Nancy Gooch, a Black woman, was brought to Coloma from the South in 1849 by a white man who enslaved her and her husband. Gooch was soon freed when California became a state and worked as a cook and cleaned laundry for miners. She later brought her son, Andrew Monroe, from Missouri to join them in the town. The Monroe-Gooch family would become one of the most prosperous Black landowners in California.

“We have to bring forth the truth, because that’s reconciliation,” said Jonathan Burgess, a Sacramento resident who co-owns a barbecue catering business, and who also is claiming land in Coloma was that of his descendants. “And then once we bring forth the truth, which I’ve been doing in speaking the whole time, we’ve got to make it right.”

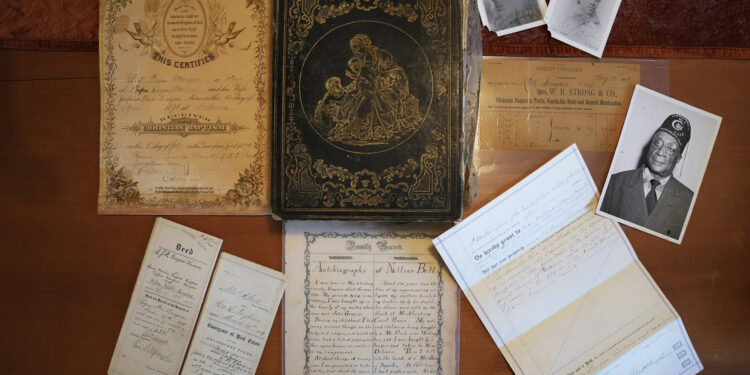

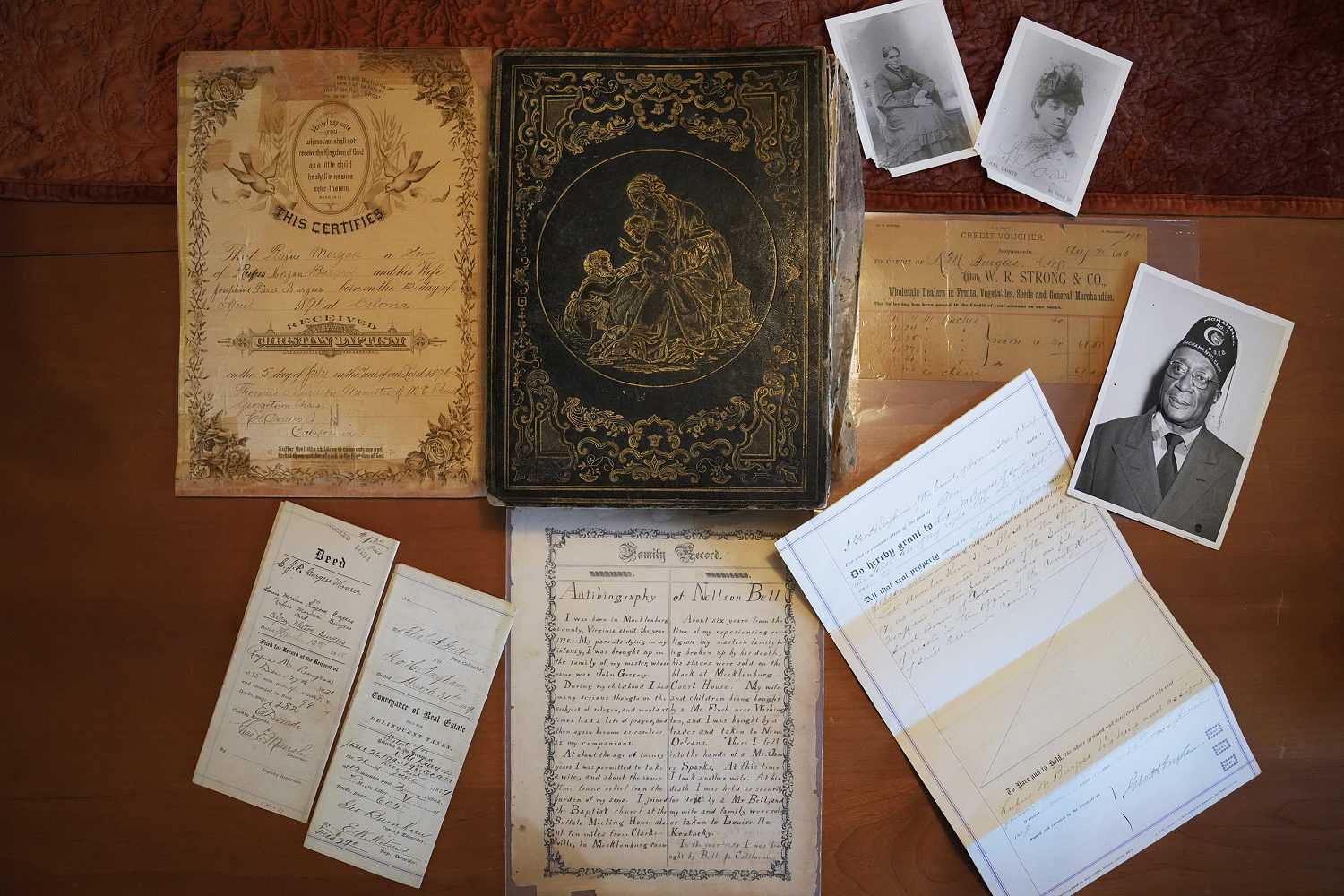

Making it right would mean compensating families for land that can’t be returned or returning property where possible, Burgess said in an interview at the park. He said he is descended from Rufus Morgan Burgess, a Black writer who was brought to Coloma with his father, who was enslaved.

Jonathan Burgess also said his family is descended from Bell, but the Fonza and Burgess families say they are not related to each other. The discrepancy highlights the difficult work that could be ahead for Black residents if California ever passes reparations legislation requiring families to document their lineage.

Cheryl Austin, a retiree living in Sacramento, said she is an heir of John A. Wilson and Phoebe Wilson, a free, married Black couple who came to Coloma during the late 1850s. After John and Phoebe Wilson died, their property was sold through probate, Austin said. The state must somehow repair harm done to families whose property was seized, she said.