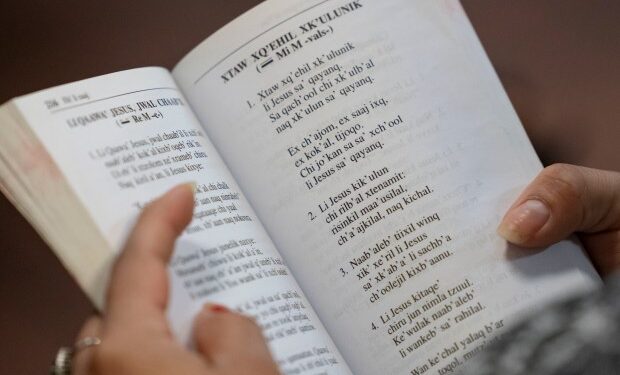

On the Southwest Side of Chicago, a Catholic church service was being held in K’iche’, a Mayan language, and Olga held her daughter, who is 2 years old and 9 months, as they prayed. Both wore a picturesque and handwoven traje, or a traditional outfit from the highlands of Coban, Alta Vera Paz in Central Guatemala.

Her young daughter and her family in Guatemala, she said, are her inspiration to stay resilient amid the newfound turmoil that immigrants, particularly those who are in the U.S. without permanent legal status, face under the administration of President Donald Trump, she said. She finds community at the service every Sunday.

“We come here every Sunday since it started,” Olga said in Spanish after the service.

During the service, the roughly 60 congregants prayed for Pope Francis’ health and for Trump, “so that God can soften his heart towards us,” the minister said in K’iche’. For Olga and countless others like her, the journey to Chicago has not been an easy one.

Indeed, there are now about 30,000 Guatemalans who are living in the Chicago area without permanent legal status, according to data from the Guatemalan General Consulate in Chicago, as unauthorized migration from the Central American country to the United States has risen dramatically over the past decade.

Many of them are coming from a region that is among the poorest and most rural: the Western Highlands, according to the Migration Policy Institute. An estimated 1.3 million Guatemalans were U.S. residents in 2020, up 44% from 2013, with more than half of them living in the United States without legal status, according to its 2022 report.

Many only speak their native language, few know Spanish and most don’t know English.

In Chicago, the resources available to Guatemalans have not kept pace with their population growth. Few organizations offer resources in Indigenous languages. More so, most Indigenous immigrants don’t trust governmental agencies, leading them to hide or live fully under the radar, experts said.

While the resiliency of the Indigenous population in Chicago “is admirable,” said Pablo Pineda, a leader of the Guatemalan community in Chicago and member of the Coalición Coordinadora Guatemalteca del Medio Oeste, “it is also worrisome.”

“Most have learned to live under the radar, never asking for anything, only going to work and home. Few understand what to do in case of getting arrested by ICE,” he said. “They have learned to live only by counting on each other.”

What to know about ICE raids in Chicago — and what your rights are

Now, their struggle goes beyond settling in a foreign land. They face the threat of an even greater fear: the possibility of deportation. Unlike other Central American immigrants, most Guatemalan immigrants do not qualify for Temporary Protected Status or asylum.

But despite the challenges, a vibrant yet often unseen community has begun to flourish even amid the recent, turbulent immigration policies. Their roots in the Chicago area have grown deeper each year, forming a cultural mosaic that blends ancient traditions with the grit and resilience of life in a sprawling city.

After Chicago, Bensenville has the largest population of recently arrived Guatemalans. Though not all, most come from rural Mayan towns in Guatemala, sometimes paying up to $20,000 to cross the southern border.

While migration has become an increasingly common pathway out of poverty, food insecurity, violence, corruption and discrimination, many Guatemalan immigrants in Chicago, in particular Indigenous ones, want to return home one day.

But for now, they are trying to rise above the fear and anxiety by creating community with each other.

Praying for mercy

Before Trump took office, more than 100 people would attend the church service in K’iche’ at a Little Village church. Sometimes, there were so many people that people would have to stand outside, recalled the Rev. Jorge Pec, who arrived in Chicago from an Indigenous town in Guatemala about six years ago.

Soon after news of raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in Chicago spread, only about 30 people would attend the service every Sunday. But their faith in God keeps them strong, he said. For many immigrants, the church service is the only place they can connect to other immigrants. It is their way to cope with the fear and anxiety of ICE agents knocking on their door.

“We must pray for those who intend to harm us and wish them love,” Pec said in K’iche’ during the service. All the while everyone else sang alabanzas like they once did in their hometowns before arriving in Chicago.

Before they found the space in the Catholic church in the Little Village neighborhood to host their service every Sunday, just about a year ago, a group of immigrants began by gathering at one of their apartments, said Antonio, who arrived in Chicago four years ago. He did not provide his last name fearing for his safety.

He said they collected money to buy musical instruments, including an electronic keyboard piano, a guitar, drums and more. Initially, it was just friends and family gathering to sing and practice their faith in their native language at the small apartment, Antonio said. But eventually, the group began to grow slowly.

That’s when Pedro Seb, a missionary from a Mayan town in Guatemala, suggested they rent a place to host the service. But even after collecting money among the group, they figured they wouldn’t be able to afford to pay nearly $4,000 a month to rent a storefront, Seb recalled.

But then Seb met Dolores Castañeda, a community leader in Little Village. She helped to connect the group to the Catholic church in which they host their service now.

“It’s a blessing to have this space, we are sad when we can’t be close to God,” Seb said in Spanish.

Most of those who have recently arrived are young men and women, Pec said. They come with hopes of sending back money to help their families buy land, a home or start a business. Some men migrate alone to send back money to their wives and children. At the church service, a group of young men walked in together. Other young couples and families, like Olga’s, prayed together.

“We pray that we reach our goals here, save money and return safely one day,” Pec added after a recent Sunday service.

In the most recent weeks some immigrants have returned to Guatemala voluntarily, afraid that they would be suddenly arrested, detained and deported without a chance to take their savings home, Pec said.

In Chicago, there are very few resources available in K’iche’ or other Mayan languages, and few have attended Know Your Rights workshops. Still, they’re grateful for the local politicians that have advocated for their rights, he said.

Pineda has lived in the city for 22 years. He said he has witnessed the way the community has grown significantly. His restaurant in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood, Latin Patio, has turned into a hub for the Guatemalan community in Chicago: He hosts fundraisers for those in need and Know Your Rights workshops in Spanish with people that help to translate the information to Mayan languages.

Many don’t know Spanish and some don’t even know how to read because they come from very rural towns where they have no access to education. Most learn Spanish on their way to the United States, he said.

Most of the children born in the United States learn a mix of their parents’ Indigenous language and Spanish.

Guatemalan American children speaking up for their parents

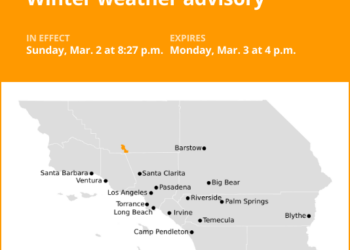

When reports of ICE’s presence in late January spread in a Bensenville apartment complex mostly occupied by Guatemalan immigrants, Rep. Norma Hernández, U.S. Rep. Delia Ramírez and Rosario Ovando, the new ambassador of the Guatemalan Consulate in Chicago, rushed to the area hoping to get information and help families of those who had been detained.

But after hours of knocking on dozens of doors, few opened up, Ramírez said. Even after passing out flyers and letting them know that they were there to help, neither Ramírez nor Ovando have confirmed any arrests made in the premises.

“It is clear that those families are living in fear,” Ramírez said. In the few instances that people opened the door, it was children who would come out. “It was my opportunity for those little kids to see me and know that if the daughter of a woman who crossed that border is now on the other side protecting them, those little kids should know that I want them to have the same opportunity that I had,” she said.

Ramírez, who grew up in Chicago, said that the community in Bensenville is the fastest-growing Guatemalan community in the state. But she acknowledged the challenges they face and the limited resources available in the area.

“They come from extremely impoverished areas in Guatemala. I’ve been to those regions,” she said. They face language and health issues because some only speak their Indigenous language, she added.

When school buses arrived to drop off children from school that afternoon in January, only a few parents walked to pick up their children and rushed back inside their home. Heidi Giron, 15, went to pick up her siblings instead of her mother, who was still avoiding going outside. The teenager had stayed home from school to stay with her parents, afraid that if she came home, her parents wouldn’t be there anymore.

“We don’t know how many people they took, but we saw ICE here,” said Giron, as she showed a video of the agents on her phone.

As soon as they saw the agents walking outside their apartment in the morning, the family turned off all the lights, locked the doors and went to hide in one of the rooms, she said.

After a few hours, the adults sent Giron, who was born in the U.S., to check if the ICE agents had left the premises.

“I fear that some of the kids here are getting home now and their parents aren’t there,” Giron said.

Her mother, Alejandra García, said she had been staying home from work because of the continuous reports of raids and ICE presence in the area.

“But I don’t know how long we can continue doing that,” García said.

As school buses continued to arrive so did Heidi Rivas, a teacher at a local school. They followed the buses to the apartment complex to make sure the children arrived safely and with their parents after hearing of the rumors earlier that day, Rivas said.

“We heard about everything that went down this morning so we were making sure that our students got home OK,” Rivas said. They were also passing out red cards, which have information in Spanish about what to do in case they’re encountered by ICE agents.

“Hi, Ms. Rivas,” a young boy yelled from afar.

“Did you get home OK?” she yelled back. “Yes!” he said.

“Salúdame a tu mamá. Say hi to your mom,” she responded as she hugged Giron. Other people only looked out their windows, still afraid to go outside.

Mistrust

The mistrust the community has in local leaders and politicians is rooted in the way they were treated in Guatemala, Ramírez said

Pineda said: “Some are not even willing to attend workshops.”

The Guatemalan Consulate in Chicago mostly shares resources on its social media sites and invites people to visit pages that offer information in their different languages. Ovando said she hopes to expand the services offered at the consulate to provide legal help.

She said her office has not received an exact number of how many Guatemalan nationals have been arrested or deported over the last month since Trump took office.

“The consulate is here for you with the services that we can provide, with our allies in jails, with our mainland who is already forming a plan to make a safe return and to have the tools to assist in the sense that we can guide them to find a job to return to their communities to insert themselves back to society there,” Ovando said.

Ovando acknowledged that the community in the area has vastly grown and there are limitations. Yet, she said that it is important for everyone to have their documents in order to safely return and encourage Guatemalan immigrants with U.S.-born children to apply for Guatemalan citizenship.