When George Hocker underwent a grueling training course to become a CIA spy, much of America was still segregated. That meant Hocker, as a Black man, could not go to restaurants in Virginia to meet with agency instructors playing the part of foreign informants.

Different exercises had to be developed for Hocker. “I had to have car meetings, whereas my classmates could go and have a nice meal in a restaurant,” he said.

Out of a class of 75, Hocker was the only Black person. He passed the course and went on to blaze a trail as one of the Central Intelligence Agency’s first Black clandestine officers, the first to open a CIA station abroad and the first to lead a branch inside the Directorate of Operations.

Hocker’s pioneering experience at the spy agency — along with a small number of other African Americans who joined in the 1960s — has been largely overlooked until recently, partly due to the secrecy that requires most CIA officers to serve in anonymity.

But the agency recently installed an exhibit dedicated to Hocker at its museum at CIA headquarters, and he is now writing a memoir, saying he wants to pass on the lessons he learned as a “Black spymaster” about resilience and determination.

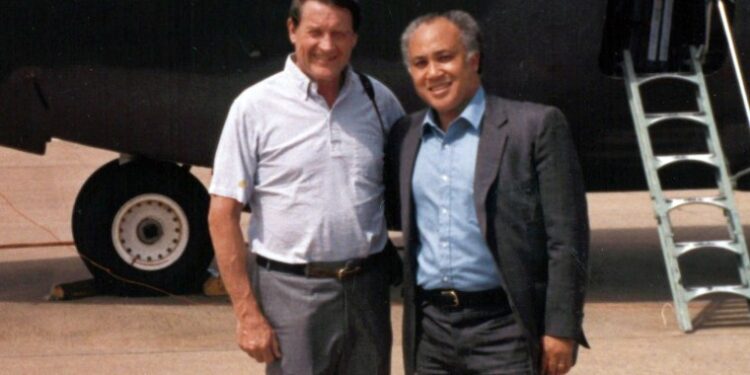

In an interview with NBC News, Hocker, 84, described the discrimination he faced throughout his career and his sometimes harrowing missions overseas.

After starting out in the CIA’s records department in 1957 while a student at Howard University in Washington, D.C., Hocker was later promoted to be an analyst at the CIA. But he was apprehensive about signing up for the spy training course.

Seeing no African American role models at the agency, he planned to leave for the Labor Department to work as economist.

“I had pretty much decided that this was not a place where I wanted to try to make a career,” he said.

Then Hocker attended the historic 1963 March on Washington, where he stood only 100 yards away as Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. He was deeply affected by what he saw and heard that day, including seeing Black and white Americans walking together peacefully, in common cause.

Hocker said it was “a defining moment for me, and I decided that I wasn’t going to let bigotry and discrimination define me, and that I was going to be a Black spy for my country.”

He then applied for the junior officer training program and was accepted. After finishing his officer training, he entered the agency’s paramilitary course, the first Black person to be accepted, which included stints in simulated “jungle” settings in various Southern states.

It was a time of strife and violent clashes in the South, with civil rights protesters facing police dogs and fire hoses. But the subject didn’t come up among his colleagues, Hocker said.

“The only Blacks I saw each day were those that were serving us food and those that cleaned up our rooms. My classmates never talked about any of those things that we would see on television when we were eating or having a beer at the end of the day, and I didn’t bring up those subjects,” he said.

As Hocker’s career as a spy got underway, he was sent to Africa for a series of tours. At his first job, in an unnamed country, the white agency officer he was replacing broke with customary practice and refused to help Hocker with his new assignment, leaving without introducing him to key contacts. Hocker had to start from scratch.

His first task was to retrieve a listening device in a foreign embassy that was no longer producing a signal, and his CIA bosses were worried that a U.S. adversary may have gotten hold of it.

Hocker conducted surveillance of the building where the device had been planted and went with a colleague to retrieve it from a janitorial room. But just as they were about to grab it, the building’s security guard asked them what they were doing there.

Hocker pointed to his camera and said he was a photographer and writer with a magazine trying to find a “good angle” to take a picture of the city through a window. He asked the security guard for his opinion and to pose for a few photos.

The security guard was delighted to help Hocker. “I had him move from one place to the other while I signaled my compatriots to go in and get the equipment,” he said.

He won praise for getting the device back and went on to other postings in Africa as the U.S. and the Soviet Union vied for influence on the continent.

In a tense Cold War moment in the late 1970s, Hocker was tapped to organize the emergency escape of a KGB spy who had valuable insights for U.S. intelligence. After a planned dead drop went wrong, Hocker had orders to arrange an urgent “exfiltration” of the Soviet agent, setting up a flight with a cover story and selecting a rendezvous spot at an out-of-the-way landing strip in a West African country, which he still is not allowed to name.

During a nerve-wracking wait for the plane to arrive for the clandestine rescue, Hocker, the KGB spy and other CIA colleagues sat in the dark in a vehicle near the runway. Hocker, sitting behind the wheel, warned the group to stay silent until the plane arrived.

As dawn broke, the plane appeared and the KGB defector was rushed on board. The Russian bid goodbye to Hocker, kissing him on each cheek and hugging him in gratitude.

Just as the plane reached about 600 feet, the local police drove up. They asked about the aircraft that had just taken off.

“I explained to them that I had an American who had been bitten by a bat. I was concerned that he might have rabies, and we needed to get him to medical treatment right away,” Hocker said. He told the police that senior officials in their government had approved the flight and the police were satisfied and drove off.

Hocker made it back home that morning. The next day he had a regularly scheduled tennis doubles match with a Western diplomat and two Russian diplomats who were really KGB officers. But Hocker had developed an unusually severe case of the hiccups during the stressful operation and was worried it might make the Russians suspicious.

He got a shot from a doctor for the hiccups, and he showed up to the tennis match looking relaxed. The Russians had no idea what Hocker had been up to over the past 48 hours.

Hocker and his tennis partner won the match.

Afterward, Hocker expected recognition and a possible medal for the successful and unprecedented operation. “But all I got was a very weak ‘great job.’ And I didn’t hear any more about it,” he said.

Despite his consistent successes, he said promotions or other professional opportunities often were inexplicably slow compared to his white colleagues.

As he wrapped up a series of tours in Africa, including setting up a new CIA station in an African country, headquarters offered him a job in the U.S. as an instructor training new recruits. Hocker politely but firmly declined, saying it was time for a job in management.

The agency offered him two other jobs that his superiors touted as vital to national security. But each time, Hocker made clear that after multiple tours abroad, he needed experience as a manager.

On the fourth try, he succeeded. Hocker was informed that he would be appointed to oversee intelligence gathering on Soviet and East European operations in Latin America, the first Black director of a branch in the Directorate of Operations.

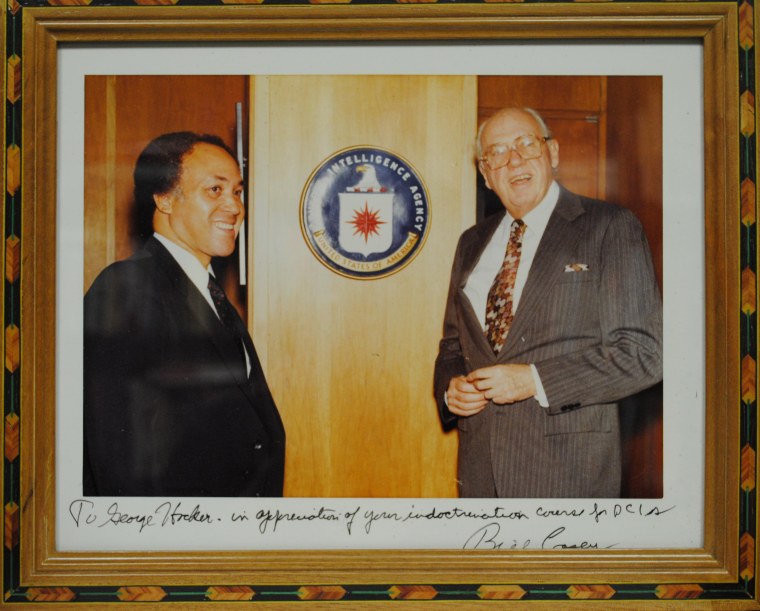

In less than two years, during the Carter administration, Hocker was selected to work as a special assistant to the director of the CIA at the time, Stansfield Turner, becoming the first African American to serve at that level.

Hocker was in the room for historic deliberations on secret missions, including the failed attempt by President Jimmy Carter’s administration to rescue American hostages held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran. He stayed on as a special assistant to Turner’s successor as CIA chief, William Casey, in the Reagan administration.

The spy agency has moved on from the days when it was dominated almost exclusively by white male graduates of Ivy League schools, Hocker said, and CIA’s leaders now grasp the importance of hiring people with different racial, ethnic, religious or educational backgrounds. But there is still work to be done, he said.

“I believe that progress is being made,” Hocker said. “It’s slow everywhere, but I think the agency recognizes the importance of having a diverse workforce, not only in terms of color, but also in terms of experiences and resilience and ability to move in different environments.”

Barry McManus, who joined the CIA in 1977 and later became the first Black chief interrogator and polygrapher, said promoting diversity remains a work in progress at the agency — and at other organizations. But Hocker was a role model for others coming up, he said.

“I think the thing I learned from him the most was tenacity and persistence and having drive. And if you have that drive and determination, then things would sort of go your way,” he said.

During one of Hocker’s early tours in Africa, a person he knew to be a Soviet spy tried to probe him about his feelings as an American facing racial discrimination back home.

The Soviet said, “You Black Americans have a lot of problems in your country. How does that affect you?”

Hocker said he was determined to send a clear signal to the Soviet agent that he was not open to being recruited. Hocker said he replied, “‘Well, you know, we do have a lot of problems, but we’re working on them as a nation. And we’re going to be all right.’”