The stands in the stadium on the outskirts of Paris were packed with fans. The excitement was building.

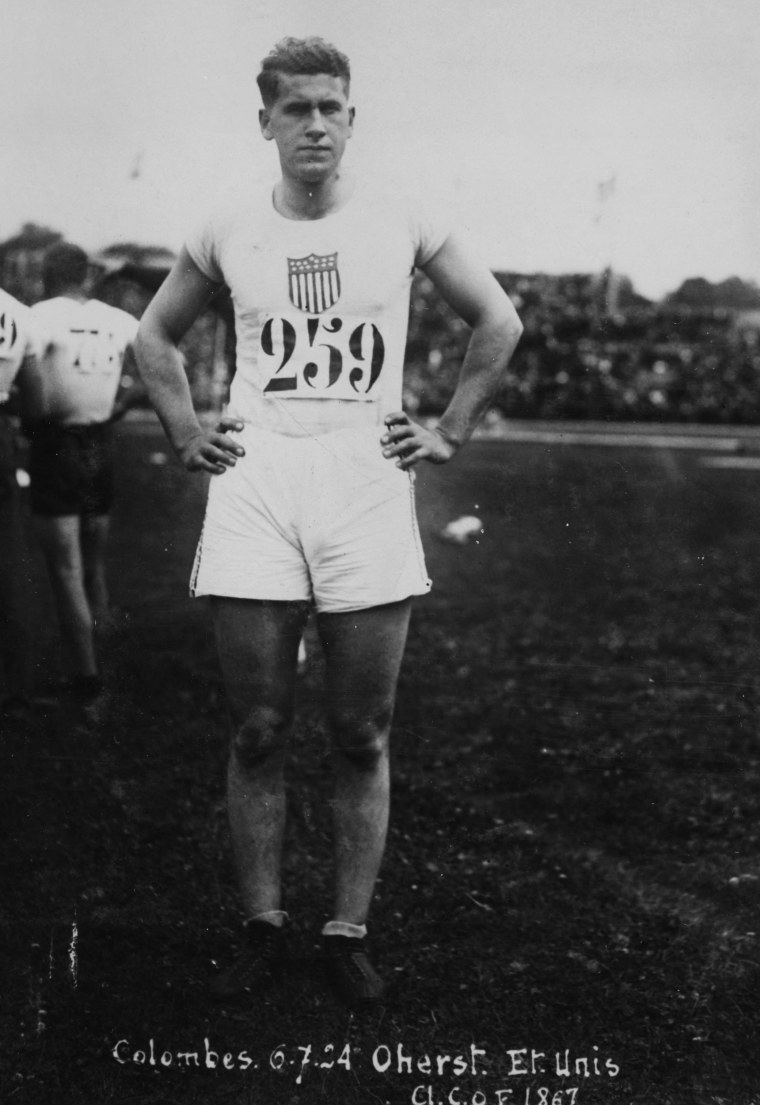

But the strapping 22-year-old American who picked up his javelin and prepared to make history had no problem tuning out the crowd at the Olympic Stadium in Colombes.

Eugene Oberst had played football for the legendary Knute Rockne at Notre Dame before he began chasing Olympic glory.

“Almost 40,000 people were in attendance, but crowds never affect me when I am in competition, so I did not pay any attention to them,” Oberst wrote in the journal he kept while competing in the 1924 Olympics.

Instead, Oberst got into the zone.

“The throwing having begun, I put on a borrowed pair of spike shoes, the first I ever wore,” Oberst wrote. “I was feeling great and on my first throw I heaved the spear out farther than any other spear had gone up to this time of the meet.”

Then the skies darkened and the rains came, “causing the ground to soften and become slippery” just as the finals were getting underway, he wrote.

The spikes Oberst had donned were no match for the mud.

“On my last two throws my feet slipped and neither of my throws were good,” he wrote.

But the 58.35-meter throw that got Oberst into the finals was enough to win him the bronze, making him the first American to medal in the javelin throw.

Oberst’s recollections from those momentous games were jotted down in a small, black leather-bound notebook that his son, Robert Oberst, retrieved and later used to write a recently published biography of his dad called “Gene ‘Kentuck’ Oberst: Olympian, All-American, Notre Dame Football Champion.”

It chronicles the often painful path that Oberst took to win an Olympic medal despite being born with deformed feet that forced him to wear specially made shoes and metal braces throughout his childhood and into college, his son said.

As for the borrowed spikes, Oberst returned them to his teammate Harry Frieda, he said.

“My father had worn spikes before, but those were football spikes, not track-and-field spikes,” Robert Oberst said.

Growing up, Robert Oberst said, he was aware that his father had competed in the Olympics, and whenever the games were on television he would retrieve his father’s bronze medal and polish it.

“That became my thing,” he said. “But as kids, we mostly weren’t all that interested in all that.”

As it happened, Oberst was an accidental Olympian.

“The story goes that my dad was walking by the track, saw a javelin lying there, and threw it so far that Rockne immediately recruited him for the track-and-field team too,” Robert Oberst said.

It wasn’t until after Oberst died in 1991 at the age of 89 that his son began piecing together the story about how his father, the youngest of 11 children from Owensboro, Kentucky, became one of the country’s most celebrated athletes after the Paris Olympics of 1924.

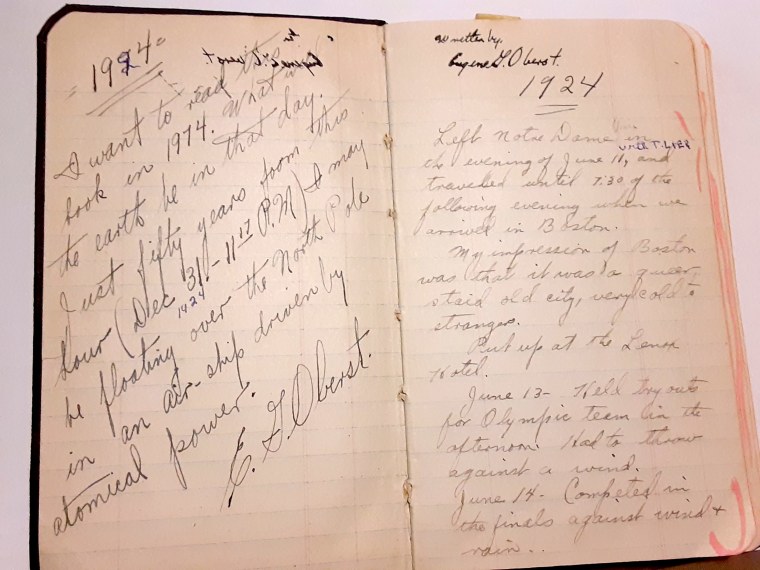

Oberst’s on-field heroics in Paris comprise only a small part of the 60-or-so-page journal that he wrote. But it clearly was an important period in his life, judging by the notes he scrawled in the opening page.

“I want to read this book in 1974,” he wrote.

Oberst devoted the first part of his account to the eight-day trans-Atlantic trip aboard the S.S. America from Hoboken, New Jersey, to France and the inventive ways the athletes used to continue training on the ship.

“We slipped anchor and steamed away from the pier,” he wrote on June 16, 1924. “The throng gathered upon the pier gave us a rousing sendoff. As the tugs were pulling us out into the harbor, the whistles of other boats, bidding us Bon Voyage, drowned out the sounds of bands playing on nearby boats.”

By today’s standards, the cabin Oberst shared with his teammates would be considered spartan. But in his journal, he described his accommodations as “beautiful and comfortable.”

“We have four beds, two below & two above in a straight line opposite the two port holes,” he wrote.

The next morning, “all the track & field men were assembled in the 3rd class lounge room,” where they met their coaches and got the uniforms they would be competing in as well as the outfits they were required to wear out in public.

“My blue serge suit was entirely too small for me,” Oberst wrote, forcing him to exchange suits with a smaller teammate. “My track pants, however, are 6 sizes too small and as yet I can’t get them exchanged.”

Then it was off to the gym, where they tossed around heavy medicine balls and ran laps on the upper decks.

They also figured out a way to practice their javelin-throwing, Oberst wrote.

“We fixed a string about the end of a javelin in such a manner that we were able to throw it overboard,” he wrote. “The end of the string we fastened to the railing. Each man took three throws. The javelin would go out into the air and fall into the water like a whaler’s harpoon.”

There were other diversions for the passengers: fine meals, movies in the evenings, sing-alongs and live skits.

“Mass upon the ocean is very inspiring,” Oberst, a devout Catholic, wrote.

But five days after leaving the U.S., “the sea grew very rough” and Oberst and several of his teammates struggled with seasickness.

By June 24, Oberst was delighted to see the lights of Cherbourg Harbor and itching to get back on dry land. But when he finally disembarked the next day, his first impressions of France were disappointing.

“I believe the whole town turned out to see us, and never before have I seen such a worn out and tired looking group of people,” he wrote. “Small boys with dirty patched clothes begged for pennies, a few of them endeavored to earn the money by pulling off stunts, such as walking on their hands and standing on their head.”

Paris did not impress him much at first, either. “From the auto Paris looked very old,” he wrote.

But it grew on him.

“I have seen many points of interest and learned to like Paris better than I did upon first entering it,” he wrote.

In particular, Oberst admired the stunning architecture of France’s churches and was awed by the palace at Versailles. “I felt as if I was in paradise,” he wrote.

Oberst, his journal reveals, did a lot of sightseeing, a bit of shopping, and got to meet Hollywood screen stars like Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, then known as “America’s Sweetheart,” who were in Paris for the games.

“Mary Pickford and Doug Fairbanks both appeared to me to be smaller than I had before pictured them,” he wrote. “They are a very pleasant couple, and ‘tis no wonder they are so well liked.”

Oberst was ready to compete when he arrived on July 6, 1924, at the stadium in Colombes. He wrote that he was surprised to finish in the top three.

“I was very satisfied with the result since we Americans were not expected to place in the javelin throw,” he wrote. “I had no idea that I would secure a place. I entered the meet in a care free way intending to throw the best I could.”

The day after his medal-winning performance, Oberst wrote that he returned to the stadium and watched British runner Harold Abrahams win the 100-meter dash, an accomplishment that was depicted in the 1981 Oscar-winning movie “Chariots of Fire.”

On July 28, 1924, Oberst wrote he was back on the S.S. America and bound for New York City to attend a ticker tape parade up Broadway. And this time, he received a medal of a different color.

“Landed at New York on August 6th,” he wrote. “Marched up Broadway to City Hall & was presented a fine gold medal by Mayor [John] Hylan.”