Last May, Cathy Kott, a resident of rural north Georgia, received a text from an unknown number. “We’re looking for Democrats who would be willing to run against State Representative Jason Ridley,” the message read. “If you’re interested or know anybody who is, call me.”

The sender was Bob Herndon, a longtime political operative in Georgia. Herndon had been involved in recruiting Democrats to run for office for years—efforts he says were often chaotic and generally too little, too late.

“We are asking people, literally, to go into a losing battle.”

Herndon decided to do something about it after the 2020 elections, when President Joe Biden won Georgia by the slimmest of margins and the state sent two Democratic senators to Washington—and Herndon realized that Democrats running unwinnable local races could help the party in higher-profile contests. It’s a theory called ‘reverse coattails’—rather than the top of the ticket driving turnout, local races help bring voters to the polls, to the benefit of the presidential nominee or statewide candidates.

There’s data to back up the strategy. Run for Something, a national organization which supports grassroots progressive candidates, analyzed precinct-level election returns in eight states and found that President Joe Biden did better in 2020 in conservative districts where a local Democrat was running than in districts where a Republican ran unopposed. The difference was small—a boost of .4 to 2.3 percent—but in tight races, accumulated statewide across a range of districts, that amount could make the difference. The report singled out Georgia as a place where such long shot campaigns in rural red areas might have put Biden over the top.

Herndon saw the study when it came out in 2021 and took note, and last spring, he and a friend, Pam Woodley, took it upon themselves to recruit candidates with help from Peach Power PAC, a group where both were then-board members that also supports down ballot Georgia Democrats. The most effective method of outreach, they found, was sending texts. Thousands of them, to lists of likely Democratic voters living in districts where the Republican state House representative would otherwise go unchallenged. It was a recruitment operation of “brute force,” Herndon recalls.

“It’s hard to talk people into running,” Herndon says. “Why should you run in a race that you’re not going to win? And you’re not going to get any support. People aren’t going to give you money.” In conversations with potential candidates, he gave them three reasons: Give Democrats in red districts someone to vote for, force Republicans to spend money on these races, and earn enough extra votes to tip the state for Democrats at the top of the ticket.

“They are making a huge sacrifice for Democrats in Georgia,” Woodley explains, even if some of their recruited candidates are having fun. “All they are getting out of it is they are bringing more Democrats to the polls.”

When Herndon reached Kott, his timing was fortuitous. Kott was still reeling from Donald Trump’s election in 2016 and, more recently, the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling ending the right to an abortion. Georgia had quickly implemented a ban starting at six weeks gestation. After the decision, Kott said to her daughter, “I can’t believe I didn’t raise more of an activist,” to which her daughter shot back, “What about you?” The words stuck in her ears. So when Herndon texted, she did call back. Today, she’s the first Democrat to run for the state House in District 6 in over 20 years.

Georgia’s state House has 180 members, and in 2022, according to Herndon, 53 Republicans candidates ran unopposed. Herndon took that number, rounded it down, and called their effort the Fighting 50. Over about ten months, Herndon helped recruit roughly 30 candidates to run for those seats. Another dozen separately decided to run in districts where Biden won less than 40 percent of the vote in 2020, and Herndon and Woodley welcomed them into their effort.

The pair has helped the candidates navigate archaic filing paperwork, connected them with trainings and support groups, and, eventually, financial backing. On monthly zoom calls and in an active Signal chat, group members swap tips, pictures, and seek advice. Running as a Democrat where the party doesn’t have much presence can be lonely and bewildering. The Fighting 50 program not only helped get these candidates into the race, but for many, made their campaigns possible.

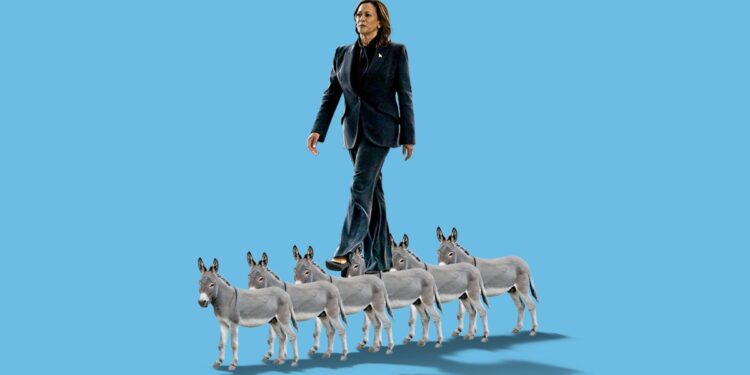

The presidential race in Georgia is neck-and-neck. The state is predicted to be one of the closest this year and could decide who wins the White House. Who takes its Electoral College votes could very well be determined by Democratic turnout in red districts where, without a local Democrat on the ticket, Democrats may otherwise stay home.

State house candidates can appeal to voters who are more invested in local issues than national races. According to Herndon, Fighting 5o members are highlighting issues important to rural Georgians, who might be upset about how Republicans legislators passed a school voucher program that is of little help in areas without private schools, or, after struggles with lacking health care, might vote for a candidate who backs expanding the state’s Medicaid program.

“If I won, I would demand a recount.”

“These candidates being out in their communities so much will bring more Democratic voters to the polls and push Harris over the top,” says Woodley. “Biden only won Georgia by 11,780 votes, so our candidates can make that difference for the statewide races.” If each of this year’s Fighting 50 candidates bring in 500 additional Democratic votes—a number Herndon hopes for—that would be 20,500 votes, almost twice the presidential margin four years ago.

“Do I expect to win?” said Jack Zibluk, a journalism professor running as a Fighting 50 candidate in House District 1, which borders Tennessee and Alabama. “If I won, I would demand a recount.”

But that doesn’t stifle his optimism. “It is an opportunity to really make a difference,” he says. “I’m 64 years old. This is a real wonderful thing I’m able to do.”

When Herndon pitched potential Fighting 50 candidates, he wanted recruits who would commit to at least two campaigns—and he expects most of their candidates to run again. “They’re learning so much in this cycle that they’ll be excellent candidates” in two years, says Herndon.

That year, he hopes the effort can help Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff win reelection. After Herndon bumped into Ossoff’s father at an event, the Ossoff campaign took an interest in the Fighting 50 . His campaign manager appeared on one of their monthly Zoom meetings. “I think [Sen. Ossoff] realizes how mutually beneficial we can be to each other,” Woodley says.

But the biggest recent boost to the Fighting 50 has come in the form of money. Originally, Herndon and Woodley ran the program as part of the Peach Power PAC, a threadbare labor of love. This summer, after recruiting had wrapped up, Woodley got an unexpected offer of $50,000 to back the project, and the two decided to strike out on their own and create the Fighting 50 PAC. Since then, they’ve raised another $80,000, mostly from a handful of large donors. It’s a small amount by political standards, but in local races, it makes a big difference.

On a recent Thursday night, Fighting 50 convened its monthly candidate video call. First came a presentation from Kimberlyn Carter, a longtime Democratic operative and CEO of Represent Georgia, which also recruits and trains candidates. The presentation was full of brass tacks: how much money they need to raise ($42 per day), which voters to target and where to find them (“I have been known to ask people for their wedding lists”), and how to write an election night speech (don’t forget your thank yous). When one candidate said the local party wouldn’t share its voter list with her, Carter knew how to pry it out (ask for it as an in-kind donation). A second speaker gave tips on how to gain an audience on TikTok (don’t only talk politics).

The Fighting 50 is intrinsically something of a longshot effort. “We are asking people, literally, to go into a losing battle,” Carter says, who explains that many districts are impossible for Democrats, thanks to gerrymandering in the state’s rural Black Belt. But she believes that with enough effort, Georgia’s government can reflect its increasing diversity, which includes expanding Hispanic populations and the nation’s fastest growing Asian American and Pacific Islander community. Carter recalls that in 1987, Oprah Winfrey brought her brand new talk show to Forsyth County, north of Atlanta, to discuss recent white supremacist protests against integrating the all-white county. A few weeks ago, she says, her friends sent her pictures of a Forsyth County Democratic Party meeting that was so full the fire marshal was called.

The candidates “understand that it’s long term work,” says Carter. “We’re asking you to run in 2024, to stay on the ground in 2025 and 2026, continuing to base build… and pushing the win margin every biannual election. Because I am a firm believer that a drop of water in the rock can make a dent.”

Kott is not likely to win her race, but she still believes she is connecting with voters on a personal level, and has earned votes by talking about north Georgia’s lacking mental health resources—an issue she says everyone struggles with. But in her conversations, one particular voter stands out. And all they exchanged was a look.

On the Fourth of July, Kott brought her 14-year old granddaughter with her to meet voters at a local celebration. She approached one couple and handed the woman a campaign flyer, which she had folded into a fan to help with the heat. But the man responded, thrusting the fan back in her hand and telling her that if she doesn’t like Marjorie Taylor Greene, the district’s Trump-aligned congresswoman, then they don’t like her.

Before the Kott walked away, she and the woman locked eyes. “I feel like we bonded in that moment,” she says, “I feel like she said to me, ‘Don’t worry, I got you.’” It was, she says, the look of a woman who knows that her husband can’t control her in the voting booth.

Kott knows she could be mistaken. But walking away, she turned to her granddaughter and said, “She’s gonna vote for me.” Her granddaughter agreed. “I think so. He was mean.”