BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonOn a Sunday morning in September, the air inside the historic Mt Lebanon AME Zion Church was filled with the sounds of gospel music, prayer – and politics.

“This is a… very, very important, very, very dangerous opportunity,” Reverend Javan Leach said.

“The reason why I say dangerous: because if we don’t participate with our voice, and our body, that’s just like casting a vote for the other side.”

“Amen,” the congregation shouted.

Located in Pasquotank County, where a third of the population is black, the church is in a rare Democratic stronghold on North Carolina’s north-east coast.

It was rural black voters, like those at Mt Lebanon church, who were credited with helping Barack Obama take the state in 2008, the only time a Democrat has won North Carolina since the 1970s. Donald Trump took the state in both 2016 and 2020.

But support for Democrats has been declining in Pasquotank, just as it has been in other rural areas across the country over the past few years. In 2020, Democrat Joe Biden won the county by just 62 votes – the party’s slimmest margin yet – barely bigger than Sunday’s congregation.

Trump beat Biden in the state by 1.3% in 2020, but polls now rate it as a “toss-up” between him and Kamala Harris, giving Democrats fresh hope in a state where losing has been the norm.

With margins razor-thin in not just North Carolina, but other battleground states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan, Harris’s campaign will have to excite Democratic voters from across all corners of the state – not just the blue urban areas, but the deep-red countryside, too.

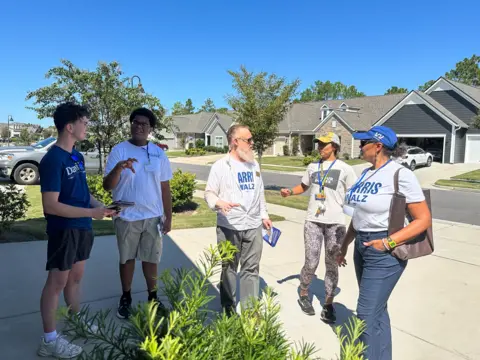

BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonTo do that, they’ve opened offices in places where Democrats have usually not campaigned but where strategists see new potential. The goal is to churn out as many votes as possible in the least likely places – even if it means venturing deep into politically unfriendly territory.

Onslow County, located along a rural stretch of the state’s south-eastern coastline, is one of those places.

Last month, a few dozen Democrats were gathered there at a local bed-and-breakfast to eat pulled pork and talk party strategy.

“We don’t have to be afraid to be Democrats in rural communities,” Anderson Clayton, North Carolina’s Democratic Party chairwoman, told the small crowd.

“We should be proud of that and wear it on our chest this year when we go to vote.”

As she spoke, she pointed to picnic tables smothered in Democratic paraphernalia: blue tablecloths, blue balloons, and rolls of blue stickers that said “I’m voting with Democrats”. A life-size cutout of Kamala Harris stood nearby.

It was a defiant display in a place like Onslow.

While Trump’s 2020 victory in the state overall was a narrow one, in Onslow County he won by an immense margin of 30%.

“It is really scary to get out and knock doors. I get that,” Clayton said.

While she was speaking, a large truck roared by with a Trump flag waving above its rear.

Her optimism didn’t waver. BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon Drenon

“There is a political realignment happening in rural communities across North Carolina,” Clayton continued, her voice elevating.

“Whether or not people choose to realise it, they’re going to see it.”

The party has made big investments in the state, including signing up 32,000 volunteers, hiring over 340 staff members, and opening up 28 offices, including in rural Republican-led counties like Onslow.

Republicans have begun to notice.

Earlier this month, Senator Thom Tillis told media outlet Semafor “what we’re seeing in North Carolina that we haven’t seen for a time, though, is a really well organised ground game by the Democrats”.

Although Harris has little chance of winning a majority of votes in these deep-red parts of the country, this election will be won on the margins. And so Democrats are betting that a few extra votes in unexpected areas may make the difference in an extremely close race.

Near the end of the campaign event in Onslow County, the energy of the crowd began to fizzle as the sun dipped beyond the trees.

A few lingered, including a 14-year-old who walked up to Clayton to introduce himself.

“After hearing you speak, I decided I’m going to go door knock on Saturday,” Gavin Rohwedder said.

Clayton smiled – one more volunteer today in Onslow than yesterday.

“It’s piece by piece,” she told the BBC. “All people need is somebody to show up.”

But the Democrats’ plans were upended when Hurricane Helene hit in late September.

The storm wreaked havoc in North Carolina, killing at least 95 people. Nearly 100 are still missing.

As residents begin the lengthy process of rebuilding, both parties must also reassess their ground game.

In Buncombe County, where the Democratic stronghold of Asheville is located, some people are still living without internet connection, mobile phone service or clean water, said the county’s party chair, Kathie Kline.

“The typical way to win elections is to knock on doors and to have face-to-face conversations with people,” she told the BBC. “Of course, we had to stop that.”

When North Carolina residents began early voting on Thursday, Kline said some people waited in line at polls to vote, while others queued at government-provided trailers to shower.

It’s a chaotic set of circumstances that Kline agreed could hurt Democrats’ chances in November: “I don’t like saying it out loud, but yes.”

BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonRepublicans are not going to cede North Carolina without a fight.

Strategists say the state looks like a must-win for Donald Trump to take back the presidency. In 2020, it was the only one of the seven battleground states he won.

“It’s very hard for us to win unless we’re able to get North Carolina,” said Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, during a campaign stop last month.

The state’s pivotal role in the election is felt by Republicans on the grassroots level, too.

Adele Walker, who owns an antique store in Selma, North Carolina, is a lifelong Republican, but this is her first year volunteering to canvass.

“This is such an important election,” Walker said, noting her opposition to abortion and fears about illegal immigration.

BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonWhile out canvassing backroads on foot, Walker passed a woman sitting on her porch and stopped to speak to her.

“Hola,” said Walker, who identifies as Hispanic, continuing the conversation in Spanish.

The woman told Walker she was from Honduras and answered “no” when asked if any political groups had previously approached her.

Walker then reached into a cardboard box she’d been carrying under her arm and handed the woman one of roughly a dozen copies of the Constitution translated to Spanish.

She left the encounter in slight astonishment.

“That’s interesting,” Walker said. “Someone said that Democrats were walking through here just last week.

“Guess they missed her.”

BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonAt Mt Lebanon church, Reverend Leach is ensuring everyone understands the urgency of voting.

The church’s origins date back to the mid-1800s, its original congregation composed of African-American slaves. Since then, it has evolved into a hub for social and political activity.

Now, the reverend implored his congregation: “Someone say mission possible.”

Possible, he said, if they – black, rural voters – showed up to the polls.

“Some of you who don’t think your vote matters… We can’t let them take us back 40, 50, 60 years,” Reverend Leach said, echoing a line often used in Harris’s stump speech.

His warning struck a personal chord with William Overton, who was in the crowd. The 85-year-old told the BBC he was voting for Harris and that his number one concern was protecting abortion rights.

“The laws now are worse than they were in the 1950s,” Overton said.

Abortion is an intimate issue for him. His wife had a miscarriage in South Carolina in 1964, he said, and relied on medical care that is now sometimes illegal in that state.

Democrats’ investments into rural areas are felt here, Overton said, adding that he’s been receiving daily campaign calls and texts.

“The excitement is up compared to 2020,” he said.

Michael Sutton, another Democratic voter and member of the church, agreed.

“The way things look even here, in North Carolina, in this small town, everybody is energised,” Sutton said. “It feels like we have a good chance.”

BBC/Brandon Drenon

BBC/Brandon DrenonBut energy is one thing – votes are another.

Standing outside of Mt Lebanon church was 25-year-old Justin Herman.

He told the BBC he voted for Joe Biden in 2020, but feels undecided about this election.

“I don’t know much about Kamala,” Herman said. “Trump, sometimes the stuff he says isn’t ideal. I don’t feel like I can relate to either candidate.”

Then, Herman said something that strikes to the heart of the challenge that Democrats are facing not just in this state, but nationally.

“I don’t know if I’m going to vote at all.”