department of Education. She would be fired, Thompson explained. Someone else was happily married to a spouse of the same sex. Womp, womp.

The Project 2025 attacks were the sort of policy evisceration—at various points mean and fun and deeply moving—that I hadn’t seen in such portions since Obama’s scorched-earth campaign against Bain Capital and Paul Ryan’s budget. It is hard to say anything new about Trump. But the key to the Project 2025 attacks was that they didn’t just define Republicans as weird and creepy (although they did do that, in a mix of gut-wrenching and clever ways). That big oversized think-tank document gave Democrats a chance to talk about the things they consider normal. They were unafraid to talk about abortion. They went out of their way to talk about fertility treatments. They stood for the bedrock principle of doing what the doctor tells you to do. It fell to Walz, another relative unknown until Biden’s exit, to sum up this new middle-ground in his characterstically blunt way: “Mind your own damn business.”

The vibesiest scene at the DNC’s vibes-fest this week may have come at “Hotties for Trump,” an after-party where hundreds of zoomers picked up “Fuck Project 2025” condoms and posed for photos next to a couch that said “Property of JD Vance.” The event was bankrolled, like tens of millions of dollars worth of other Democratic operations, by the LinkedIn billionaire Reid Hoffman.

Like the entire Harris campaign itself, the Democratic coalition’s kumbaya feel is fragile and potentially fleeting. There are already signs of potential crackups in this new unified front. “There are some Democratic donors who don’t like Lina Khan,” Sanders told me. “I happen to think that Lina Khan is the best chair of the FTC that we have seen in a very long time.”

Hoffman begs to differ, and in his criticism of one of the Biden administration’s most effective Big Tech trust-busters, you can see the shape of the battles to come. Those grocery stores where Harris wants to crack down on rising costs, for instance, include chains like Kroger—whose merger with Albertson’s Khan has put on hold. The week’s most glaring stain was the refusal to grant speaking time to a Palestinian-American Georgia state representative and Harris delegate—the sort of cynical and short-sighted move that may haunt a group of people who claim to be the party of moral clarity. And for all their positivity, Democrats are still more or less a coin flip from another catastrophe in November, and a new wave of recriminations and soul-searching.

For Democrats, the future is promising but uncertain. But they have, at least, finally left the past behind.