By Jack Queen

(Reuters) – In Arizona, one of seven competitive U.S. states that are expected to decide the 2024 presidential election, an advocacy group founded by Donald Trump adviser Stephen Miller is advancing a bold legal theory: that judges can throw out election results over “failures or irregularities” by local officials.

The lawsuit by the America First Legal Foundation, a conservative advocacy group, says the court in such cases should be able to toss the election results and order new rounds of voting in two counties in Arizona, where Democratic candidate Vice President Kamala Harris is leading Trump in the polls by a razor-thin margin.

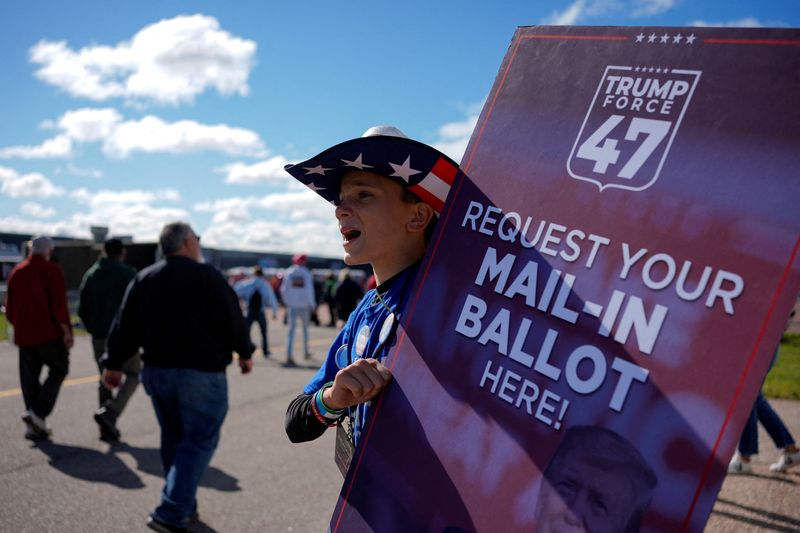

Almost four years after former president Trump and his allies tried and failed to overturn his election defeat with a flurry of more than 60 hastily arranged lawsuits, Republicans have launched an aggressive legal campaign laying the groundwork to challenge potential losses.

The Republican National Committee says it is involved in more than 120 lawsuits across 26 states, in a strategy that some legal experts and voting rights groups say is meant to undercut faith in the system.

Republicans say the lawsuits are aimed at restoring faith in elections by ensuring people don’t vote illegally. Trump and his allies have falsely claimed that his 2020 election loss to Joe Biden was tainted by widespread fraud.

While the Arizona case is likely a long shot, legal experts say it fits with a pattern of Republican-backed lawsuits that appear aimed at sowing doubts about the legitimacy of the election before it occurs and providing fodder for challenging the results after the fact.

“This is part of creating the narrative that there will be irregularities that will require outside intervention,” said Columbia Law School professor Richard Briffault.

America First Legal Foundation, its lawyers and Miller did not respond to inquiries.

A spokesperson for the Republican National Committee said the party’s top priority is fixing what they say are problems with voting systems before Election Day to ensure no ballots are illegally cast.

“Our Election Integrity operation is fighting to secure the election, promoting transparency and fairness for every legal vote. This gives voters confidence that their ballot will be counted properly, and in turn, inspires voter turnout,” said RNC spokesperson Claire Zunk.

Trump and Harris are locked in a tight battle ahead of the Nov. 5 election, fueling a wave of litigation by both Democrats and Republicans as they spar over the ground rules.

Republicans typically sue to enforce restrictions on voting that they say are necessary to prevent fraud, while Democrats generally ask courts to keep voting accessible.

The Harris campaign said in a statement that Republicans are “scheming to sow distrust in our elections and undermine our democracy so they can cry foul when they lose.”

“Team Harris-Walz enters the home stretch of this campaign with a robust voter and election protection operation and the best lawyers in the country, ready for any challenge Republicans throw at us. We will give Americans the free and fair election they deserve so all eligible voters can vote and have that vote counted,” the campaign said.

In Michigan, another closely contested state, Republicans are suing to prevent state agencies from expanding access to voter registration, restrict the use of mobile voting sites like vans and impose tighter verification rules for mail-in ballots.

In Nevada and other states, Trump allies are seeking to purge voter rolls of allegedly ineligible voters and noncitizens, though the deadline for systematically culling rolls in time for the election has passed.

And in Pennsylvania, Republicans are fighting to enforce strict mail-in voting rules and limit voters’ ability to correct mistakes on their ballots. On Sept. 13, Republicans scored a victory when the state’s highest court ruled mail ballots with incorrect dates will not be counted.

SOWING CONFUSION

Election litigation surged in 2020 as COVID-19 spurred changes to voting procedures wider use of mail-in ballots. Those fights were often reactions to granular, location-specific issues.

More than 60 lawsuits Republicans filed challenging Trump’s loss in 2020 were rejected by courts.

This time, Republicans are filing legal challenges earlier and leveling allegations of widespread fraud that strike to the very core of the election process.

Trump’s continued false claims that his 2020 defeat was the result of fraud has taken root in the Republican Party: 71% of Republican registered voters responding to an August Reuters/Ipsos poll said they believed voter fraud was a widespread problem, well above the 37% of independents and 16% of Democrats who held that view.

“They’re out front and early and are moving preemptively, whereas 2020 was kind of reactive. Here they’re getting ahead of it,” Briffault said.

The Arizona lawsuit, filed in February in Yavapai County court, underscores the proactive approach by Trump’s allies. It alleges a litany of “missteps and illegalities” by election officials in Maricopa, Yavapai and Coconino counties in past election and asserts that only court intervention can restore the public trust.

Maricopa County was dismissed from the case on procedural grounds.

The complaint asks a judge to impose a list of 24 orders enforcing the America First Legal Foundation’s interpretation of election laws and correcting errors by any means necessary, including nullifying results and ordering new rounds of voting.

Errors could include failure to staff ballot drop boxes at all times or failing to take certain steps to verify signatures on ballots.

That is a novel and sweeping request that a judge is unlikely to grant, according to legal experts and election attorneys. But a judge nullifying results in a crucial state could lead to chaos, confusion and delays, which some legal experts and voting rights group say is a central goal of the Republican legal strategy.

Uncertainty could give local officials and state legislatures the opportunity to meddle with the results, according to Sophia Lin Lakin, an attorney litigating voting rights cases on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union. For example, officials could try to throw out votes or refuse to certify the outcome.

“It’s about laying the groundwork for there to be enough doubt in the election process that a political maneuver could be brought to bear to impact the outcome,” Lakin said.