In the years before the Supreme Court ended the federal right to abortion, Florida’s 55 reproductive health care clinics were a critical part of the national abortion infrastructure, caring for tens of thousands of women annually from across the state and the South. Now, with Florida’s six-week abortion ban, the number of clinician-provided abortions in the state has plunged, while the need for supportive services for pregnant people is rising. Enter maternity homes—group facilities, often operated by churches and faith-based charities, that provide shelter, food, and other assistance to pregnant women, new mothers, and babies.

According to the anti-abortion behemoth Heartbeat International, the number of maternity homes has jumped nearly 40 percent in the past two years. Today there are more than 450 throughout the United States, at least 27 in Florida alone. The homes provide much-needed help to women and teens in desperate straits, including victims of abuse, people struggling with substance use problems, and kids aging out of the foster care system. But as Reveal’s Laura Morel reports in a blockbuster story with the New York Times, Florida allows most of those maternity homes to operate “without state standards or state oversight,” even as many of them impose “strict conditions that limit [women’s] communications, their financial decisions, and even their movements.”

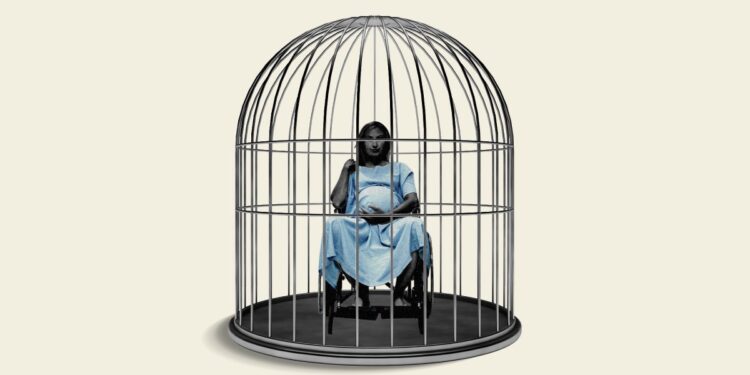

Florida allows most of those maternity homes to operate “without state standards or state oversight,” even as many of them impose “strict conditions that limit [women’s] communications, their financial decisions, and even their movements.”

The result, one woman told Morel, can be “dehumanizing, almost like we were criminals, not single mothers.”

Among the restrictions Morel found at various homes? Requiring residents to attend morning prayer and to obtain permission before leaving the premises, confiscating their phones at night, compelling them to obtain a pastor’s approval to have romantic relationships, and ordering them to hand over their food stamps to pay for communal groceries.

Morel has spent the past six months examining maternity homes as part of a Local Investigations Fellowship with the Times—interviewing almost 50 current and former residents, employees, and volunteers; reviewing homes’ written policies; and poring through more than 500 pages of police records. Her story focuses on 17 maternity homes across Florida, where she is based. Eight of the homes Morel scrutinized “routinely called the police when residents defied rules or employees,” she wrote. One home required women to install a tracking app on their phones.

As Morel notes, maternity homes—“institutions where unmarried pregnant women could give birth in secret and put their babies up for adoption”—were common for decades. Most shut down in the 1970s, but the concept is undergoing a revival in the post–Roe v. Wade era:

Homes today typically focus on keeping mothers and babies together. Many let expectant mothers, and occasionally women with children, stay for free so they can save money and find a permanent place to live. Women often learn about them through social services providers or anti-abortion pregnancy centers, and move in voluntarily.

In response to Morel’s findings, some maternity home directors said the strict rules were necessary to maintain order and keep residents away from drug users or people who might be abusive. The Florida Association of Christian Child Caring Agencies, a nonprofit to which many of the homes belong, said the restrictions were meant to “help each client break the cycles of poverty and addiction to find hope and healing in Christ.”

Social services experts in Florida told Morel that maternity homes offer vital aid to women and babies in crisis. But the inconsistencies in care and oversight are troubling, said Mike Carroll, a former secretary of the Florida Department of Children and Families who now oversees a network of social services programs, including a licensed, faith-based maternity home. “It can lead to some pretty abusive situations,” Carroll told Morel.

Morel’s story appears in the New York Times and Reveal.