Major League Baseball legend and National Baseball Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson candidly recalled the racism he faced while playing in Alabama, saying, “I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.”

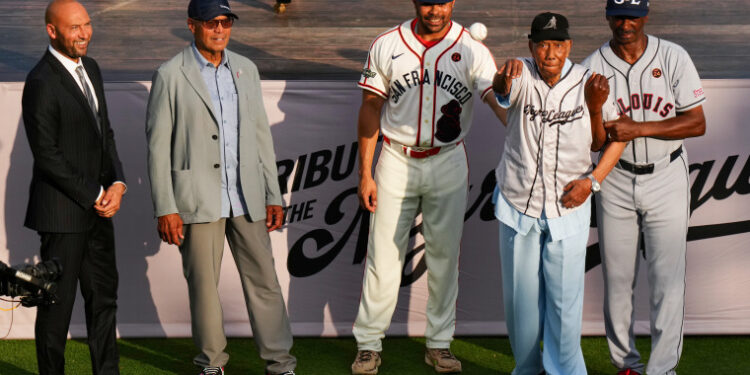

The 78-year-old was among several Black baseball stars at Rickwood Field in Birmingham on Thursday for a Negro League tribute game between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals.

Returning to the field was “not easy,” Jackson said, as he reflected on being called racial slurs and denied entry in restaurants and hotels due to the color of his skin.

“I would never want to do it again. I walked into restaurants and they would point at me and say that n—– can’t eat here,” he explained during a Fox Sports pregame show.

“We went to (Kansas City A’s owner) Charlie Finley’s country club for a welcome home dinner and they pointed me out with the N-word, ‘He can’t come in here.’ Finley marched the whole team out. Finally, they let me in there. He said, ‘We’re going to go to the diner and eat hamburgers. We’ll go where we’re wanted,'” Jackson said.

Thankfully, he had the support of his manager and teammates.

“Fortunately I had a manager, Johnny McNamara. If I couldn’t eat in a place, nobody would eat. We’d get food to travel. If I couldn’t stay in a hotel, they’d drive to the next hotel and find a place where I could stay,” he said. “Had it not been for Rollie Fingers, Johnny McNamara, Dave Duncan, Joe and Sharon Rudi, I slept on their couch three, four nights a week for about a month and a half. Finally, they were threatened that they would burn our apartment complex down unless I got out.”

Jackson started out his career playing for the Birmingham A’s in the minor leagues (the then-Kansas City A’s double-A affiliate) with home games at Rickwood Field in 1967. He went on to have a 21-season MLB career with the Kansas City A’s — which later moved to become the Oakland A’s — and also played with the Baltimore Orioles, New York Yankees and Los Angeles Angels.

But his time in Birmingham was a stark one roiled with racism and the terror of the Ku Klux Klan.

“The year I came here, Bull Connor was the sheriff the year before, and they took Minor League Baseball out of here because in 1963 the Klan murdered four Black girls … at a church here,” Jackson said.

That was the Baptist Street Church bombing in Birmingham where Klan members set off a dynamite bomb in a Black church, killing four girls and injuring more than 20 inside in what the FBI described as a “clear act of racial hatred.”

“I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. At the same time, had it not been for my white friends, had it not been for a white manager, and Rudi, Fingers, and Duncan and Lee Meyers, I would have never made it,” Jackson said.

“I was too physically violent. I was ready to physically fight somebody. I would have got killed here because I would have beat someone’s ass and you would’ve saw me in an oak tree somewhere,” he added.

Thursday marked Major League Baseball’s first game at the field, once the home of the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Leagues. Thursday’s game also honored Hall of Famer Willie Mays, who started his career playing for the Black Barons, who died Tuesday at the age of 93.

The game saw 60 Negro Leagues players honored, in what was the largest official gathering of Negro Leagues players in nearly 30 years, according to the MLB.