The news Tuesday night was a shock, mainly because of the secrecy that led up to it.

Fernando Valenzuela, 63, passed away at a Los Angeles hospital. He had been hospitalized for a month, leaving his job on the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcast team before the end of the season to tend to his health. And, to be honest, he had not looked good in the weeks leading up to his hospitalization, but the details were a closely guarded secret.

But as we mourn the passing of another franchise icon we can at least appreciate that he got his flowers, from the team and from the community, while he could enjoy them.

Valenzuela might have been the most culturally influential of any player who wore a Los Angeles Dodgers uniform, for reasons that go way beyond what he accomplished on the field.

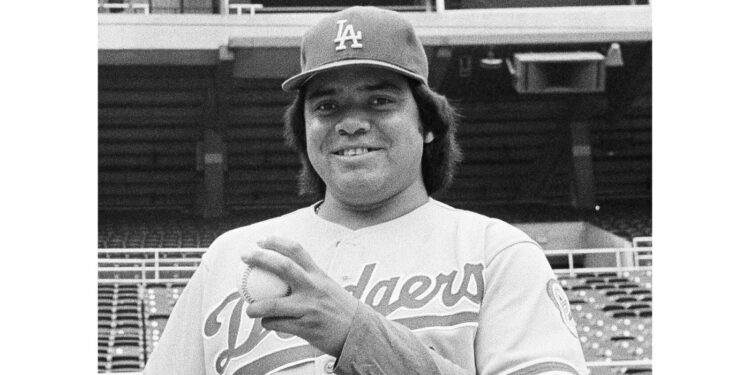

We will remember the craziness of Fernandomania, touched off in 1981 by the pudgy 19-year-old rookie who, as a substitute starting pitcher on Opening Day against Houston, shut out the Astros, 2-0 – and went on to win his first eight starts, with complete game shutouts in five of them.

We will remember a season, divided by a players’ strike, in which Valenzuela won both the National League Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards, with a 13-7 record, 2.48 ERA, 11 complete games and eight shutouts in 25 starts, and 180 strikeouts in 192⅓ innings. All of those numbers were league-leading totals.

(We’ll forget, for a moment, the chance at greatness that slipped away at the end of the 1980 season. The Dodgers rallied the final weekend to force a one-game playoff with Houston for the division title. Valenzuela, who didn’t allow a run in 17 relief innings after being called up from Double-A San Antonio, was available to start the playoff game. Instead, Manager Tom Lasorda – possibly influenced by a call from General Manager Al Campanis – went with veteran Dave Goltz, and the Dodgers lost, 7-1.)

We’ll remember Game 3 of the 1981 World Series at Dodger Stadium. Down 2-0 to the Yankees, the Dodgers started Fernando, and he delivered a 149-pitch effort, a sloppy yet magnificent 5-4 victory that started his team to four straight wins over the Yanks. As Vin Scully put it on the CBS radio broadcast, “It wasn’t his best performance, but it was his finest.”

We’ll remember the 21-victory season in 1986 and the five straight strikeouts in the All-Star Game that season, and his no-hitter in 1990 and Scully imploring us to throw our sombreros to the sky. We will remember Fernando’s unflappable nature on the mound, eyes upward to the heavens during his delivery, and the screwball that was his signature pitch.

We will also remember that Fernando became a nationwide phenomenon despite – or maybe because – his initial communication with the English-speaking world came through an interpreter, Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrín.

And there is this, most notably, and the reason for that cultural influence, as expressed by Jarrín in a 2018 interview:

“When I started with the Dodgers in 1959 at the Coliseum, the Latinos coming to the ballgames were about eight percent. Now, at Dodger Stadium, they tell me it’s around 46 percent Latinos.

“And if you go during a game and take a walk around the ballpark, you will hear as much Spanish as English. And also there’s a big change: In the early years the Latinos used to come to the bleachers and the top deck. Now you find Latinos in every level of the ballpark, including the most expensive seats. It’s really gratifying.”

Fernando was the one who, unwittingly, settled an old grudge. For years after the construction of Dodger Stadium, many Latinos in the community were unwilling to forgive Walter O’Malley for choosing Chavez Ravine, which had been a thriving Mexican-American community for decades before eviction notices were sent to residents in the early 1950s, originally to clear the land for construction of a public housing development.

That project never got off the ground, but most of the residents at the time had accepted financial settlements and left. The sight of the stragglers being removed to begin construction of the stadium seemed to put the onus on O’Malley and the Dodgers, and the animosity lasted for more than two decades. The debate hasn’t completely faded away even now, but Fernando’s presence helped melt away the resistance.

“His effect, his legacy, his impact is going to last forever,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said the day before Valenzuela’s No. 34 was retired – finally – last August.

“With what Fernandomania, Fernando Valenzuela, did for the Dodgers organization, the fan base, that certainly moved the needle and has been sustainable,” Roberts continued. “Whether it warrants the Hall of Fame, that’s not my decision. Obviously, I don’t get a vote. But you can’t debate that his impact on the organization and Major League Baseball entirely hasn’t been just as impactful alongside his statistics (as that of) anyone that’s in the Hall of Fame.”

A historic oversight was righted when Valenzuela’s number was retired, ending the club’s policy of only retiring numbers of Hall of Famers, with the lone exception of Jim Gilliam. Unofficially, No. 34 was never worn again by a Dodger after Valenzuela left, and you could say successive generations of clubhouse attendants took care of what the ballclub finally acknowledged officially.

There was some estrangement between the Dodgers and Fernando for a few years, but he returned to the club and the Spanish-language broadcast team in 2003, and all sides were better for it.

Adios, Fernando. Your impact on the team and its fan base should never be forgotten, and hopefully never will be. And with the Yankees coming to town for the first World Series meeting between the clubs since 1981, I think it’s only appropriate that clips of that 149-pitch classic be shown on the Dodger Stadium video board throughout each home game of this series.

Originally Published: