Black men in England are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage prostate cancer than their white counterparts, while being less likely to receive life-saving treatment, analysis by the National Prostate Cancer Audit has found.

The analysis found that black men were diagnosed with stage three or four prostate cancer at a rate of 440 per 100,000 black men in England, which is 1.5 times higher compared with their white counterparts, who had a diagnosis rate of 295 per 100,000.

Furthermore, the research also found that black men in their 60s who had a later diagnosis were 14% less likely to receive life-saving treatments that have been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for use on the NHS.

The research was conducted by analysing new prostate cancer diagnoses by ethnicity in England from January 2021 to December 2023, using data from the Rapid Cancer Registration dataset and the National Cancer Registration dataset.

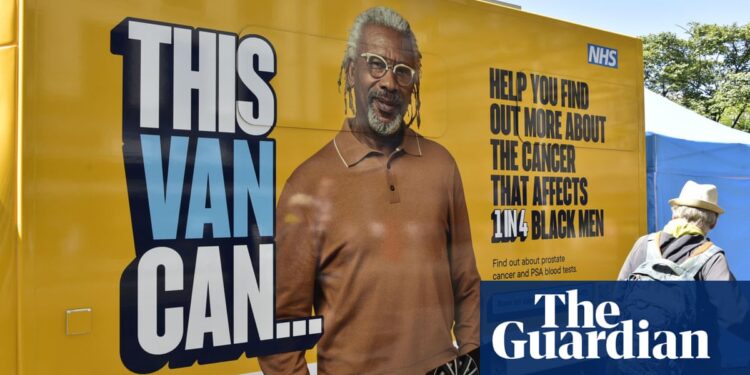

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among British men, with about 52,300 new cases and 12,000 deaths recorded in the UK each year. Black men are twice as likely to be diagnosed and 2.5 times more likely to die from the disease compared with white men.

Prostate Cancer UK is calling for the government’s guidelines to be updated as, under current guidance, it is an individual’s responsibility to find out his risk and decide if he would like to request a blood test.

The charity says that, although black men have double the risk of getting prostate cancer, current government guidelines treat them the same as other men with a lower risk.

Keith Morgan, the associate director of Black Health Equity at Prostate Cancer UK, said that one of the big issues with the NHS is that its current prostate cancer guidelines for GPs are “hugely outdated”.

Morgan said: “Every man has the right to the best care and treatment for prostate cancer. We know that black men are at a higher risk of getting prostate cancer, but this new data from the National Prostate Cancer Audit shows that if you’re black, the odds are currently stacked even higher against you.”

He added: “One big issue is that prostate cancer guidelines for GPs are hugely outdated. In the current guidelines, GPs are told not to start conversations about the pros and cons of PSA testing with men at risk. Instead, it’s up to men to know their risk and start a conversation themselves.

Prof Frank Chinegwundoh, a consultant urologist at Barts Health NHS Trust, said: “It’s about time that we had this data from the NPCA – there’s a desperate need to better understand why black men are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer in the UK and take actions to save lives.

“The disparity that we can see from this data is shocking, and deeply disappointing. This is a consequence of current guidelines; these guidelines treat all men the same, regardless of the fact that some individuals – black men in this instance – have higher-than-average risk of prostate cancer.”

He added: “Some men don’t come forward to their GPs because they think they’ll be invited as part of routine tests – when this simply isn’t true. The sooner the guidelines change, the sooner we can start saving more lives.”

An NHS spokesperson said: “More black men than ever before are having prostate cancer diagnosed at an early stage thanks to awareness campaigns and the work NHS England has been doing in collaboration with Prostate Cancer UK, and we are working with Cancer Alliances to ensure that everyone has equal access to treatment at whatever stage their cancer is diagnosed.

“The UK National Screening Committee makes recommendations on screening and currently does not recommend inviting people without symptoms to have a PSA test because current evidence does not show that the benefits outweigh the harms. But if you have a family history of prostate cancer or have any symptoms you’re worried about, please contact your GP.”

The Department of Health and Social Care have been approached for comment.