It seemed poetically fitting that my trip to Auschwitz would take me through Vienna, the starting point of my great-grandparents’ journey. Robert and Paula Stricker’s path was significantly more circuitous than mine: they were shuffled from Vienna to Dachau to Theresienstadt, and finally Auschwitz, where they were murdered along with approximately 1,100,000 other souls.

My voyage to Krakow began with the same spirit and, perhaps, the same words as my great-grandparents’ death-march did – “grüß Gott,” said the Austrian Airlines gate agent, which translates roughly as, “May God greet you!” I suppose it is only a matter of time before we all have our own chance to greet God. Some of us may get to do so under peaceful circumstances. Others, like my relatives, inside the fiery furnaces of an ungodly regime.

For reasons I still don’t fully understand, I have decided to undertake this pilgrimage to Auschwitz on January 20. Perhaps it is to pay my respects. Or maybe it is to give myself some perverse reassurance that no matter how bleak the current state of humanity appears, it could be much worse.

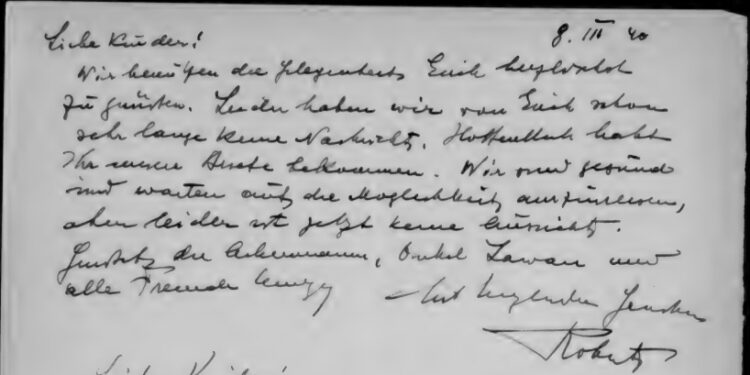

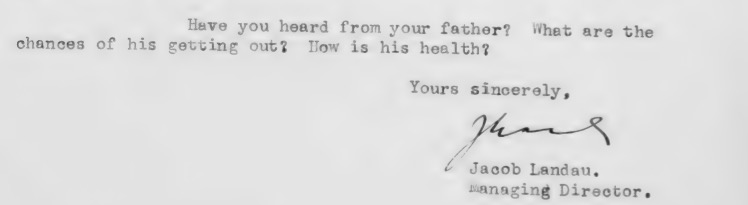

My in-flight reading material comes in the form of a 1,051-page .pdf I have downloaded from the Center for Jewish History, clinically entitled, “Stricker, Robert, 1879-1944.” Over the years, I have reviewed it many times, and by the time I’m at 30,000 feet, I am once more taking the well-worn journey through the macabre digital flipbook documenting the tribulations of my great-grandparents. It begins with tender, reassuring correspondence from the early 1940s, always beginning with “Liebe Kinder!” – “Dear Children!”…

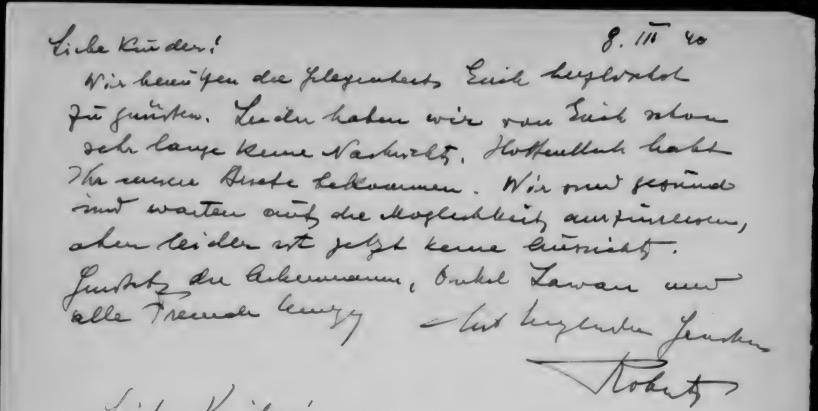

From there, it grows progressively more ominous, with the mail envelopes bearing stamps denoting that they were pre-opened by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, the Nazis’ Armed Forces High Command.

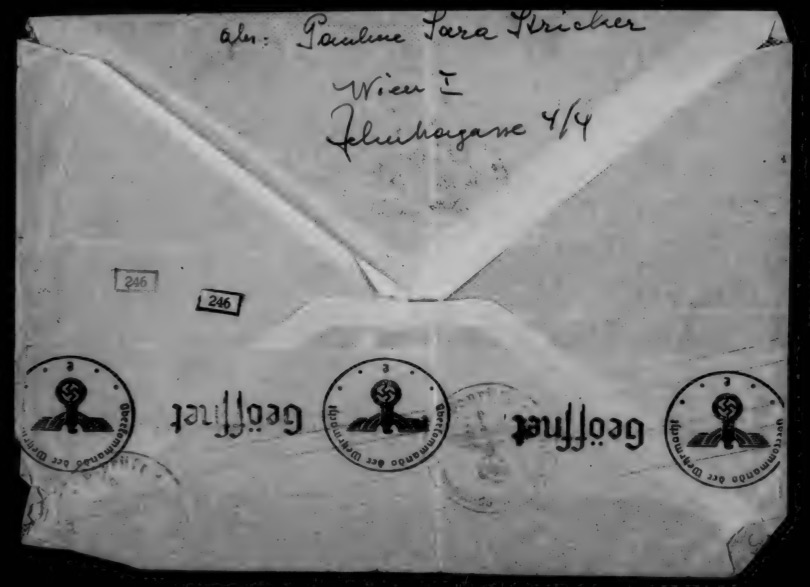

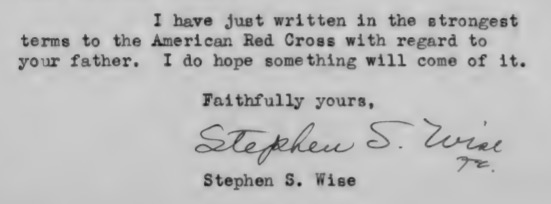

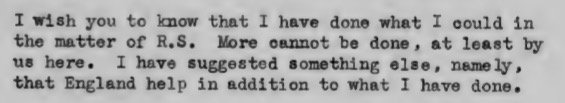

Before long, the flipbook goes from inquisitiveness…

To alarm…

To despair…

Before abruptly transitioning to mourning.

After that, the remainder of the flipbook turns to justice, in the form of my grandfather’s role at the Nuremberg Trials where he spent months looking into the eyes of his family’s murderers.

That Bavarian city was selected as the location of the trials in an attempt to create a roundtrip for The Nuremberg Laws—the hateful, antisemitic, and racist legislation born there in 1935. My grandfather and the rest of the Allies hoped it would be a fitting place for the execution of the Nazi ideology, along with 13 of the 24 defendants who received the death penalty. Some, like Hermann Göring, who ordered the development of the “Final Solution” against Jews, used a potassium cyanide capsule the night before he was to be hanged to implement the final solution on himself.

I have made it through almost all of the dossier by the time I land in Krakow. Back home, the United States is getting ready for the inauguration of the 47th President, who used a 2019 speech to the Israeli American Council to Jewsplain to attendees: “A lot of you are in the real estate business because I know you very well. You’re brutal killers. Not nice people at all. But you have to vote for me; you have no choice.” I try to avert my eyes from the TV news monitors throughout the airport.

Six months prior, I had to abandon plans to visit in the springtime. Afterwards, Cameron, my friend since elementary school, reassured me, “The time to go to Auschwitz would be in the dead of winter.” As soon as I exit the airport, I realize that Cameron was right. It is a little after 6 p.m. and almost pitch black, with a thick, damp fog and a persistent wind that makes the 22°F temperature feel significantly colder. I am bundled from head to toe and yet feel the bite of the frosty conditions. Millions of Jews, along with Roma and Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Freemasons, Afro-Germans, the disabled, homosexuals, POWs, ethnic Poles and other Slavs, religious dissidents and political opponents—all of them were subjected to this weather. Dressed in nothing more than flimsy striped pajamas.

The taxi from Krakow to my hotel in Oświęcim takes less than an hour, and after a hearty dinner of assorted pierogi, I sleep in a warm, soft bed. If Elie Wiesel were looking down on me, he would agree that I am, as he described in Night, “far from the crucible of death, from the center of hell.”

Describing Auschwitz in words is an attempt to put language to the ineffable. I obey the English humorist Douglas Adams who said, “Let us prepare to grapple with the ineffable itself, and see if we may not eff it after all.” But before I eff it with a few details that are difficult to fully fathom unless you are physically present at Auschwitz, I must underscore the significance of the hallowed testimonies that remain required reading. There’s Wiesel’s Night. Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Or Primo Levi, Charlotte Delbo, Eddy de Wind, Tadeusz Borowski, Ruth Klüger, or or or or.

Standing on the vast grounds of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp defies comprehension. At nearly 350 acres in size, it’s about three Vatican Cities. Or two Forbidden Cities. Or two Disneylands. I guess twice The Happiest Place on Earth equals one Arbeit macht frei. In all, the 10 miles of barbed wire encircled 300 barracks and other buildings that held, at its peak, about 125,000 human beings. That’s roughly the population of Hartford, Connecticut. Or Topeka, Kansas. Or the attendance at the Burning Man festival—actually, two Burning Mans.

What struck me about the civil engineering marvel that is Auschwitz is that it was born of the need to not just commit mass murder, but hide the evidence. The Nazis didn’t try to conceal the prison camps, but they went to tremendous lengths to deny that they were actually death camps. Had they wanted to flaunt their genocidal practices, they could have built a mountain of carcasses or filled valleys with corpses. But while mass graves existed, they were quite the exception.

In physics, there exists a conundrum known by the sweet and almost quaint name “the three-body problem.” Before it became better known as the title of Liu Cixin’ sci-fi novel and subsequent Netflix adaptation, it was understood as the challenge of predicting the motion of three objects interacting with each other through a force, such as gravity. While two bodies interacting can have rather predictable outcomes, once three bodies (or more) are at play, foreseeing the effects becomes virtually impossible. At Auschwitz, murdering a person was something of a two-body problem. Covering it up became a million-body problem.

The need to erase the evidence of 1,100,000 bodies put into motion one of the most diabolical Rube Goldberg machines in the history of humankind. Its architect was Karl Bischoff, who designed Auschwitz by working backwards from his estimate of the maximum incineration capacity at the crematoria:

Bischoff’s figure of 4,756 bodies in a 24-hour period included down time for cleaning and maintenance, and concluded that a total 5 crematoria were needed to meet those targets. Those limits meant that only so many people could enter the gas chambers at a given time. And that in turn meant that the vast majority of Auschwitz’s prisoners would have to be placed in a holding pattern. But unlike airplanes that can simply circle until they have been cleared for landing, Auschwitz’s prisoners needed to be stored somewhere, necessitating the construction of miles upon miles of barracks. Auschwitz’s constant backlog of mortals renders it, in many ways, a monument of human arrears.

The Nazis were exceptionally thorough in their coverup. While the SS took many pictures of Auschwitz, their photography did not include the gas chambers or crematoria. When they communicated about their murderous acts, they employed euphemisms, most notably Sonderbehandlung (“special treatment”), more commonly used in its abbreviated form, S.B.. They went to great lengths to dispose of the tons of human remains in nearby rivers, fields, and marshes. And in the final days of Auschwitz, the SS detonated crematoria and gas chambers as they retreated.

One exception to their thoroughness came in what was for me one of the most unexpected places. Inside a display on the second floor of Block 4 is an exhibit of the hair shorn from prisoners upon arrival at the camps—and on departure. Two tons of it. It is impossible to describe the living testament of those braids, locks, payots, and ponytails, each existing in suspended animation of a life not lived. If the Nazis were so fastidious about hiding their tracks, why keep all the hair?

Business.

As with so many of Auschwitz’s side-hustles, the hair was harvested and sold. It was repurposed in Nazi uniforms, military-issue socks, and stuffing for mattresses so the living could sleep comfortably at night. German companies bought bales for twenty pfennig per kilogram.

The victims’ remains were even weaponized–literally. Dr. Miklos Nyiszli was allowed to live by working as an assistant to the infamous “Angel of Death,” Dr. Josef Mengele. In Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account, he described the cruel upcycling in which these locks gained a lethal second life:

Hair was also a precious material, due to the fact that it expands and contracts uniformly, no matter what the humidity of the air. Human hair was often used in delayed action bombs, where its particular qualities made it highly useful for detonating purposes. So they shaved the dead.

Zyklon B, the poisonous gas used in the gas chambers, was yet another of the infernal Rube Goldberg inventions born of the Million-Body Problem. The constraints placed on the Nazis’ killing apparatus included not exposing their own soldiers to too much bloodshed (too traumatizing), and not using bullets (too expensive). The solution to the Million-Body Problem had to entail maximum lethality for minimum cost.

Hydrogen cyanide was developed in California in the 1880s, where it was used to fumigate citrus orchards. It existed essentially as Zyklon A. After some tinkering, the Nazis packaged it in sealed canisters bonded to adsorbents, such as diatomaceous earth. These Zyklon B pellets were then dropped through small openings in the roof of the otherwise sealed gas chambers. The pellets then vaporized, so long as the temperature was 81°F or higher. The Nazis economized and pre-heated the gas chambers as little as necessary, relying on the innocents’ body temperatures to ensure that the Zyklon B activated. More than a million people were murdered in Auschwitz using their own 98.6° body heat.

Until I came to Auschwitz, I believed that its gas chambers were, like at Dachau, filled with fake shower heads, out of which the gas poured like exhaust from an automobile tailpipe. One grisly similarity to an actual shower room was that prisoners were ordered to disrobe and told to remember the numbered hooks where they left their clothing so they could retrieve them “afterwards.”

I stand before this monument of mutilated dreams, and I cannot help but think, eight decades after the liberation of Auschwitz, how much has humankind actually changed?

I had also believed that victims perished almost instantaneously. But it usually took more than 20 minutes for people to die a painful death of asphyxiation. And of the hundreds crammed into the gas chamber, there would inevitably be some who did not die from the Zyklon B gas. Those provisional survivors were then singled out and shot.

As I look into the crumbled remains of the gas chambers where my great-grandfather and great-grandmother perished, I shudder at their final moments of terror, pain, and suffering. Near the end of his life, Elie Wiesel wrote in Open Heart, “I have already been the beneficiary of so many miracles, which I know I owe to my ancestors. All I have achieved has been and continues to be dedicated to their murdered dreams—and hopes.”

The Auschwitz-Birkenau camp is divided near its center by the “death road”–the path down which my great-grandparents likely walked immediately upon their arrival due to their age, joined by children and babies for the same reason. At the end of that road is the International Monument to the Victims of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Camp, which features plaques translated into 23 languages. They read:

For ever let this place be

A cry of despair

And a warning to humanity

Reading these words prompts the umpteenth stream of tears down my cheeks, this time because of the grace and mercy at the epicenter of such mercilessness. These are also tears of gratitude for our predecessors, who sent a warning etched in steel about the danger of leaving unrestrained our darkest, basest tendencies.

I have tears of gratitude for Poland, which has embraced IMBYism to harbor this former hell on Earth. It has allowed the name of its town, Oświęcim, to be eclipsed by “Auschwitz,” the German title assigned by the vanquished invaders.

At the same time, these tears are tears of profound disappointment. I think of the self-help saying, “Most people overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years.” I stand before this monument of mutilated dreams, and I cannot help but think, eight decades after the liberation of Auschwitz, how much has humankind actually changed? The wealthiest man in the world has just greeted inaugural supporters by shooting his arm diagonally upward, palm facing down. Twice. He has taken to the social media platform he owns to provide reassurance to his 200 million followers with a series of Nazi-themed puns. Meanwhile, just over 500 miles from Auschwitz, Ukrainians fight a tyrannical invader, while back in the United States, the leader of the free world is signing a slew of executive orders as part of his “dictator on day one” presidency.

Here we are, fellow homo sapiens.

As I exit the camp’s gates—a privilege not afforded to my great-grandparents or more than a million others—a group of teenagers from a Warsaw high school are concluding their tour with me. Their next stop is 20 minutes away at Energylandia, an amusement park containing 19 roller coasters. Perhaps a few rides on the Frutti Loop Coaster is what a teen needs as a proper salve for a severe day. I would not have been capable of metabolizing this place at 14. I am still not able to today.

Gabriel Stricker, a member of Mother Jones’ board of directors, was previously the Chief Communications Officer of Twitter and is currently an advisor to the Cancer Research Institute.