SOURCE-SEINE — In Source-Seine, a rural village of just 72 voters in Côte d’Or in northeast France, there are no candidates running in support of President Emmanuel Macron.

Sophie Louet, mayor of Source-Seine, says candidates representing Macron-style centrists are nowhere to be seen in the tiny hamlet — an extreme example of a trend occurring throughout the country, the world’s seventh-largest economy.

“Far right, far left … and between them nothing,” she said, speaking of the four candidates on the ballot for the region in the first round of elections, which are being held on Sunday. “It’s very destabilizing. In the last legislative elections, there were 30 candidates of all stripes.”

France faces a stark choice in its upcoming election, with a leading pollster showing the far-right National Rally ahead with 36% of the vote, followed by the leftist New Popular Front coalition at 29%. Macron’s coalition trails at third with 19.5%, according to Ipsos. The surge in the right and the collapse of the center is sending shock waves across France, with some analysts warning that the deep disillusionment underpinning these numbers goes beyond France.

Macron called the snap election a day after his party was crushed by the far right during June’s European parliamentary elections. His decision was widely seen as an attempt to spook voters away from the political extremes, but a lightning-fast, three-week campaign has failed to turn the tide.

“The center has imploded,” said Samantha de Bendern, a geopolitical commentator for the news outlet La Chaine Info. “Macron miscalculated. He was hoping the moderate left and moderate right would both come to him. Instead, they’ve both joined the extremes.

“We are in uncharted territory. We are jumping off the cliff and we don’t know if our parachute is working, or even if we have a parachute,” she said.

National Rally, also known by its French acronym RN, is led by Marine Le Pen, who has softened her party’s image in recent years by abandoning hostility toward the NATO alliance and the idea of a French exit from the European Union. Her party remains committed to its central doctrine of “France for the French,” giving citizens priority over nonnationals for jobs, housing and social welfare.

Originally called the National Front, the party’s founding president, Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s father, was openly racist and convicted multiple times of making antisemitic comments and dismissing the Holocaust as a “detail” of history. Even as Marine Le Pen tried to steer the party away from its most extreme positions, RN has maintained an anti-immigration stance with strong Islamophobic undertones that it has tied to issues of order and security. Some members of RN continue to express racist, antisemitic or homophobic views, and according to a report published Thursday by the French National Consultative Commission on Human Rights, 54 percent of National Rally supporters described themselves as racist.

A ‘difficult’ choice

Emmanuel Delaval, who has lived in Source-Seine for 50 years, says people are “much more ready” to say they will vote far right. “The RN have changed considerably, it’s no longer the National Front,” he says. “That’s not to say I am voting for them.

“The choice is very, very, very difficult,” he said.

His friend, Dmitry Fouks, from the neighboring village of Trouhaut, is less coy about his feelings. “People don’t believe in politics anymore, they don’t believe in France, and they certainly don’t believe in Europe,” he says.

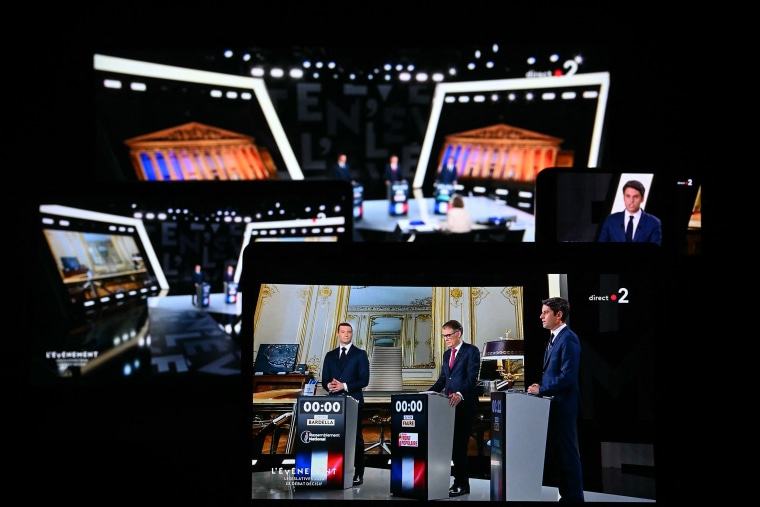

Jordan Bardella, a clean-cut, media-savvy 28-year-old and loyal Le Pen protégé who was elected president of National Rally in 2022, would be poised to become prime minister should the party secure enough seats. Bardella has promised to crack down on migration and, in a speech Monday, said among his priorities was to “put France back on its feet” by introducing what he called “a necessary law against Islamist ideologies.”

In 2022, Le Pen called the hijab a “uniform of totalitarian ideology,” saying she would like to ban the Muslim headscarf from all public places

“One of the main drivers of the vote is identity, the feeling that French people don’t recognize their own face anymore, don’t dress as they used to,” said Sebastien Maillard, an associate fellow at the U.K. think tank Chatham House, noting that France has among the largest Muslim and Jewish communities in the European Union.

“Also, there’s an element of ‘Why don’t we give it a try.’” Maillard said of the tilt toward the far right. “They’re not as scary as they used to be.”

National Rally has also proposed measures aimed at benefiting the working class. Bardella, who was raised in a disadvantaged suburb of Paris, touts his working-class roots, resonating with voters struggling with rising prices and perceptions of inequality between cities, which have benefited from Macron’s pro-business agenda, and the areas outside them, which have not. Bardella has said he will reverse Macron’s pension reform and reinstate a tax on financial wealth abolished by the president, while slashing taxes on energy and fuel.

Antoine Hoareau is a member of the Socialist Party and serves as deputy mayor of Dijon, a city 25 miles from Source-Seine. But he grew up in the village, where his uncle and cousins still live, and where he owns a home.

“There is a real divide between the cities and the towns outside,” Hoareau says. “There is no immigration here, to buy bread you have to go 10 kilometers. There are no doctors. No public transport. These are low income families that live here. It’s a social problem.

“They are watching right wing channels and they really play up immigration and crime and people watch and think there is a big problem even though there is no problem with that here.”

Follow the Seine from its source northwest to the sprawling city of Paris, and Anne Hidalgo, mayor of the capital and also a member of the Socialist Party, says she fears for her country’s future in the face of such extremism, calling Le Pen a huge risk for the country.

“People in France say we don’t have experience with these people, but we had the experience. We had the experience during the Second World War. … It is a very, very big risk for democracy, for minorities, for women,” she told NBC News. (During World War II, France’s Vichy government collaborated with the Nazis.)

With National Rally widely expected to fall short of the 279 seats required for a majority, a hung Parliament appears the most likely outcome for France, setting up the possibility of political paralysis and damaging inaction.

“Either we have no government, a technocratic government, or we haggle for months over who should be prime minister,” added de Bendern. “A year and one day after the dissolution of Parliament, Macron can call new parliamentary elections, so we will have a year of chaos.”

“We could be going into the Olympics without a prime minister,” she added.

How such political instability may affect the Olympics, which begin in Paris less than three weeks after the vote, appears to be another error in Macron’s timing.

Security concerns are already heightened across Europe amid the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and a spate of politically motivated attacks. In May, a man in southern France was arrested over a plan to attack a soccer stadium that will be used during the Olympics. Security has already ramped upin the capital, with some metro stations closed.

Macron’s Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin has said that French authorities are working on the assumption that violent protests could take place following both the first and second rounds of elections (June 30 and July 7). “It’s possible that there will be extremely strong tensions,” Darmanin told RTL radio, adding that authorities were preparing for a “highly inflammable” situation.

That tension is exacerbated by ourside outsiders targeting French voters. A report by Recorded Future’s Insikt Group, which examines trends in malware evolution, has said the French elections continue to be targeted by operations linked to Russia and Iran. These operations include cloned impersonations of French media organizations.

Also included were eurosceptic and populist political positions, dissuading support for Ukraine by amplifying skepticism towards Western alliances, while praising the RN for its willingness to engage in a dialogue with Russia to end the war. Before the invasion, RN maintained close ties with Russia, and Bardella said in a debate last week that RN would continue to support Ukraine, but would not send long-range missiles or French troops.

The report said that the overall effect of the disinformation campaigns on French public opinion has been “negligible” due to minimal online engagement.

While the Olympics are ordinarily a unifying celebration of diversity, they may well take place under an overtly xenophobic government, or no government at all.

With his presidential term running until 2027, Macron is not on the ballot. Still, the parliamentary elections will serve as a referendum on his pro-business, centrist vision of France. A supporter of assertive French foreign policy, he’s been a strong backer of Ukraine in its war against the Russian invasion.

He told the podcast “Generation Do It Yourself” on Tuesday that both left- and right-wing parties risked bringing “civil war” to France in another bid to scare voters back to the center.

He has said that he would stay in office until his term ends, regardless of the outcome of the election, but all signs point toward either a tense power-sharing arrangement with a prime minister from an opposing, likely antagonistic party, or a government without a stable majority.

“Macron is gambling France,” Maillard said. “He’s saying to the people, ‘You may have voted for the far right in the European elections, but this is for real.’ But that’s a dangerous gamble, because maybe the French will say, ‘Yes, we really do want this.’”