Not many horror films are as appallingly gruesome to make as they are to watch. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which opened 50 years ago this month, is a notable exception.

It is one of the most controversial yet enduringly influential horror movies in cinematic history, which despite its starkly unsubtle title was described in the New York Times as ‘a formally exquisite art film, packed full of gorgeously nightmarish images as poetic as they are deranged’.

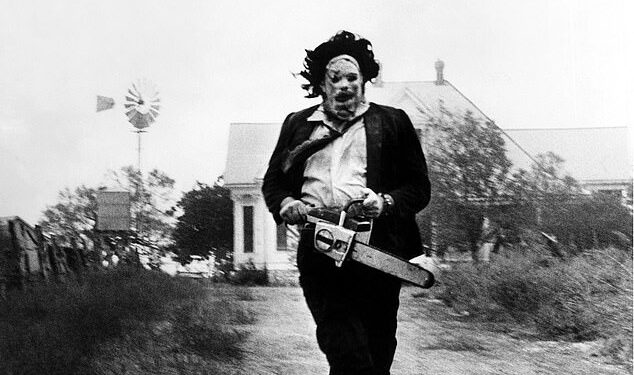

Yet it was shot at the height of an oppressively hot Texan summer in such ‘intolerably putrid’ conditions that the Icelandic-born actor Gunnar Hansen, who played the story’s depraved villain ‘Leatherface’, later claimed he wasn’t sure whether the cast would get out alive.

Leatherface, a psychopathic masked cannibal who liked to torture his victims before killing and eating them, was truly the stuff of nightmares. But so was the set – a farmhouse in Round Rock, Texas, in which the temperature consistently soared above 110F (43C).

Gunnar Hansen created Leatherface the chainsaw-wielding maniac in 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Actress Marilyn Burns pictured as Sally Hardesty, in a scene from 1974 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre film

And, to make conditions even more uncomfortable, director Tobe Hooper insisted on littering the building with dead dogs, cattle remains and fetid cheese. It wouldn’t, couldn’t, possibly happen now. Arguably, it shouldn’t have happened then.

But Hooper reasoned that a terrible stench would help to create a horrific atmosphere, making the ghastliness of the plot seem all the more real. As a result, the actors kept having to dash outside for ‘vomit breaks’.

All this was conceived in an Austin department store shortly before Christmas 1972. Not yet 30, Hooper had popped in to do some shopping and found himself in the crowded hardware section, desperate to escape. ‘Those big crowds have always gotten to me,’ he told the Austin Chronicle decades later. Then he noticed an array of gleaming chain saws.

He fantasised about seizing one, setting it off, and hacking a deadly path through the Christmas shoppers. Within less than a minute, he liked to claim, his idle fantasy mutated into a coherent idea: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was born.

There were other inspirations. America at the end of 1972 was an unhappy country. The Watergate crisis was fermenting, the Vietnam War continued to rage, and the political assassinations of the 1960s loomed large in the collective memory, as did the murderous 1969 rampage by disciples of Charles Manson.

Moreover, just nine months before Manson’s acolytes slaughtered actress Sharon Tate and six others, a former odd-job man called Ed Gein – known as the Plainfield Butcher – went on trial for numerous crimes including murder and body-snatching.

Gein had been fascinated by the wartime story of Ilse Koch, whose husband was the commandant of Buchenwald concentration camp, and who allegedly fashioned lampshades from the tattooed skin of murdered inmates. Duly inspired, he exhumed corpses from the cemetery in Plainfield, Wisconsin, making keepsakes from their skin and bones. Leatherface, whose mask was crafted from human skin, was modelled on Gein, who was held in a secure psychiatric hospital by the time Hooper dreamt up The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

But some of the worst serial killers in the nation’s history were still at large. Among them was 6ft 9in Edmund Kemper, who had been jailed for murdering his grandparents in 1964.

‘I just wanted to see what it felt like to kill Grandma,’ he told police.

Working on the script with his co-writer Kim Henkel, Hooper had also kept a keen eye on a case closer to home, the so-called Candy Man Murders, in and around Houston, Texas.

Hansen was 26 when he was cast in the role in part for his height; he was six feet four inches tall. The film – and the character of Leatherface – became an instant fan favorite

Hansen once said that Leatherface wore masks because there was nothing behind the mask. ‘Killing was the only thing he knew,’ he said of the character he brought to life on screen

An outwardly respectable man called Dean Corll, abducted, raped, tortured and killed at least 28 boys and young men before he was shot by his own warped accomplice in August 1973.

There was one other notably macabre influence on Hooper. Just before Christmas 1972, he learned, with the rest of the world, that 16 survivors of a plane crash 72 days earlier in the Andes had been found. To stay alive, they had been forced to eat the flesh of those who had died.

That grisly detail helped to sharpen Hooper’s vision of a modern version of Hansel and Gretel, the 19th-century German fairy tale by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

Hansel and Gretel are brother and sister, abandoned in the woods by their mother, who are captured by a cannibalistic witch. Hooper envisaged his film’s young protagonists similarly wandering off the beaten track into the same kind of dreadful peril but perhaps without such a happy ending.

Long before this, Hooper had himself almost become the victim of mass murder. On August 1, 1966, he was wandering across the Austin campus of the University of Texas when a police officer yelled at him to take cover in a nearby building. Someone was shooting people from the 28th floor of the university’s Administration Building. Seconds later, a bullet struck the same cop.

The shooter was former Marine Charles Whitman, the ‘Texas Tower Sniper’, who had already fatally stabbed his mother and wife that day, then gunned down 14 more in a 96-minute killing spree. The long-haired Hooper, then just 23 years old, watched as much of this unfolded. He claimed to be a laid-back hippie, but was profoundly affected by the Whitman massacre. For him, it was the most alarmingly personal of those 1960s events entirely at odds with the counter-cultural cliches of peace and love.

So, all things considered, it’s not surprising that he conceived The Texas Chain Saw Massacre how and when he did, and why the Hansel and Gretel theme so appealed to him.

By then, he and Henkel had already made one film, Eggshells, a largely improvised 1969 drama about a commune of hippies haunted by a malevolent spirit. That summed up what both filmmakers had come to feel about the 1960s. But their second project together was very different.

The film began shooting on July 15, 1973, but there were already troubling portents of headaches to come. Instead of showing up on set, Gunnar Hansen went on a drunken bender and locked himself in his hotel room with a debilitating case of pre-shoot jitters. Had he known what was in store, he might never have emerged.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre tells the story of five teenage friends on a road trip, who make the fatal mistake of calling at a remote house in the hope of getting petrol for their van.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre follows a group of friends who travel to rural Texas and find a remote house, not realising it’s the property of a family of deranged killers

It turns out to be home to Leatherface and his maniacal relatives. In the film’s most notorious scene, one of the teenagers, Sally Hardesty (played by Marilyn Burns), is tortured at the family dinner table. She is tied to the arms of a corpse, and Leatherface cuts her finger so that the 100-year-old patriarch (in fact played by teen actor John Dugan in heavy prosthetics) can drink her blood.

Most self-respecting horror- movie fans revere that scene. But what they don’t all know is that the horror was real. Hansen used a prop knife which had a tube of fake blood attached to it, but it malfunctioned.

After numerous takes he decided to take matters, all too literally, into his own hands. He surreptitiously cut Burns’ finger for real, which in the heat of filming none of the other actors realised. Burns was said to be furious when she found out. But not Dugan, who didn’t discover ‘until years later I was actually sucking on her blood, which is kind of erotic, really’.

In 2013, two years before he died, Hansen wrote a memoir called Chain Saw Confidential, for which he interviewed Burns. She told him there had been nothing fake about her fear. ‘You scared me to death,’ she said. The way he leered at her, she recalled, felt ‘too real’.

An actor called Jim Siedow, playing another of Leatherface’s bloodthirsty clan, found it hard to work himself up to the point of simulating extreme violence against Burns. So Hooper and the rest of the crew egged him on, screaming ‘hit her, hit her harder, hit her some more!’ Even Burns joined in. ‘Hit me, don’t worry about it,’ she said.

Such ploys are unthinkable today, while any director littering a set with dead dogs just to create a noxious atmosphere would be fired, and cancelled. But in his 2019 book The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: The Film That Terrified A Rattled Nation, author Joseph Lanza singles out another possible reason for what even at the time was unhinged behaviour: cannabis. Outside the house where filming took place, there was a two-acre plot of cannabis. Hooper, his cast and crew were told that, as long as they were discreet about the ‘extra-curricular gardening’, they could help themselves.

However much he consumed, Hooper is no longer around to answer for his actions; he died in 2017, aged 74. But he took great satisfaction from the lasting influence of his most famous film, which directly inspired a raft of later pictures, from John Carpenter’s 1978 hit Halloween to Ridley Scott’s Alien a year later.

It also established power tools as weapons of murder and torture, which won’t sound like much of a legacy to everyone … but horror fans know otherwise.