For more than a century, Antwerp has been a crucial hub for a $100 billion global industry—one that virtually defines love and commitment, and one that has fueled vicious wars and terrible exploitation. The Belgian city is the world’s biggest trading post for rough diamonds: About 40% of the world’s annual supply of the gems pass through Antwerp’s Diamantkwartier on their circuitous journey from mine to jewelry store.

The diamond district, three narrow streets near the train station, doesn’t exactly reflect the glamor and glitter of the finished product. But the quarter’s modest buildings belie a high-flying business inside. Upstairs in one diamond-trading building on a recent September afternoon, an engineer sat gazing at a golf-ball-sized rock on his desk.

“This is the first time I have seen a diamond this big, and I have worked 17 years in the industry,” said the engineer, Narshi Kalsariya, studying a 3-D image of its intricate facets on his monitor. Dug out of the ground more than 7,000 miles away, in the southern African country of Botswana, the rock weighs more than 1,000 carats, or about seven ounces.

The size alone is notable: Only about 10 gem-quality diamonds that big have ever been found since humans began digging for them more than 2,000 years ago.

But just as notable is the company that currently controls this rare find. It’s not De Beers, the London-based industry powerhouse that mines and trades nearly one-third of the world’s diamonds (most of them from Botswana). Instead it’s a tiny startup called HB Antwerp, which two Belgian-Israeli founders, Rafael Papismedov and Shai de Toledo, launched just four years ago. (A third Belgian-Israeli, Oded Mansori, is a managing partner.)

Papismedov and de Toledo, who met while dropping their kids off at their Belgian school, launched the company with what seemed like a preposterous goal: To upend the 130-year-old business model for diamond trading. The industry has long been an insular one whose skills and opaque trading networks are passed down through generations from fathers to sons, like family secrets.

The two friends wanted to shift control and profits away from hubs like London, Antwerp, and Tel Aviv, to the countries where the diamonds are actually found. They argue that Botswana, with just 2.6 million people and vast diamond reserves (and tourist-attracting elephants) has not gotten its fair share since Western companies began extracting its precious gems nearly 60 years ago.

By many measures, Botswana has benefited hugely. It was one of the world’s poorest countries when diamonds were discovered in the late 1960s, but the World Bank now classifies Botswana as an upper-middle-income country. Yet it still suffers from high unemployment and deep inequality, thanks to its overwhelming dependence on its global trade in diamonds–a natural resource that will someday run dry.

While HB’s model does little to lessen that reliance on a single industry, Botswanan politicians have eyed it as a way to boost job creation and create homegrown manufacturing–and keep more of the profits from the industry in-country. Botswana’s market share in diamonds has surged this year, as the U.S. and Europe began blocking diamonds from Russia, the world’s biggest producer; that growth is giving the model a crucial test run.

These circumstances put HB Antwerp at the heart of a roiling debate over whether Western companies are fleecing resource-rich African countries—including those with critical minerals like cobalt, which are essential for semiconductors—and whether those companies deepen the divide between rich and poor regions. Those issues have come into sharper focus since the COVID pandemic wreaked havoc on supply chains, and as younger consumers increasingly seek products that reflect their social values.

To many critics, diamonds epitomize this controversy. And HB Antwerp’s founders count themselves among the detractors.

“Everything is wrong with this industry,” says Papismedov, sitting in its headquarters atop Antwerp’s old diamond exchange building. For decades, he says, mining companies have hauled out as many rough diamonds as possible, as fast as possible, in order to recoup capital expenses, and then auctioned them in bulk to diamond dealers, who have them polished and cut into jewels.

Vivienne Walt for Fortune

The African countries aren’t the only ones who suffer from this relentless extraction: The diamond market is hurting too. “They are manufacturing things that nobody asked them to manufacture,” Papismedov says. “It is a market for gamblers.” After a post-pandemic spending boom, demand for diamonds has fallen steadily since 2022, as China’s economy has slowed and inflation has risen. De Beers’ revenues sank 21% in the first half of this year, compared with the same period last year, and that downturn came after a steep drop in 2023.

Diamond dealers are now pinning their hopes on Americans splurging this Christmas season. “We’re all hoping the American season will be positive,” Isi Morsel, president of the Antwerp World Diamond Council, the leading trade organization, and CEO of Dali Diamond, tells Fortune. “Prices are the lowest they’ve been since before the pandemic. Nearly half the engagement rings sold in U.S. jewelry stores now are made not with natural diamonds—rocks that are billions of years old, formed hundreds of miles under the Earth—but lab-grown, synthetic diamonds, which cost about one-tenth the price of the real thing.

To attack these problems, Papismedov and de Toledo wanted to flip the industry’s trading model on its head. Rather than paying the Botswana government for parcels of rough diamonds, it offered a cut of the final market price of polished gems, giving the country a far bigger portion of the total revenues.“It’s super simple,” Papismedov says, outlining HB’s pitch to Botswana’s government: “We take 20% off the top. The higher I can sell it, the higher my margin. The other 80% is yours.” Then HB Antwerp tapped Microsoft engineers to build a blockchain infrastructure that could make their plan work, by tracking the provenance of the finished gems—and the revenue they generated—with pinpoint accuracy.

HB Antwerp’s revenues last year were about $181 million and its projected revenues this year are $200 million. That is still minuscule compared with De Beers, which effectively invented the global diamond market—along with the slogan “diamonds are forever,” dreamed up by a De Beers copywriter in the late 1940s. What is more, by sourcing all its diamonds from a single, small Botswana mine that specializes in detecting huge stones, HB Antwerp now possesses some of the biggest diamonds ever found

But HB’s impact far outweighs its balance sheet. The startup has already helped Botswana significantly increase its revenue from diamonds. Already, it has pressured the industry behemoth to alter its own business terms. Now, some fans of HB Antwerp believe its approach could revolutionize other mining industries that have a far greater impact on the global economy.

Taking on diamond giant De Beers

In the diamond-trading hall downstairs from HB’s offices, the mugshots of bad creditors and swindlers are displayed on a peg board. The perpetrators have all been convicted in special diamond courts in Antwerp, and their presence on this board effectively ices them out of the industry.

The mugshot board is a veritable symbol of the community’s insularity–and HB Antwerp’s founders say that they felt a similarly cold shoulder from the old-timers in Antwerp. They saw the startup’s approach as a hare-brained idea, cooked up by outsiders with little understanding of the business. “When we began they laughed at us,” Papismedov says. “They met us in the elevator, and told us we would be bankrupt in two days.”

No one is laughing now. The startup has ignited fierce discussion among diamond producers and dealers, and even complicated De Beers’ decades-long joint venture with Botswana, whose government now glimpses the possibility of more generous profit-sharing. “It’s a small drop in the ocean,” de Toledo says. “But once you understand what is coming out from every stone, you start to doubt everything else.”

Last year, as Botswana negotiated a new contract with De Beers, President Mokgweetsi Masisi insisted on a bigger share of profits, saying, “We must not be enslaved.” (Masisi faced a tough battle for a second five-year term in national elections held on Wednesday; the voting tally was still underway at the time of publication. Opposition politicians say the government has failed to alleviate poverty or Botswana’s 28% unemployment rate—problems that have worsened with the global diamond trade’s slump.)

De Beers, which sources about 73% of its diamonds from Botswana, eventually agreed to double the government’s share of its output (and hence revenues) of rough diamonds over the next decade, to 50% from 25%. De Beers chief people officer Malebogo Mpugwa told Fortune the company was also investing in programs to diversify Botswana’s economy; 80% of the country’s foreign earnings come from its diamond exports. “Even though diamonds are forever, diamond mines are not,” she says.

Neither, perhaps, is De Beers’ clout. Earlier this year, the company was put up for sale by its owner, the London-based mining giant Anglo American. But with no reported offers so far, some analysts express doubts about its future. “Is De Beers’ empire on the rocks?” the specialist newsletter Africa Intelligence asked in late September—a question that would have seemed unthinkable until recently. “HB Antwerp is a real challenge to De Beers’ dominance, undermining it at the most inopportune moment,” the publication wrote. (De Beers strategic communications chief David Johnson dismissed the dire prediction, telling Fortune, “We see a lot of opportunity.”)

The question is, how widely adaptable is HB Antwerp’s model? A Microsoft spokesperson said in an email that the startup is being seen as a blueprint for using Microsoft’s Azure SQL blockchain tech in sectors like financial services and health care. So too could it be a model for trading in commodities like gold or platinum, in which global companies, not the countries of origin, make large profits from the final products.

It is hard to predict when that future will arrive. But Papismedov and de Toledo have already proved a point: A new idea, if brazen enough, can challenge the entrenched practices of even huge multinationals. “The step they took is really small, but nobody ever took it,” says Stuart Krusell, senior director of global programs at MIT’s Sloan School of Business, whose students traveled to Botswana last year to research HB Antwerp’s operations, on a trip partially funded by HB.

Krusell believes industry players like De Beers grew complacent from decades of industry domination—leaving them deeply vulnerable to disruption, especially the boom of lab-grown diamonds, even as inflation and the Ukraine war have shaken the market. He compares De Beers to “General Motors in the late ‘60s,” when the biggest U.S. automaker missed the looming threat from newcomers like Toyota. “You’re a monopoly and you have contracts you thought would never change,” he says. “So why do anything different?”

A ‘family tree’ for every stone

De Toledo grew up watching his father, a diamond cleaver, toil in a closed business with aging traders. He says that when HB Antwerp’s team launched the company in January 2020, their mantra was: “This is a new supply chain. Forget everything that was done until now. Let’s build a new one.”

Their goal was to eliminate almost all the industry’s middlemen, who typically stretch from Africa to Israel, India, and Europe, and to replace them with a stripped-down process, from mine to jewelry store. That includes training local diamond polishers and cutters in Botswana, rather than exporting bulk raw stones to India. HB opened a diamond factory in Botswana last year, with 45 locals trained in Antwerp working in well-paying skilled jobs. The idea is to eventually shift many more operations to the country. “Our only clients are the people where the diamonds are coming from,” de Toledo says.

The supply chain is also vastly simplified since HB Antwerp so far buys all its diamonds from one mine, Karowe, owned by the Vancouver, Canada-based company Lucara—another startup. Under the terms of their deal, HB has first, exclusive rights to all diamonds bigger than 10.8 carats.

The results have stunned the diamond world. No fewer than seven of the 10 biggest diamonds ever found have been discovered in little Karowe—a pinprick on the map—and all but two of those were acquired by HB Antwerp. The huge finds have emerged thanks to a German high-scanning technology called XRT, which Lucara rolled out in Karowe. It detects diamonds deep underground, so they can be hauled to the surface intact—a stark difference from other mines, where mounds of earth are gouged out, then sifted in search of diamonds. And in contrast to the volatile market for small diamonds, giant diamonds are so rare that each can fetch tens of millions of dollars.

In August, Lucara’s Karowe operation found the second-biggest diamond ever unearthed, nearly breaking a record which has stood since 1905 (pieces of that older rock, called the Cullinan Diamond, ended up in the British Crown Jewels); in September, Lucara turned up another giant stone. “These discoveries have sent shock waves through our industry,” says Grant Mobley, a gemologist and editor at the Natural Diamond Council, a trade organization. “It is unbelievable. Nobody expected it.”

But in order for HB Antwerp to pay Botswana 80% of the polished-gem price, diamonds need to be completely traceable, right up through their purchase by the consumer—something that is now possible, thanks to the blockchain. (De Beers has a similar proprietary system, called TRACR, which the company rolled out at scale in 2022, two years after HB’s launch. Company spokesman Johnson says it now tracks about two-thirds of its diamonds.)

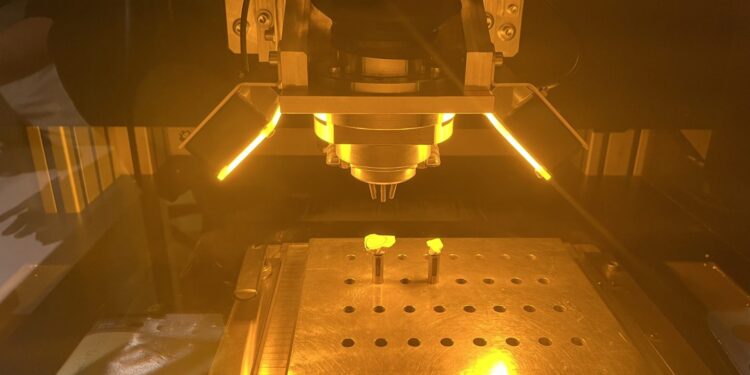

The technology is crucial to every part of HB Antwerp’s work. Up in their offices one day in September, four engineers and data scientists sat at a table tracking on a wall-sized monitor every diamond being worked on by the company, in real time, in both Botswana and Belgium, detailing what each employee was doing. The ledger collects more than 3,000 data points, and is refreshed every 15 minutes, creating what de Toledo calls “an internal audit that constantly looks for loopholes.”

No diamond can be touched without being connected to an “HB capsule,” a small box that sits on every desk in the building. The box tracks each stone’s transfer from one person to another, and connects that transition to the network. As each stone is cut into ever-smaller diamonds, a flow chart displays the origins and connections—a “family tree, with parents and siblings,” as de Toledo calls it.

Beginning next year, HB plans to create “birth certificates” for consumers, allowing them to buy a piece of diamond jewelry with a document showing precisely where and when the gem or gems were found, and how many siblings they have. Experts believe that kind of storytelling is especially important as the demand for diamonds slows. “Consumers care more and more about where a stone comes from,” Mobley says, adding that the tracing process further separates natural diamonds from the lab-made versions, which more and more resemble the real thing. “One is made in Earth billions of years ago, the other is made in a factory in two weeks in India or China,” he says. “When you can tell a story about a diamond’s origin, a person will fall in love with that stone.”

Vivienne Walt for Fortune

HB’s founders hope that is true. Already, they say, their blockchain offers investors rare, reliable information about the potential market for the diamonds, making it easier for the startup to raise capital. “At any given moment, they know what the value is of the stones, and that is associated to that debt,” de Toledo says.

That could determine whether HB is able to replicate its business elsewhere—for example, in nearby Democratic Republic of Congo, home to giant reserves of copper, tantalum and other minerals, and where three-quarters of the world’s cobalt is mined. That country’s president, Felix Tshisekedi, visited HB’s operation in Botswana last year to study its model.

De Toledo sees that interest as a sign that the company might play a bigger role ahead. “The aim of HB is not to be in the diamond industry,” he says. “It is to show the mining world how a supply chain should look.”