This story was originally published on June 11, 2024. We are republishing it on the occasion of Inside Out 2‘s arrival on Disney+ on Sept. 25, 2024.

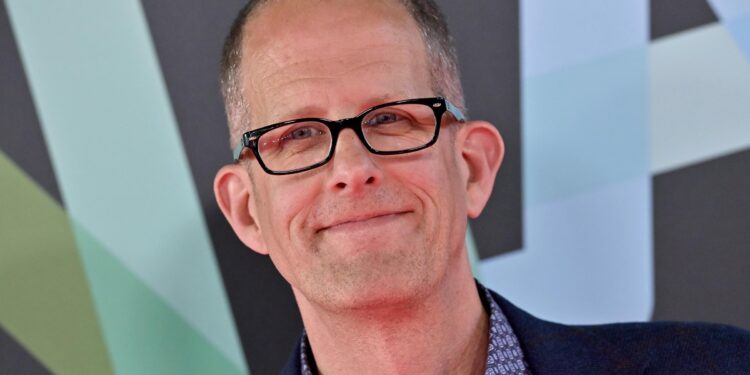

Pete Docter knows the stakes are high for Inside Out 2. Docter started at Pixar when he was 21, and quickly rose through the ranks, working on classics like Toy Story. He went on to direct films like Up and Monsters Inc. as well as the original Inside Out, the most profitable non-sequel Pixar has ever produced. In 2018, he was named Pixar’s Chief Creative Officer. He’s racked up nine Oscar nominations, with three wins.

But in recent years, Pixar has found itself in a commercial and critical rut. Movies like Turning Red and Luca that were largely based on creators’ own childhoods didn’t seem to resonate with audiences the way that more universal tales like Toy Story and Monsters Inc. did. Docter points out it can be difficult to come up with original ideas that resonate with a wide audience two decades into the studio’s existence. “A lot of people say, ‘I totally thought toys came to life when I wasn’t in my room.’ ‘I totally believed there were monsters in my closet,’” he says. “We’re still rummaging around for things like that, but it’s harder and harder to find as we’re into our 28th movie or whatever.”

And ever since Disney put movies like Turning Red, Luca, and Soul (the last of which Docter co-directed) on its streaming service Disney+ during the pandemic, Pixar has struggled to coax audiences back to theaters. In the last two years, Lightyear and Elemental both failed to meet opening weekend expectations at the box office. The studio has been forced to overhaul its creative vision and business strategy by returning to the properties that won over fans in the first place, like Inside Out.

Box office prognosticators have predicted that Inside Out 2 will become one of the highest-grossing movies of 2024. And theater owners are praying that it will drive families to the cinema in a year that’s been light on kid-friendly content. Overall, it’s been an abysmal year at the movies. The Memorial Day box office hit a 26-year low after several big-budget films underperformed. It may be that audiences just want to watch movies—especially kids’ movies—at home rather than forking over a hefty sum to take the family to the theater.

The future of Pixar, this year’s box office, and theaters in general may hinge, in part, on the success of movies like Inside Out 2. “If this doesn’t do well at the theater, I think it just means we’re going to have to think even more radically about how we run our business,” says Docter.

Inside Out 2 picks up a few years after the events of its predecessor with a girl named Riley preparing for high school. The anthropomorphized emotions that live inside Riley’s head and help to steer her through the world—Joy, Sadness, Anger, Disgust, and Fear—wake in the middle of the night to a blaring “Puberty” alarm and the introduction of new roommates: Embarrassment, Ennui, Jealousy, and Anxiety. Joy (Amy Poehler) and Anxiety (Maya Hawke) tussle over how to steer Riley through the awkward teenage years.

Docter spoke to TIME about why Pixar is focusing much of its energy on making more sequels, how they can find universal ideas that connect with large audiences, and why you won’t see live-action adaptations of Pixar’s animated movies. (Sorry, Josh O’Connor. That means no Ratatouille remake.)

Why did you think there was enough in the Inside Out story for a sequel?

We’ve built the entire ocean for Nemo, the entire universe for Wall-E. But it turned out the biggest set we had built [when Inside Out debuted] was inside of a little girl’s mind. We only saw like 3% of it in the first film. There was way more to play with, and we had a lot of leftover ideas.

But the big question is, was there something substantive? We tapped Kelsey Mann, who was head of story on Onward and Monsters University, and he ran off and thought of this idea having to do with anxiety. It felt like that’s something that was really ripe.

My editor showed the trailer to her kids, and they were like, “What’s anxiety?” Do you think that concept will go over the head of a six-year-old?

Yes, though so did things like Anger or Sadness [in the first movie]. After the first film, we heard story after story of people saying, “I now have tools to talk about this stuff with my kids.”

That was true especially of little boys who have a lot of trouble talking about emotions. I don’t know if that’s genetics or a societal thing. But either way, they really connected, especially with Anger. One of the great gifts of this project is taking these abstract ideas and making them real.

You have talked about how releasing Pixar movies straight to Disney+ trained audiences to expect those movies on streaming. How do you get audiences to go to the theater for Pixar movies again?

Part of our strategy is to try to balance our output with more sequels. It’s hard. Everybody says, “Why don’t they do more original stuff?” And then when we do, people don’t see it because they’re not familiar with it. With sequels, people think, “Oh, I’ve seen that. I know that I like it.” Sequels are very valuable that way.

On the other hand, they’re almost harder than originals because we can’t do the same idea again. We have to build on it hopefully in ways that people don’t expect.

Lightyear underperformed at the box office. If the focus is more sequels and spin-offs, what’s the lesson from that spin-off not working?

We took a long moment of self scrutiny after that didn’t deliver. I think we overestimated the audience’s nerd level of being like, “Oh, that kid in the first Toy Story bought a toy, and it was based on a movie. And this is that movie.” That’s probably a few layers too deep. Because I think people are going, “Well, where’s Mr. Potato Head? Where’s Woody?”

What are you looking for when it comes to ideas for original movies that will get people to theaters?

It’s sort of cynical to say people want to see stuff they know. But I think even with original stuff, that’s what we’re trying to do too. We’re trying to find something that people feel like, “Oh yeah, I’ve been through that. I understand that I recognize this as a life truth.” And that’s been harder to do.

A lot of people say, “I totally thought toys came to life when I wasn’t in my room.” “I totally believed there were monsters in my closet.” We’re still rummaging around for things like that, but it’s harder and harder to find as we’re into our 28th movie or whatever.

A recent Bloomberg article emphasized that going forward, Pixar is going to prioritize universality over specificity—which means fewer movies inspired by a creator’s specific childhood experiences, and more based on universal truths. But as journalists, we’re taught the specific is the universal.

I believe that too.

So how do you find that balance?

I think there was a bit of a misunderstanding about that because it’s not that [those movies were] too specific. But what I’ve found is sometimes, if you are telling a personal story, you’ll be like, “Oh, no, that’s not the way the story goes. Because my story is this.” But we’re not telling my story; we’re telling a story that needs to work for a fictional character that we’re creating. So there’s sometimes a reluctance to let go or let the movie shape itself the way it needs to.

Nemo is very personal. Obviously, [writer-director] Andrew Stanton is not a fish, and he’s not a single dad. But he recognized his own smothering of his child in an effort to protect them. He was able to springboard off of that to tell stories about octopuses and all sorts of wild, fun stuff.

The story shouldn’t come fully formed. You’re always adding and removing stuff. It’s an organic, messy process. But sometimes, your own personal experience can drive that and other times it can get in the way.

Practically, how does that work? The Pixar braintrust gives more input into every movie?

Avoid being seduced by “This is really clever.” We want to drill down before they go into production to be like, what’s the core idea? Okay, this is really about the struggles of being a parent or the struggles of losing a loved one.

I know Pixar is stepping away from doing as much short-form content for Disney+ in order to focus on features. But Bluey, which has eight-minute-long episodes, has become wildly popular on Disney+. And I think part of the reason they’re so successful is we have short attention spans now. Does that pressure Pixar to explore that short-form space again?

Well, when they first announced Disney+, we immediately jumped in with a bunch of shorts. Turns out the audience didn’t want short little things from Pixar at least. It just didn’t perform as well. It didn’t earn its keep in terms of what we had to put into it to make them. So Disney asked us to pull back on anything that’s not the features.

We’ve also found the better [a movie] does at the theater, the more successful it has been on Disney+. Initially you’d think if it does really well in the theater, nobody’s going to watch it on Disney+ because we’ve seen it already. It’s actually the opposite, which kind of makes sense. I remember as a kid I had The Muppet Show album, and I played that thing to death. As a kid you want the comfort of watching this one thing over and over and over.

That’s true for us on Disney+. I don’t know if it’s true on Netflix.

I actually saw this morning that Super Mario Bros. has been on the Top 10 Netflix chart for 25 weeks. To your point, that movie did well in theaters and now it’s doing well on streaming.

That’s the same model. You know, I would love to push the theatrical window more. I’m no businessman, but just creatively it’d be great to make audiences feel if you don’t see this now, it’s going to be awhile before it’s readily available at your house.

I’ve been shocked by how many big-budget movies this summer have wound up on PVOD (premium video on demand) two weeks after their release.

It’s crazy.

Inside Out 2 has a 100-day release window. That feels like a statement.

That’s how long we had for Elemental. When that movie came out we all said, “Oh, no, that didn’t open the way we thought it should!” But as time went on, it just had legs. I don’t know if the marketing was wrong, the space was too crowded, or people thought it didn’t look interesting. But word of mouth made people go check it out. I think that would not have happened if we came out three weeks later on Disney+.

Industry analysts have really built up the opening weekend of Inside Out 2. If it doesn’t succeed, the summer box office is doomed. If it doesn’t succeed, Pixar is doomed. How do you see the stakes?

I can’t imagine having a better chance at a big box office than this because it’s a known movie and characters that meant something to people and a really funny cast—and hopefully something meaty at the heart of it that you can take home as well.

So if this doesn’t do well at the theater, I think it just means we’re going to have to think even more radically about how we run our business. So far Pixar has built a business around pretty large budgets. It allows us to make a lot of mistakes and take risks, and if it doesn’t work, we can still go back and fix it.

I think if you really want to make it cheap, you think of an idea, and you make it. But if you want to make it good, you have to change and iterate a ton and that’s what we’ve been able to do so far. If the box office doesn’t support that, if the economics don’t support that, we just have to make even more giant shifts.

What shifts have been made? [Pixar had a round of layoffs in May.]

We’ve already been able to tuck our budgets way down. We’ve made films in much fewer weeks.

In the Monsters Inc. through Ratatouille days there was—I was going to say opulence, but that’s not the right word. There was much more freedom to explore. And now we’re tightening the belt and we’re really going to be targeted about when we take risks.

You mentioned Ratatouille. I don’t know if you’re aware that Josh O’Connor, one of the stars of Challengers, has been talking nonstop on his press tour about his love of Ratatouille.

No!

And there is a fan campaign to get him cast in a live-action Ratatouille. Are live-action adaptations something you guys would ever consider?

No, and this might bite me in the butt for saying it, but it sort of bothers me. I like making movies that are original and unique to themselves. To remake it, it’s not very interesting to me personally.

That’s maybe for the best because I don’t know how you make a live-action rat cute.

It would be tough. So much of what we create only works because of the rules of the [animated] world. So if you have a human walk into a house that floats, your mind goes, “Wait a second. Hold on. Houses are super heavy. How are balloons lifting the house?” But if you have a cartoon guy and he stands there in the house, you go, “Okay, I’ll buy it.” The worlds that we’ve built just don’t translate very easily.