New Delhi, India – When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was inaugurating a controversial Hindu temple in the northern city of Ayodhya on January 22 this year, J*, a student living hundreds of miles away in the southern state of Kerala was about to post his take on the event on Instagram.

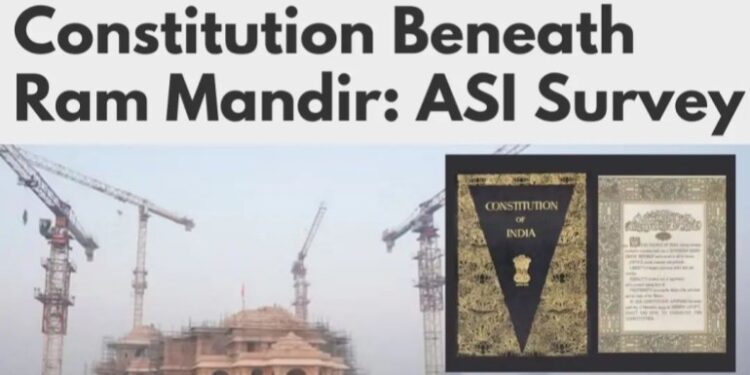

“Remains of Indian Constitution Beneath Ram Mandir: ASI Survey,” the 21-year-old student of humanities posted on his handle, The Savala Vada, criticising the Hindu nationalist leader for allegedly undermining India’s secular constitution by leading a religious ceremony at a temple built on the ruins of a 16th-century mosque.

Since India’s independence in 1947, dozens of Hindu groups, led by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the far-right ideological mentor of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), claimed the Mughal-era Babri Mosque stood at the exact site where Ram, among Hinduism’s most prominent deities, was born. A Hindu mob demolished the mosque in 1992, triggering deadly riots that killed more than 2,000 people and fundamentally altered the course of India’s politics.

After the demolition, the state-run Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) backed the Hindu groups’ claim as the dispute went to the country’s top court, which in 2019 gave the site to a government-backed trust to build a Ram temple. Muslims were given another piece of land in Ayodhya, several kilometres away from the temple, to build a mosque.

A year later, Modi laid the foundation stone for the grand temple and opened it in January this year to kick-start his re-election for a record third term.

As soon as J made the Instagram post, it went viral. It invited backlash from right-wing Hindu trolls. But it also helped The Savala Vada to grow exponentially.

Using humour ‘to report truth’

J and his two teammates working with him on the handle prefer to remain anonymous over fears they “could get attacked or killed”, as they put it.

“There is an entire ecosystem in place that is targeting people who dissent,” J said. “It’s also about protecting oneself when you are speaking in an online space against the ruling establishment and power. Anonymity gives me that protection.”

Al Jazeera sought comments from multiple BJP spokespersons on J’s allegations, but did not receive a response.

Inspired by The Onion, the United States digital media company that publishes satirical articles on local and international news, The Savala Vada was launched by J on July 21, 2023. “Savala” in Malayalam language means onion, and “vada” is a popular South Indian snack. J said his venture is also a “homage” to the kind of work The Onion does.

“The idea came out of a need to create a space where we could discuss and put out contemporary sociopolitical events with a humorous and satirical spin,” he told Al Jazeera.

“It was also about envisioning a democratic, secular and pluralistic space where we report the truth by using tropes of comedy and satire.”

The Instagram handle, said J, started with posts about cultural or historical events but slowly began to focus on news and current affairs to channel what he called his disillusionment with the mainstream Indian media, which many critics have accused of amplifying the BJP’s hate politics against minority Muslims and Christians, as well as being subservient to Modi.

“I belong to a minority religious community and it is extremely difficult to voice your dissent in the current polarised times,” J said, adding that his focus was to “combine humour and resistance” while also reaching out to Gen Z and millennials through his satire.

Apart from The Onion, J said he was also inspired by American comedian George Carlin, British stand-up John Oliver, and Australia’s The Juice Media, which posts satirical takes targeting the government.

Over the past year, The Savala Vada has made more than 680 Instagram posts and gained close to 69,000 followers. Last month, it saw 7.8 million views on its posts and stories.

The handle responds to major national and global events, its precise and direct headlines condensed in a manner that challenges the established narrative through humour and satire.

For example, when Israeli air strikes denied targeting hospitals in Gaza during the continuing genocide, The Savala Vada wrote: “Israeli Defence Forces Claim Gaza Armed With Self-Exploding Hospitals”.

When several Indian journalists flew to Israel to cover the Israel-Palestine conflict, the handle posted: “Air India Flights To Israel Cheaper Than To Manipur for Indian Journos” – a take on the same journalists or their organisations refusing to report on ethnic riots in India’s northeast that have been going on for more than a year.

To mock the state of journalism in India, they once wrote: “Mainstream Indian Journalism Committed To Sacred Duty Of Endangering Lives of Muslims.”

Some of their posts responded to the situation in the disputed territory of Indian-administered Kashmir, which was stripped of its partial autonomy by Modi’s government in 2019. The move, Kashmiris say, is aimed at stealing their resources and changing the demography of the Muslim-majority region.

“Lack of Snow Disappoints Indian Tourists While Lack Of Human Rights Disappoints Kashmiris,” said one of their viral posts about the mountainous region that is popular among Indian tourists for its snow and skiing. “Indian Army Starts Teaching Political Science In Kashmir High Schools,” said another, a reference to one of the world’s most militarised zones where the army enjoys enormous powers and impunity.

Journalist Rana Ayyub, an opinion writer at The Washington Post and a critic of the Indian government, told Al Jazeera she follows The Savala Vada and often shares their posts online to underline the fact that mainstream journalism in India is “gasping for breath”.

“They speak for the oppressed the way our mainstream media don’t,” Rana said. “The handle is an excellent example of holding truth to power by using satire and hitting the nail on the head. They’ve filled the void that the Indian mainstream media left.”

‘Pointing out the absurdity of reality’

But things have not been easy for The Savala Vada. Its X handle has been blocked twice. In the first instance, it changed its handle name and image to “Narendra Modi” to post an Eid Mubarak greeting, and promised to ban the RSS and release all political prisoners to mark the Muslim festival.

The second time the X handle was blocked was when it was mass-reported to the microblogging platform by Hindu right-wing trolls, some with tens of thousands of followers. “It’s a means of intimidation, to stop us from doing our work,” J said. “It clearly means that they are disturbed by what we post.”

J claimed their Instagram handle has also often been shadow-banned by the platform. Then there are online abuses and threats, with people calling them “mullah” (a slur for Muslims), “Jihadi”, “Pakistani”, “Chinese” and “antinational’ among other things.

They have also been threatened with police cases and lawsuits, most of them during the consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, said J.

“It feels scary and depressing. But it is also funny sometimes,” he said. “We receive those slurs and laugh it off. People, mostly from the right wing, often don’t get sarcasm. We pin those comments [on social media] and joke about it.

“Our job is not to offend the sensibilities of any community but to point out the absurdity of the reality we are living in. And satire becomes a powerful tool because it resonates with people,” he said.

Satire is also risky. “To pursue satire in the world’s largest democracy is not easy. A joke or merely having a different opinion can land you in jail,” J said.

India was ranked 159th in this year’s World Press Freedom Index which is released by Reporters Without Borders annually – a marginal improvement from 2023’s 161, but still significantly down from 140 in 2013.

“Free speech in India has sunk into a perilous abyss, and steadily falling press freedom indices underscore the dangers of crossing a line that is becoming increasingly contentious,” watchdog the Free Speech Collective said in a report earlier this year.

The censorship and surveillance of India are the reason, J said, why The Savala Vada does not want to create a website or start a print version, like The Onion. “It will leave a digital footprint online and it will become easy for the government to go against us,” said J.

‘We counter narratives’

During the Indian general elections this year, The Savala Vada collaborated with Australia’s The Juice Media on their Honest Government Ads project, which offers satirical commentary on the state of democracy in poll-bound countries. This year, they included 14 nations, including India, Pakistan, the United States, Indonesia and Iran, among others.

A video posted by the group on YouTube featured a “public service announcement” that critiqued the Modi government for imprisoning opposition leaders, threatening journalists, bulldozing the homes of Muslims and targeting free speech in the world’s largest democracy.

The video was blocked by YouTube following a request by the Indian government. The Juice Media said it received a legal complaint from a government entity in India, which accused the Australian company of provocation to cause riots and insulting the Indian flag and constitution.

After the video was taken down, J feared the government would also act against The Savala Vada. “At that moment, I thought they were going to come after us,” he told Al Jazeera, adding that the fear forced him to remove any reference to The Savala Vada on its Instagram page.

Journalist and media researcher Anand Mangnale said a new pattern of right-wing outrage has emerged on social media, and it is more organised.

“Earlier there would be abuses and trolls online, but what we witness now is much more organised,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Now the groups are being created online to target certain individuals or mass-report any content. It then becomes ammunition for a legal case. The cases are not based on law and order but on the fake outrage they create on social media,” he said.

In recent years, a number of mainstream Indian journalists, who refused to follow the diktats of their employers or quit private corporations, have taken to YouTube and Instagram to continue their work. J said he, like them, is trying to “democratise the same information space with a satirical spin”.

“In the current world that is so bleak and dystopian, we are trying to imagine a different world, a world where we counter narratives, uplift marginalised voices, and fight against hate,” he said.

By making readers laugh.