After racking up a number of award nominations and wins, the film Sing Sing is being re-released in theaters. It also makes history as the first movie to simultaneously be available to nearly 1 million incarcerated people across the country.

It will screen inside correctional facilities in California, New York, Texas and 43 other states, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

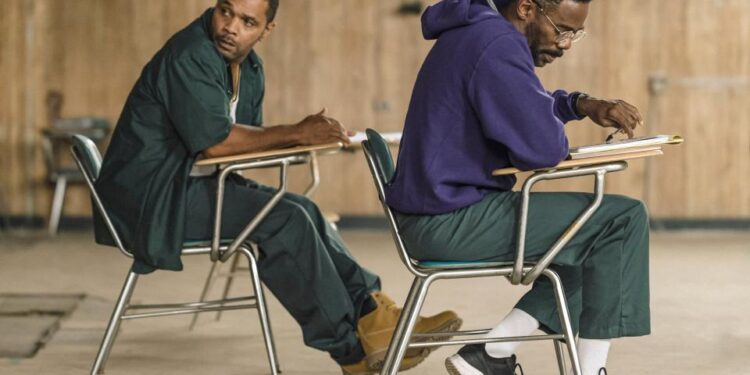

The film is based on the real-life Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program that has been in operation since 1996 at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison roughly 30 miles north of New York City.

Charles Moore, RTA’s director of programs and operations and an alumnus of the program at Sing Sing, told Yahoo Entertainment that he’s “thrilled to have the RTA story of hope, resilience and transformation on the big screen for individuals to see nationwide.”

He said the partnership with distributor A24, nonprofit learning platform Edovo and RTA is “especially poignant for me as a person who spent nearly two decades in prison.”

“This collaboration will be an opportunity for those incarcerated to connect and build on the film’s emotional resonance and to begin contemplating a similar journey for themselves,” he added.

In Sing Sing, Colman Domingo plays John “Divine G” Whitfield, a real person who was a star actor and playwright in the RTA program while wrongfully incarcerated for many years. A majority of the actors who portray his fellow RTA members are also alums, including Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, who plays a version of himself when he first joined the program and began building a friendship with Divine G.

“I’d probably still be in and out of prison, never would’ve changed my life, had it not been for this brother and his tenacity about getting me into the program,” Maclin told CBS Sunday Morning in November.

RTA uses theater, dance and music, among other art-related workshops to help reduce recidivism, i.e., the tendency to relapse into criminal behavior. According to the organization, less than 3% of incarcerated participants go back to prison, compared to the nationwide average of 60%.

Maclin has been open about how his involvement in the program changed his life.

“We had to create mechanisms to soften the crash after the plays were over because it felt like escaping prison for a few days,” he told Variety in November. “Those programs weren’t just art — they were survival.”

Edovo founder and CEO Brian Hill told the Hollywood Reporter that “storytelling has an incredible way of sparking hope and building connections, even in the toughest circumstances.”

“With Sing Sing, we’re giving incarcerated individuals an opportunity to see themselves in a story of resilience and transformation, and to feel inspired to imagine new possibilities for their own lives,” he said.

The film shows flashes of the reality of prison that is so often depicted in pop culture — violence is commonplace, freedom is limited and humanity is questioned. But that’s not the focus of the film.

“We don’t ever deny the barbarism, atrocities and violence that can go on in prison, but what we wanted to show is that that’s not the only thing that goes on in prison,” Maclin said at an August screening.

At Sing Sing’s Brooklyn, N.Y., premiere in July, co-star and RTA alum Sean Dino Johnson said he wanted viewers to “remember the resilience of the human spirit, the power of humanity.”

In the movie, his character says the program gives incarcerated individuals the opportunity to “become human again.” Now that message is available to the people still in prison — not just those on the outside looking in.