Erlin Centeno’s family has feared being permanently separated since the father of three children was detained four months ago following a routine check-in with immigration authorities in New York City.

The lives of Centeno and his family were endangered after four of his cousins were killed and he started receiving many letters and text messages containing death threats, according to court transcripts obtained by NBC News of his testimony to an immigration judge. The threats were a result of the work he and his cousins did defending the territorial rights of Afro Indigenous communities in his homeland known as Garifuna, according to Centeno and his wife.

The emotional toll of Centeno’s detention was weighing heavily on his wife, Trini Merced Palacios, as she sat down with NBC News on June 13 to open up about her husband’s immigration plight for the first time.

“I feel very bad every time I talk about that,” the 35-year-old woman said in Spanish. Tears streamed down her face as she held her restless 2-year-old daughter, Genesis, who had not been able to sleep well since her father’s detention, according to Palacios.

Sometimes, when Genesis seems to be asleep, she suddenly wakes up, calling “papá, papá,” the mother said. “So, I tell her, ‘You’ll see Dad soon.’”

But Palacios doesn’t actually know if or when the family will be reunited.

“My fear is that they will deport him to Honduras, where he had death threats,” she said.

Centeno’s detention is igniting serious concerns from his loved ones and attorneys that he may face the same dangers he escaped from when he fled Honduras with his family in the summer of 2022 and was allowed to enter the United States in an effort to seek asylum.

However, Centeno is ineligible for asylum because of a previous deportation order. Because of this, he must undergo a different type of immigration proceeding that is more complicated, requiring him to meet a higher standard to convince immigration authorities that he will likely be harmed if deported to Honduras.

Under U.S. law, it is illegal to deport someone to their country of origin if their life would be endangered. If the immigration proceeding is successful, the person wouldn’t get asylum but would be allowed to stay in the U.S. without being deported.

Centeno wasn’t able to convince immigration authorities of his fear-based claims. Now, his family and attorneys have very limited options but they haven’t lost faith that they can try to keep him safe in the U.S.

‘They didn’t feel safe’

The Garifuna people are descendants of enslaved Africans, and also Arawak and Caribbean Indigenous communities who have historically been displaced from their ancestral lands. Many of them remain in Guatemala, Nicaragua and Belize — but most of them are in Honduras, where they face high levels of violence, racism and extreme poverty, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

Centeno started advocating for Garifuna rights in 2020, working with the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras, one of the most prominent Garifuna nonprofits in Honduras. According to an IACHR report, their members have long been harassed, threatened, beaten, kidnapped and killed amid land grabbing and territorial disputes involving industries with high economic interests in the region — which has intensified as local investors have sought to develop the area — as well as local gangs fighting over territories.

The IACHR has documented the cases of dozens of Garifuna activists who have vanished or been killed since 2019. Since at least 2015, the commission has repeatedly condemned Honduras for violating the ancestral property rights of the Garifuna people.

Palacios said her husband’s cousins are among those killed and is convinced that Centeno would have been next if the family hadn’t come to the U.S. to seek safety.

“The United States has always just been framed as a land of opportunity and safety, and they didn’t feel safe in any other places nearby in Central America and they don’t really have family anywhere else,” said Deisy Flores, a staff attorney at Make The Road New York, who is involved in Centeno’s immigration case.

‘They took a part of me’

After the family’s arrival in the U.S. two years ago, Centeno had been regularly attending routine check-in appointments with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in New York City as he was trying to find a way to remain in the country legally.

Settled in New York City, Centeno had been working in construction jobs and attending a church in New Jersey. The family’s goal was to eventually move out of the migrant shelter in which they have been living.

Palacios and their three children accompanied Centeno to one of those appointments Feb. 14. She remembers they barely slept the night before and didn’t even have breakfast that morning as they rushed to the ICE office, commuting through heavy sleet and bitter cold temperatures to make it on time.

As the hours went by and the waiting room emptied out, Palacios started feeling a sinking fear over the possibility that her husband would be detained. After all, the appointments normally take about an hour, she said.

“Those people grabbed my husband and from there, and I never saw him again,” Palacios said. “I felt like they took a part of me.”

“Erlin for me, he is a good person,” she said. “He is kind and loving to me.”

Centeno was taken into custody and sent to a detention center in rural Pennsylvania, more than a hundred miles away from his family and legal team.

Palacios said she feels like “I have no one in the world” since Centeno was detained. The husband and wife have known each other their entire lives, starting out as best friends in Honduras before becoming romantic partners, ending up in marriage and family.

Neither Palacios nor Centeno’s legal team at Make The Road New York know exactly why ICE decided to detain him that day.

Harold Solis, the main attorney representing Centeno in his immigration case, said nothing had changed in the man’s life that otherwise may have made him a priority for ICE to detain him.

“He had been complying with his ICE check-in requirements when he was suddenly separated from his family,” Solis said.

ICE did not respond to questions from NBC News asking why Centeno was detained Feb. 14.

An uphill battle to remain in the U.S.

Two weeks after his detention, Centeno had a reasonable fear interview with an asylum officer who determined that his claims lacked credibility. But his lawyers said the process was riddled with irregularities, including the fact that Centeno’s attorney was not notified about the interview, as well as issues with Spanish translation that made Centeno very frustrated.

These issues resulted in misunderstandings, leading to his interview being cut short, not even discussing his work as a Garifuna activist and the risks that come with that, according to Flores and Solis.

An ICE spokesperson did not respond to questions about the reasonable fear interview process, only telling NBC News in an email, “We are extremely limited to what we can say regarding asylum claims.”

A week later, Centeno and his attorney appeared before an immigration judge to review the asylum officer’s determination. His attorney brought up the irregularities and Centeno was able to elaborate on his fears based on his activism, also adding that his cousins had already been killed or kidnapped for the same reason, transcripts of the hearing obtained by NBC News show.

The immigration judge agreed with the asylum officer and found Centeno’s testimony not credible.

This outcome is common among people, who like Centeno, need to go through a reasonable fear interview to remain in the U.S. legally. Data from the U.S. Executive Office for Immigration Review shows that most immigration judges will uphold the no reasonable fear finding of the asylum officer.

Reasonable fear immigration proceedings are “relatively rare,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy director at the American Immigration Council. Only a few thousand immigrants go through the procedure every year.

It is specifically designed for people who have expressed a fear of returning to their home countries, but have a previous deportation order or have been convicted of an aggravated felony, said Lauren Reiff, associate director of the immigrant protection unit at the New York Legal Assistance Group, a nonprofit providing free legal services.

This is a higher standard to have to prove than an asylum-seeker who goes through a “credible fear” process, where the likelihood of them facing danger in their home country is possible though not necessarily likely.

It is illegal for the U.S. to deport somebody to a country where they would face persecution based on a protected characteristic, such as race, religion, political affiliations or belonging to a particular social group, she said. “So, the reasonable fear process is a way to potentially avoid that.”

A deportation order from 15 years ago is what’s now complicating Centeno’s chances of remaining in the U.S. with his family. At the time, he had been found to be in the U.S. without legal documents and was deported. That deportation order was later reinstated on a few other occasions after he was found to have re-entered the U.S. seeking work and a safe place to live.

According to a court document related to one of his unauthorized re-entries in 2017, Centeno was convicted in 2009 in Houston, Texas of “burglary of habitation,” which in the state means entering someone’s dwelling without consent with intent to commit theft. The charge is considered a felony, but not an aggravated one.

“It should not be legally relevant to the merits of his fear-based claim for relief,” Solis said.

Despite the complicated details of his case, Centeno was allowed back in the U.S. in 2022 with his family to pursue his fear-based claims as long as he kept showing up regularly to his ICE check-in appointments, allowing immigration authorities to keep tabs on him, Solis added.

Data gathered by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University suggests that those who attempt to seek asylum while in detention are significantly less likely to get relief or receive any kind of protection from deportation since detained individuals have a harder time finding an attorney and gathering the necessary documents and testimonies to sustain their claims before an immigration judge.

People undergoing a reasonable fear procedure are “almost always detained,” Reiff said. This makes it harder for them to practice “connecting the legal dots to really articulate why it is that they are at risk” before they have one shot at an interview with an asylum officer, she added.

Immigration authorities intend to reinstate Centeno’s deportation order once again based on what happened during his reasonable fear interview, immigration documents obtained by NBC News show.

What’s next?

Reiff and Reichlin-Melnick say there’s very little regal recourse within the immigration court system for someone in Centeno’s position.

His last hope is an appeal his attorneys filed in a New York federal court to fight his old deportation order, Solis said, adding that the appeal is currently on hold until the federal government decides another case later this year that could set a legal precedent relevant to Centeno’s case.

Until then, Palacios and her 10-year-old son, Keslor, are imploring ICE to let Centeno await his immigration appeal at home with his family, outside the detention center.

Keslor said he misses playing Christian songs on the guitar with his dad and having his father help him with his school homework.

Palacios said that Keslor had been losing interest in school and struggles to eat since Centeno’s detention.

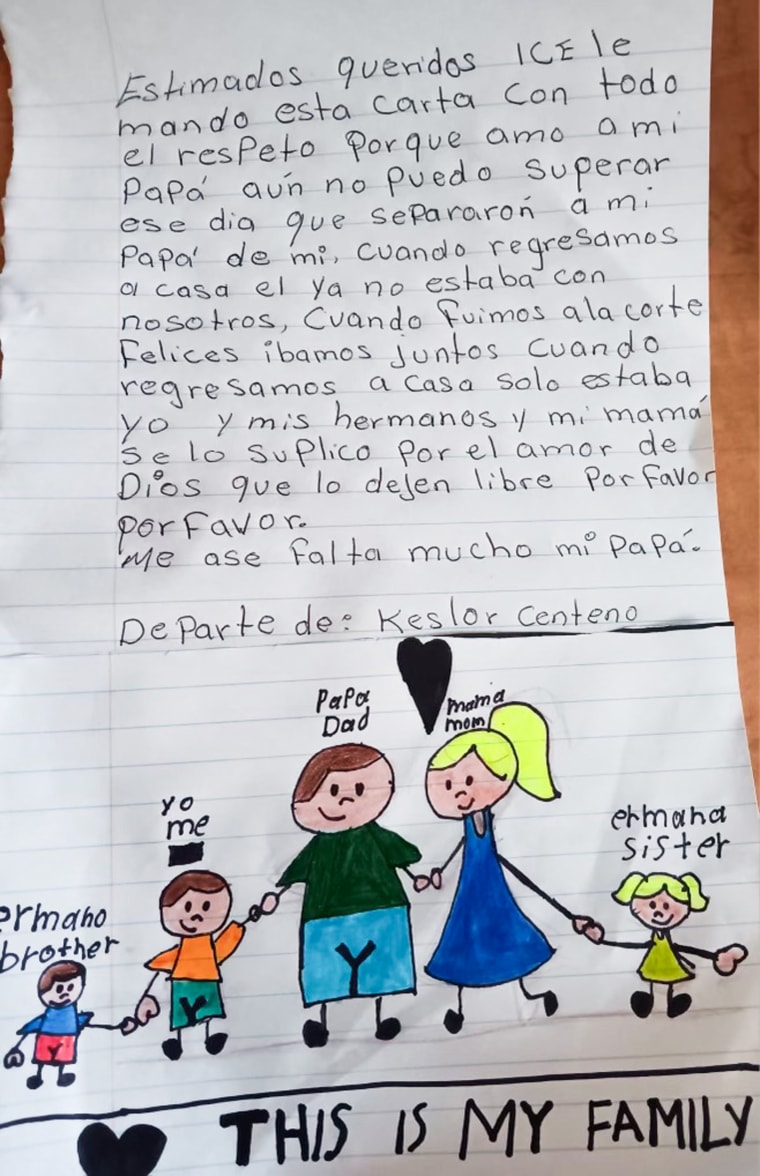

In a handwritten letter to ICE, Keslor described the sadness he felt when he witnessed his father’s detention.

“I can’t get over that day when they separated my dad from me. I beg you for the love of God to please let him free,” the child’s letter reads in Spanish. “I miss my dad very much.”

Centeno’s wife said that in Honduras, “they can kill us…just because he helped the Garifuna people.”