This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

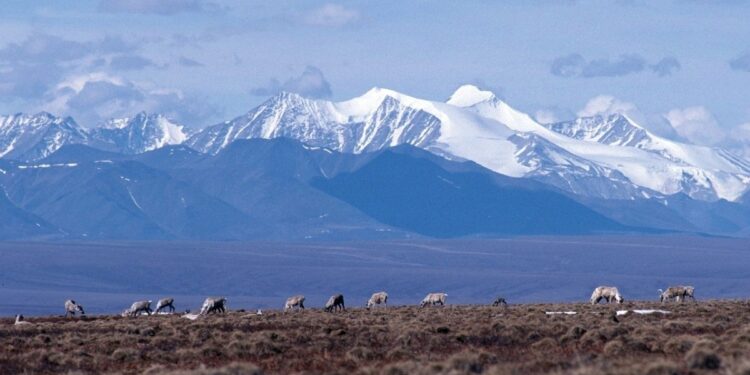

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is one of the Earth’s last intact ecosystems. Vast and little-known, this 19 million-acre expanse along Alaska’s north slope is home to some of the region’s last remaining polar bears, as well as musk oxen, wolvesm and wolverines. Millions of birds from around the world migrate to or through the region each year, and it serves as the calving grounds for the porcupine caribou.

Donald Trump has called the refuge the US’s “biggest oil farm.”

The first Trump administration opened 1.5 million acres of the refuge’s coastal plain to the oil and gas industry, and under Trump’s watch, the US government held its first-ever oil and gas lease sale there.

“It is about a federal government that thinks it knows better than the people who have lived on and cared for these lands since time immemorial.”

In a few weeks, when Trump takes office again, the refuge–one of the last truly wild places in the world–is awaiting an uncertain future.

The president-elect has promised to revive his crusade to “drill baby drill” on the refuge as soon as he returns to the White House in January, falsely claiming it holds more oil than Saudi Arabia. Project 2025, the conservative Heritage Foundation’s blueprint for Trump’s second term, calls for an immediate expansion of oil and gas drilling in Alaska, including in the ANWR, noting that the state “is a special case and deserves immediate action.”

From his end, Joe Biden is moving to limit drilling in the region as much as his administration can. Experts are debating how much oil and gas there is to gain if Trump were to open up the region for drilling again. But Alaska’s Republican governor and Native Alaskan leaders in the region say they are eager to find out—seeing the potential for a major new source of revenue in the geographically remote region.

Other Native leaders and activists have banded with environmental groups that oppose drilling on the refuge and are gearing up for an arduous battle.

“I see it as a David and Goliath fight,” said Tonya Garnett, a spokesperson for the Gwich’in steering committee, representing Gwich’in Nation villages in the US and Canada. “But we are resilient, and we are strong, and we’re going to keep fighting.”

Garnett, who grew up in Arctic Village, just south of the refuge’s border, has spent most of her life trying to protect the refuge. Trump’s election has upped the urgency.

The Gwich’in call the refuge’s coastal plain Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit—the “sacred place where life begins.” It serves as the breeding grounds for a 218,000-strong herd of porcupine caribou, which the Gwich’in have hunted for sustenance through their entire history. “We don’t even go up there, because we don’t want to disturb them,” said Garnett. “We believe that even our footprints will disturb them.”

Environmental concerns go beyond the caribou. Scientists have warned that mitigating the risks drilling will pose to polar bears will be impossible. A 2020 study in PloS One found that the infrared technology mounted on airplanes used to scope for dens are unreliable.

Experts have also warned that the trucks and equipment used in even the initial stages of exploration could cause severe damage to the remote tundra, endangering the habitat of the bears and many other sensitive species. With the climate warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet, bears are already struggling to hunt on a landscape that is quickly melting away below them. “Drilling puts the polar bears straight in harm’s way,” said Pat Lavin, the Alaska policy adviser for the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife.

All the while, extracting and burning more fossil fuels is guaranteed to accelerate global heating–further degrading the region that is home to not only bears and other wildlife, but also several Alaskan communities.

Melting permafrost is releasing mercury, as well as greenhouse gases, and eroding infrastructure as the literal ground beneath many Alaskans feet begins to disintegrate. “It’s a scary thing,” said Garnett.

The political zeal to drill in the Arctic has remained strong, despite industry skepticism over how much there would be to gain from drilling the ANWR. The US Geological Survey estimates that between 4.3 billion and 11.8 billion barrels of oil lie underneath the refuge’s coastal plain, but it remains profoundly unclear how large the deposits are and how difficult it will be to get to them. Its location in the remote, northernmost reaches of the continent, bereft of roads and infrastructure, makes it exceptionally difficult and expensive to even explore for petroleum.

“We think there is almost no rationale for Arctic exploration,” Goldman Sachs commodity expert Michele Della Vigna told CNBC in 2017. “Immensely complex, expensive projects like the Arctic we think can move too high on the cost curve to be economically doable.”

And yet, Republicans seem determined. Environmentalists have wondered if this zeal is more political than practical. “To some extent, this issue has become symbolic,” said Kristin Miller, executive director of the Alaska Wilderness League. “There’s an idea that if they can drill the Arctic Refuge, they can drill anywhere.”

The Biden administration is working to limit exploration as much as it can in its remaining weeks in office. After two of the companies who’d bought leases in the first Trump years relinquished them voluntarily, in 2023 the Biden administration cancelled the remaining leases. However, the administration is obligated to hold a final oil and gas lease sale in the refuge as required by Trump-era law. Biden’s team has indicated it will be offering up just 400,000 acres–the minimum required by the 2017 law, with contingencies to avoid habitat for polar pears and the caribou calving grounds.

It’s unclear who would bid for these leases. Already, several big banks have vowed not to finance energy development there, and big oil and gas companies have avoided the region—in large part because drilling into this iconic landscape remains deeply unpopular with many Americans.

During the first Trump term, only two small private companies submitted bids for leases on the refuge, and later relinquished them. The other main bidder was the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA), a public corporation of the state of Alaska, which is suing the Biden administration over the cancellation of its leases last year.

That group has already approved $20 million to potentially bid again on leases for oil exploration in the region, even amid growing scrutiny of the extraction-focused group’s use of taxpayer funds, and its failure to meet its mandate of encouraging economic growth.

The group did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment on how it plans to proceed.

Garnett said she sees the unending drive to drill into this land as a form of colonization. The Gwich’in have built their livelihoods and culture around the porcupine caribou, and by disrupting the caribou’s habitat, oil industrialists will destroy the Gwich’in’s history and way of life, she said.

“We’re ready to fight, to educate, and to go with a good heart,” she said. “Because that’s what we have to do.” The Gwich’in tribes have urged the Biden administration to establish an Indigenous sacred sight on the coastal plain in the coming weeks.

Not all Native groups in the region agree on that plan. Iñupiaq leaders on the North Slope have said the petition infringes on their traditional homelands, and threatens oil and gas development that could benefit the Iñupiaq village of Kaktovik, the only community located within the refuge boundaries.

In an October op-ed, Josiah Patkotak, mayor of the North Slope borough, which includes Kaktovik, said that the territory in question “has never been” Gwich’in territory.”

“This is not about the protection of sacred sites” he wrote in response to news that the administration would consider designating the site. “It is about a federal government that thinks it knows better than the people who have lived on and cared for these lands since time immemorial.”

Nathan Gordon Jr., the mayor of Kaktovik, said he’s excited about the incoming administration, and its openness to renewing oil and gas exploration. “We would be able to provide more for the community, more safety regulations and infrastructure,” he said.

Gordon said he disagrees with the argument that oil and gas exploration would decimate the caribou, noting that residents in Kaktovik, too, rely on the herd for sustenance hunting. “We wouldn’t do anything to hurt our own herd,” he said. “I don’t see the main negative effects that everybody else sees.”

One thing he has in common with tribal members on the other side of this issue, is that he too has spent years advocating on the issue. “I’ve been working on this ever since I’ve been a tribal councilmember,” he said. “We want to be able to use our lands.”