Before Bernie Moreno was the 2024 Ohio Republican candidate for Senate, he was the owner of numerous luxury car dealerships, hawking rarified brands like Aston Martin and Mercedes-Benz.

To sell pretty cars, it helps to have pretty dealerships. So in December 2007, Moreno hired the firm Welty Building Company (WBC) “for the design and construction of a Porsche dealership and a Mercedes-Benz dealership” in the Cleveland area, according to a 2014 court document.

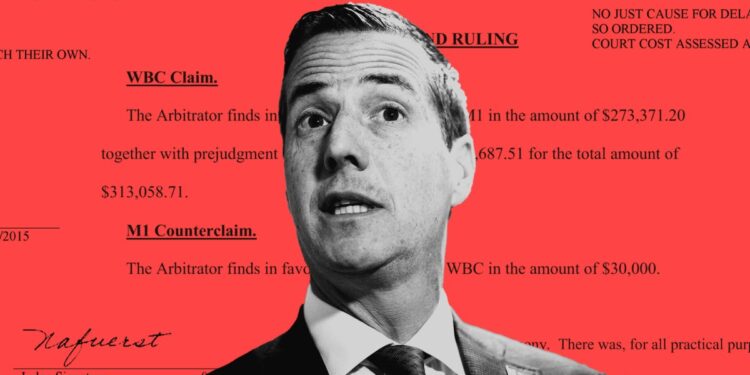

Details of the initial contract, such as exact work orders and total costs, are not public record. But legal documents obtained from Cuyahoga County’s clerk of courts show Moreno’s company M1 Motors failed to promptly pay Welty hundreds of thousands of dollars upon completion of the work. After an arbitrator declared in July 2014 that Moreno’s company owed WBC $313,058, Moreno still didn’t pay, forcing the construction firm to file a legal claim in September 2014 seeking a court to confirm the arbitrator’s decision. As a result, the court scheduled a conference meeting to discuss. Even after that meeting was scheduled, WBC had to file a “Motion to Enforce” before Moreno finally fulfilled his financial obligations to WBC in full, including post-judgment interest, sometime after early January 2015.

Delays aren’t necessarily standard-operating procedure after arbitration rulings. But many people, either out of inability to pay or frustration with the ruling, sometimes drag their feet. Jeremy Fogel, the executive director at the Berkeley Judicial Institute and a former US District Court and state court judge, said he saw similar situations play out all the time when he held the gavel. “It’s a kind of litigation behavior that, unfortunately, is not unheard of,” he says.

This saga, not previously reported, is just the latest example of past legal disputes involving Moreno. A litany of cases from Moreno’s pre-politics days of building a car dealership empire—lawsuits claiming racial, gender, and age discrimination, as well as wage withholding—have clouded Moreno’s attempt to portray himself as a self-made entrepreneur who knows what’s best for Ohio workers because he’s employed thousands of them at his dealerships. This is at least the second example from Moreno’s past in which he did not promptly comply with official legal renderings: Amid proceedings over a case in which he was ultimately found liable for withholding overtime wages from his employees in Massachusetts, Moreno shredded company documents that he and his lawyers “were required to preserve” and “knew or should have known [were] relevant.”

Welty CEO Donzell S. Taylor told Mother Jones that there’s no bad blood between his construction company and Moreno. “Issues like these are not uncommon in the construction business and this one was resolved through the proper channels,” he said in a statement. “We are proud of the work we did for Mr. Moreno and look forward to working with his team again in the future.” But evidently, Moreno was not the CEO’s first pick for the Senate seat: Federal Election Commission records show Taylor donated the election-cycle maximum of $6,600 to one of Moreno’s opponents in the GOP primary, Ohio secretary of state Frank LaRose.

A Moreno campaign spokesperson declined to comment for this story.

For the average Ohioan whose debt is more likely tied to a modest mortgage or credit cards, Moreno’s history of delaying or withholding payment to workers and contractors may impact how they view the candidate whose campaign hinges on his image as a wealthy businessman.

Initially, Moreno’s 2014 legal dispute with WBC took place outside of court. As is increasingly common, WBC and M1 Motors entered arbitration, an alternative legal process that is typically less expensive and tends to be friendlier to large corporations.

The independent arbitrator’s decision explains WBC pursued legal action to seek its remaining balance of $271,371 (which M1 “admittedly owed”), plus prejudgment interest of $39,688. For its part, M1 claimed WBC erred in its design and construction processes to the tune of $1.13 million.

“There was, for all practical purposes, no evidence that WBC’s design was deficient in any respect.”

Moreno’s company alleged construction errors from WBC required M1 to replace portions of the roof and relocate poorly designed drains for more than $100,000, re-do $70,000 worth of decorative concrete and pavers, rebuild a $265,000 car wash, fix exposed metal trusses costing $15,000, and replace a $416,000 Porsche metal wall panel. The arbitrator concluded M1 owed WBC $313,058, minus $30,000 WBC owed M1 for minor construction flaws. The $30,000 credit made the sum M1 owed WBC on July 28 come out to $283,058.

“The testimony of M1’s principal was that he did not believe that WBC’s designer did anything wrong. M1’s expert did not offer any opinion contrary to that testimony,” the arbitrator’s ruling concluded. “There was, for all practical purposes, no evidence that WBC’s design was deficient in any respect.”

According to a motion filed by WBC, Moreno didn’t comply with the decision for more than two months. In Ohio, the deadline to appeal an arbitration decision is 30 days from the date the judgment is rendered in an arbitrator’s report. There’s no evidence Moreno’s company appealed. “Despite the arbitration award itself and numerous requests from Welty’s counsel seeking payment, Ml refused to pay Welty,” a November 7 motion said.

To discuss M1’s non-payment, the court in mid-September scheduled a conference call hearing. Two days prior to that court conference slated for October 15, M1 Motors finally paid WBC its principal debt and pre-judgment interest of $283,058, a full 77 days after the arbitration concluded in July. However, M1 did not pay interest on the principal that accrued between the date of the July arbitration ruling and the date of the belated October 13 payment, which led WBC to file its “Motion to Enforce.”

Finally, a judge settled the matter on January 2, 2015. Citing previous case law, Judge Nancy Fuerst ruled M1 had to pay WBC “post judgment statutory interest.”

“No just cause for delay,” the judge wrote to M1. “So Ordered.”