Attorneys in the corruption trial of ex-House Speaker Michael Madigan came to court Thursday expecting a drag-out fight about the implications of a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision on the federal bribery statute, including a dispute over how jurors should define the word “corruptly.”

But toward the end of the five-hour jury instruction conference, U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey told lawyers for both sides that as far as he could tell, the high court’s decision had limited bearing on Madigan’s case.

In fact, the justices in Snyder v. U.S. — a bombshell case involving the the former mayor of Portage, Ind. — offered no actual guidance on how to define “corruptly,” Blakey said, leaving attorneys beholden to long-established precedent established by the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“The Snyder case is not controlling on the issue at all,” Blakey said. “It does not interpret, much less reinterpret, the term ‘corruptly’ … That doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant, but the fact of the matter is that the 7th Circuit authority remains intact in its definition of ‘corruptly.’”

Madigan’s attorneys had argued that the Snyder decision recast what the word “corruptly” means in the federal bribery statute known as 666, asking the judge to define it for the jury in Madigan’s case as “acting with knowledge that the person’s conduct is unlawful.”

Madigan lawyer Lari Dierks said such a definition would help jurors delineate between a citizen’s right to petition government officials and a criminal scheme to influence a public official.

“The question is, when does that influence cross the line into an illegal bribe?” Dierks said. “What (the word) ‘corruptly’ does is draw that line to make sure that innocent conduct doesn’t get swept in.”

But Blakey cited two 7th Circuit opinions from the past decade that he said offered the clearest guidance. The first says an agent “acts corruptly when he understands that the payment given is a bribe, reward, or gratuity,” though the judge said the term ‘gratuity’ would have to be removed because of the Snyder ruling.

The second case says corruption entails “the payee’s knowledge that the payor expects to achieve a forbidden influence or deliver a forbidden reward,” Blakey said, quoting directly from the opinion.

Blakey also said that from his understanding of the law, prosecutors have to prove a defendant knew he was partaking in a bribe — but they don’t have to prove the defendant knew the bribe was illegal.

“The government must prove a corrupt factual awareness that the exchange was a bribe, not a subjective legal awareness that such exchange is prohibited by law,” Blakey said, acknowledging that the difference is “nuanced.”

That means Madigan’s defense team likely will not be allowed to use what’s known in legal parlance as a “mistake-of-law” defense, arguing that the former speaker simply didn’t know his actions were illegal.

Blakey said that if Congress meant to include an ignorance-of-the-law defense in the 666 statute, it would have used the traditional term “willfully” instead of the more nebulous “corruptly.”

And, the judge noted, all the lawyers said in court in November that they had no basis to make a mistake-of-law argument.

“I don’t see the view of any of the parties in this case that a mistake-of-law defense is available, and I don’t see how I can rewrite the statute and add in some otherwise ‘prohibited’ or ‘wrongful’ (language) that doesn’t have any kind of definition to it,” the judge said.

Blakey added that the circuit’s pattern instructions that they’re working off of “are the same instructions that have convicted multiple governors and other people under 666 for a generation, and none of them have a mistake-of-law (defense).”

The judge held off making any final rulings on the issue, giving the attorneys a chance to confer among themselves and make alternate proposals.

“Everything I just said is not an opinion, it’s a thought process,” he said. “…Why don’t you guys look at that, and then I’m happy to talk more about it.”

The trial, which began Oct. 8, is expected to head to closing arguments later this month.

Though jury instruction conferences are typically tedious, this one has taken on added importance in Madigan’s case after the Snyder ruling in June raised the bar for what prosecutors have to prove.

In its decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “gratuities” — or gifts given as a thank-you for actions a public official has already taken — are not criminalized under the federal statute and that prosecutors must prove there was an agreement ahead of time.

A jury appeared to be struggling over that very issue before deadlocking in September in the trial of former AT&T Illinois boss Paul La Schiazza, who was accused of bribing Madigan in an alleged scheme that also is part of Madigan’s case.

Last month La Schiazza’s attorneys lost a bid to throw out the charges, and the case is now set for retrial in June.

Blakey, meanwhile, declined to dismiss any of the bribery counts against Madigan, saying the indictment clears the hurdle set in the Snyder case by alleging Madigan performed official acts in exchange for various things of value, including ComEd jobs for his associates.

Still, the high court’s ruling is likely to significantly influence the language the Madigan jury receives in the legal instructions, which will lay out what prosecutors need to prove on the five counts in the indictment that relate to the 666 statute.

Despite the lack of guidance on the term “corruptly,” some of the proposed jury instructions are clearly influenced directly by the Snyder case, including the inclusion of the word “exchange” when defining what is an illegal bribe.

“If the bribe is to be paid after an official action occurs, then the government must prove that the bribery agreement existed before the official action was to take place,” the proposed instructions read.

Blakey had hoped that by the time the trial wrapped, the 7th Circuit would have new pattern jury instructions that would deal with the Snyder ruling. But last month the judge told the parties the new pattern instructions would not be ready in time.

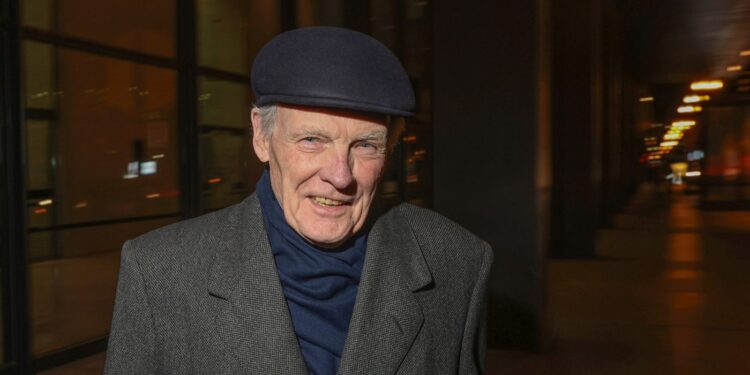

Madigan, 82, a Southwest Side Democrat, and his longtime confidant, Michael McClain, 77, of downstate Quincy, are charged in a 23-count indictment alleging Madigan’s vaunted state and political operations were run like a criminal enterprise to amass and increase his power and enrich himself and his associates.

In addition to pressuring developers to hire the speaker’s law firm, the indictment accuses Madigan and McClain of conspiring to have utility giants Commonwealth Edison and AT&T Illinois put the speaker’s associates on contracts requiring little or no work in exchange for Madigan’s assistance on key legislation in Springfield.

ComEd allegedly also heaped legal work onto a Madigan ally, granted his request to put a political associate on the state-regulated utility’s board and distributed bundles of summer internships to college students living in his Southwest Side legislative district, according to the charges.

Both Madigan and McClain have denied wrongdoing.

After an extended holiday break, jurors are expected to return Monday to hear from more witnesses in Madigan’s defense.