Daniel Espinoza first saw his future wife from across the room at a dim Las Vegas casino. It was New Year’s Eve 2014, and a beautiful woman with big brown eyes and dirty-blond hair was playing slots. Espinoza, a construction worker and party boy who was about to turn 30, sat down next to her. Julia was bubbly and confident, and, Espinoza soon found out, made her living as an escort.

Their relationship quickly went from “zero to a hundred,” says Espinoza. A month after they met, she had effectively moved into his Las Vegas apartment. A couple of days later, she brought home two Chihuahuas: Skinny Mini for her and Fatty for him. Soon after, the couple traveled to the Mexican village where Espinoza grew up, and he introduced Julia, a white 33-year-old from New York, to his mother. Then, surrounded by a small group of friends and family, they got married in a civil ceremony.

Espinoza never saw himself as the settling-down type, but when Julia told him that year that she was pregnant, he literally jumped with joy. “It was the best feeling of my life,” he says. Each night, he’d listen to Julia’s belly and assure his son-to-be that his father would protect him.

But Espinoza knew his son would face his share of challenges. Julia, whose last name has been omitted to protect her privacy, had a long history of using heroin. A few weeks after their son was born, in late 2015, Julia was incarcerated for nearly two years for a parole violation, leaving Espinoza with the infant. (Child Protective Services, which got involved after the child’s birth, had deemed Espinoza a safe caregiver.) Sometimes, Espinoza hired a babysitter; sometimes, he brought his son with him to construction sites. He called his son “my little engine,” because, he says, “he kept me going forward.”

In 2018, after Julia had returned, their second child, a girl, was born. A year later, Julia found out she was pregnant again, and the family moved into a bigger home. Espinoza was buoyed by the news of each pregnancy. “A kid, for me, is another reason to live,” he says.

The couple’s relationship was difficult to categorize: They were married, they loved each other, and they co-parented, but by the third pregnancy, their dynamic had become strained. Espinoza was frustrated by Julia’s continued drug use and didn’t want her friends around, because some of them used, too. She began spending more and more time away from home, saying she needed space.

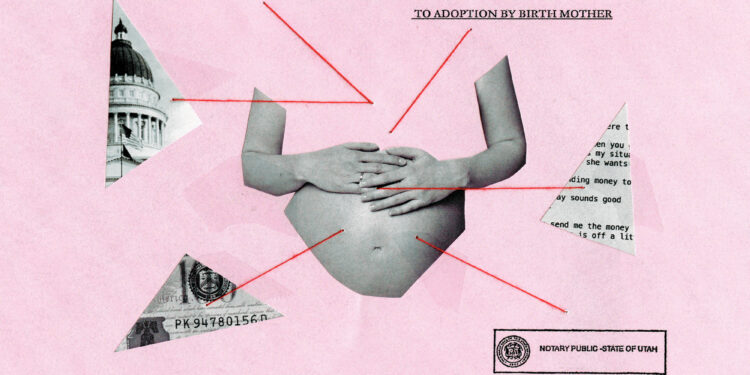

What Espinoza didn’t know was that Julia had learned about a new way to make money to support her addiction: putting their baby up for adoption. On Google, she found an agency in Utah, Brighter Adoptions, that would provide an apartment, medical care, and a weekly allowance during her pregnancy. Once she had the baby and signed the adoption papers, she would receive even more cash. Not that she really thought she would relinquish her baby, she told me recently. “I was on heroin at the time,” she said, “and so at first, it started out like kind of a hustle for me.”

Eight weeks before her due date, she hitched a ride with a friend to Layton Meadows, a sprawling apartment complex just north of Salt Lake City. It’s one of the many places where Utah’s cottage industry of adoption agencies houses expecting mothers, who are enticed by free lodging and cash stipends.

Depending on whom you ask, the state’s laws are the most “adoption-friendly”—or the most exploitative—in the country. Many states allow mothers to change their minds days or even weeks after consenting to adoption, but in Utah, no such safeguard exists: Once the papers are signed, the decision is irreversible. While married fathers must be notified of adoption proceedings, the children of unwed fathers can be placed for adoption without notification or consent. Like other states, Utah prohibits adoptive parents from paying pregnant women to give up their children, but there’s no cap for how much they can pay for services related to the pregnancy, as long as the expenses are “reasonable.” And Utah is the only state where finalized adoptions can’t be dismissed even if the adoption was fraudulent.

“It’s shark-infested waters to procure moms, to then procure their children, to then broker the baby to an adoptive parent.”

Wesley Hutchins, an attorney in Salt Lake City who has helped facilitate more than 1,400 adoptions, is blunt in his critique of the state’s laws: “You can lie, you can misrepresent, you can do pretty much everything you want.”

Adoption has long been embraced across the political spectrum as a sort of panacea: a solution to unplanned pregnancies, an answer to infertility, a benevolent way to grow families. In the two years since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision—in which Justice Amy Coney Barrett noted that adoption helps avoid the “consequences of parenting and the obligations of motherhood”—lawmakers in conservative states that have enacted abortion bans have doubled down on promoting and incentivizing adoption, with glossy promotional campaigns, tax credits for adoptive parents, and changes to high school sex-ed curricula to promote adoption. In May 2024, Senate Republicans introduced the More Opportunities for Moms to Succeed (MOMS) Act, which would establish Pregnancy.gov as a clearinghouse of pregnancy and parenting resources that would show adoption agencies, but not abortion clinics.

Yet experts worry that the enthusiasm for adoption is fueling an industry that has long been analogized to the Wild West—one in which scattershot, state-by-state regulatory oversight and the desperation of birth and adoptive parents alike create conditions for predatory adoption operators to flourish. Birth mothers typically come from poverty and often lack stable housing and other support systems. Adoptive parents, who, according to some estimates, outnumber available infants 45 to 1, routinely pay upward of $80,000 to adopt.

“It’s shark-infested waters to procure moms, to then procure their children, to then broker the baby to an adoptive parent,” says Kelsey Vander Vliet Ranyard, the policy director at Ethical Family Building, a nonprofit that advocates adoption reform. “People are competing for women.”

Utah may be the most extreme version of what it looks like to champion adoption with little oversight, but when it comes to reproductive justice, the extremes have a way of becoming the new normal. Hutchins says adoption lawyers frequently discuss making states more adoption-friendly. He lists the typical questions: “Where’s the easiest place for adoptions to be performed? Where’s the easiest place to get around the rights of biological parents?” The answer? “Time and time again, that comes up as being Utah.”

Sandi Quick, the owner of Brighter Adoptions, was waiting at the apartment complex when Julia arrived. Quick facilitated about 50 adoptions a year, in addition to taking care of more than a dozen children of her own, but in the days to follow, she made Julia feel like her only focus. Quick texted to make sure Julia had woken up for various appointments, provided rides to her new doctor, and even gave her quarters for laundry. This attention was key to Quick’s philosophy. Birth mothers “are some of my favorite people,” she wrote on the agency’s website. “There is no greater act of love than to put that tiny one’s needs above your own desires.”

Julia was chatty over text, writing about what she was up to (perusing adoptive parent profiles, walking to Dollar General), how cute her kids are (Im not just saying that cause they are mine, she wrote), and what Espinoza thought of her drug use (Hes a lil judgemental on that cause im their mom and i am too). As for Quick, Julia wrote, You truely must be an angel.

On the intake paperwork, Julia did not disclose that she was married to Espinoza, instead checking the box for “single.” She was, however, upfront about her drug use, noting that she’d last used meth “a few months ago” and last injected heroin “days ago.” (The adoption paperwork, as well as the text exchanges, were later introduced as court records.)

Quick assumed Julia was using while in Utah, but this wasn’t particularly out of the norm. As one Layton Meadows resident told me, so many of Brighter Adoption’s clients there are on drugs that they’ve come up with a nickname for themselves, a combination of “Sandi” and “Xanax”: “Xandi’s girls.” Quick later said in a deposition, “These girls that need our help are the ones that are going to have a record a mile long, and that will not stop us from helping them.”

Three days after Julia arrived in Utah, she flew to Las Vegas. She said she planned to pick up her car and drive back that night. The next morning, when Quick hadn’t heard from her, she sent a series of texts asking where Julia was and when she was coming back. Over the coming days, Julia was in sporadic touch, offering excuses for why she was lingering in Las Vegas: Her daughter had been in the emergency room; she needed an oil change; she was in jail for a few days over outstanding warrants.

Finally, Julia said she was ready to head back, but she’d used some of her weekly stipend to pay for bail. She asked Quick to send gas money. It would be the first of many exchanges in which Julia wanted cash and Quick wanted her to return to Utah.

At first, Quick was skeptical. I could wire you the money to money gram but I’m extremely nervous that you won’t come back again. But by that afternoon, Quick had relented, sending Julia the money—only for Julia to go dark again. Quick sent a string of texts asking where she was, pleading, please come back!!!

“Get on the road right now and make it to Utah,” Quick texted Julia. “I will moneygram.“

Eventually, after almost two weeks away, Julia returned to Layton Meadows, where she spoke with two sets of prospective adoptive parents over the phone, weeping in between. There were only two couples, Quick acknowledged, because “there are no more open to the IV heroin.” (Drug use during pregnancy can cause health complications for the developing fetus, including withdrawal symptoms after birth.)

Julia liked the second couple, Mary and Perry. Perry was a pilot who had recently started a church congregation in their small Alabama town. (At the couple’s request, Mother Jones is not using their last name.) They were ecstatic about adopting and seemed kind, sending Julia flowers and asking how much contact she wanted to have with them before she gave birth.

It was around the time Julia spoke with the couple that she started feeling stuck. What had begun as a way to get some easy money was turning into a real plan to place her child for adoption. If she backed out, Mary would be heartbroken, but if she went ahead, she risked devastating Espinoza. “It was a bad situation,” Julia told me. “I was just hustling for money, but I don’t have a hateful heart.”

Then again, she thought, perhaps adoption wasn’t the worst idea. She was addicted and overwhelmed by the prospect of more kids. In mid-November, Julia texted Quick from Las Vegas to say she’d started having slight contractions. Get on the road right now and make it to Utah, Quick replied. I will moneygram.

Arrangements like this one, in which a pregnant woman coming from Nevada and a couple in Alabama plan for a potential adoption in Utah, are possible due to a constellation of individuals and organizations across the country that enable, and often profit from, adoptions.

“Facilitators,” the organizations that find pregnant women considering adoption, frequently target poor women living in places with restrictive abortion laws. A Birthmother’s Choice, a facilitator that Brighter Adoptions has worked with, offers not only free housing and financial help to pregnant women, but also fun weekly outings and amenities like pools and transportation to shopping centers.

Targeted Google ads are key to finding women. A Birthmother’s Choice pays for ads to come up in response to Google searches like “adoption agencies near me,” “i’m pregnant now what,” “how do i stop pregnancy,” and, strikingly, “planned parenthood of tennessee” and “planned parenthood in pa.”

Ranyard, who tracks the adoption industry’s trends, says that since Dobbs, facilitators and agencies have been more aggressive about targeting pregnant women with financial incentives. Ads for A Birthmother’s Choice, for example, read “Get Paid for Adoption.”

“Consultants,” meanwhile, find aspiring adoptive parents. For years, Brighter Adoptions has worked with Faithful Adoption Consultants, a Georgia-based organization that, as of 2018, required prospective adoptive parents to pay a $4,000 fee and get a signoff from a pastor stating the couple is active in a pro-life church. A form for prospective parents includes questions like “Please tell us your understanding of the gospel and briefly describe your salvation experience,” and “In what ways do you represent Christ in your home?” Over the past 15 years, the organization has helped place more than 2,000 babies.

Recent keywords that Brighter Adoptions paid for include “pregnant homeless need help,” “places for pregnant women to live,” and “do birth mothers get paid for adoption.”

In the middle are adoption agencies, which sell themselves as supporting pregnant women in crisis while finding loving homes for their children. They, too, use aggressive Google ad targeting. For many, the top expense—more than legal fees or support services for women—is marketing to pregnant women considering adoption.

Recent keywords that Brighter Adoptions paid for include “pregnant homeless need help,” “places for pregnant women to live,” and “do birth mothers get paid for adoption.” If one searches “giving baby up for adoption,” ads for Brighter pop up in 30 states.

In an email, Quick said her work reflects a need for a stronger social safety net, including better access to health care, child care, services to combat the opioid crisis, and support for victims of domestic violence. “Without such changes, however, many women are forced into heartbreaking decisions about their futures, their bodies, and the children they bring into the world,” she wrote. “I am someone who ends up filling these gaps where our social safety nets fall short…The work I do isn’t easy, but it is essential.” (Quick didn’t comment on Espinoza and Julia’s case out of a desire to protect “the privacy and safety of the mother.”)

But agencies requiring women to travel to Utah or other “adoption-friendly” states put their clients in compromising positions, says Ashley Mitchell, who runs Knee to Knee, a support program for birth mothers. Isolated from their communities, women can become dependent on an agency that keeps track of the details of their lives. Mothers working with Brighter sign forms allowing the agency to communicate directly with their health care providers, including accessing information discussed in counseling sessions that may be relevant to the adoption. The paperwork adds that adoption is a “highly confidential and protected service,” but “if you chose to air grievances on social media about Brighter Adoptions you are waiving your right to privacy.”

“There is a very thin line between the ethical practice of adoption and a reproductive trafficking situation,” Mitchell says. “I think it’s very easy to cross that line.”

In 2018, Tia Goins, a new mother in Detroit in the midst of a housing crisis and postpartum depression, Googled adoption options. As The Cut recently chronicled, she got a phone call from Flossie Green, a facilitator who works with A Birthmother’s Choice, and within 24 hours was on a plane from Detroit to Utah to place her 3-month-old for adoption with Brighter Adoptions. Goins immediately had second thoughts, telling Quick on her second day in Utah that she wanted to call off the adoption. But, she says, Quick said she was busy.

The following morning, Shaylee Budora—Quick’s daughter and a counselor with the agency—showed up at Goins’ hotel room with a notary public and relinquishment papers. “I’m in a whole other state with a whole newborn, around these people that I really didn’t know from a can of paint telling me they’re gonna help me,” Goins told me. “What do I do? I don’t have any way back home. I don’t have any money to get back home. So what do I do?”

She signed the papers, the adoptive couple appeared in the room, and, in tears, Goins handed them her child. “It happened so fast,” Goins says. Only then did Quick coordinate her flight home. On the way to the airport, she gave Goins $4,000 in cash.

According to the paperwork that Brighter Adoptions uses today, mothers who place their children for adoption are provided financial support through an eight-week post-delivery recovery period. Mothers also sign a form acknowledging that they know that adoption is completely voluntary. In an email to Mother Jones, Budora wrote, “If a client shows any hesitation or doubt, the process is halted and only resumed if the client clearly indicates their desire to proceed and can articulate confidence in their decision.”

Ever since that day in 2018, Goins has spent countless hours calling cops, lawyers, and state regulators in hopes of reuniting with her daughter, to no avail. She’s also reviewed the fine print of the paperwork she signed at the hotel. It notes that if a mother who’s arrived in Utah changes her mind, Brighter Adoptions will provide travel home in the form of a Greyhound bus ticket.

From a young age, Quick knew she wanted a big family. She wrote about babies in her journal, prayed for babies, dreamt of babies. “I have always wanted to be a mom to the masses,” she later wrote on her personal blog, Habitat4Insanity. By the time she was 27, in 1998, she had eight children, four of whom were adopted.

A year later, Quick opened her own adoption agency called A TLC Adoption. It was devoted “to placing children of color,” according to its website. Some agencies at the time charged less for Black babies, but Quick, who was white and Mormon, found this practice abhorrent. (Quick says she has since left the church.) She refused to change her rate—a minimum of $12,000 per adoption—based on race. “I wanted to spend my time doing what I love and earning money in the process so I could continue living the life I wanted to live…Above the poverty line that is,” she wrote on her blog.

It was a good time to get into the adoption industry in Utah. In the mid-’90s, state policymakers, concerned about what they said was an epidemic of children born out of wedlock, passed legislation stipulating that unwed fathers didn’t need to be notified of adoption proceedings. The act of having sex was reason enough for him to “be on notice that a pregnancy and an adoption proceeding regarding that child may occur,” according to the legislation. State law also stipulated that fraud wasn’t grounds for the dismissal of an adoption.

What may have started as religiously motivated, pro-adoption state policies have since boosted an industry that now pulls in adoptive and birth parents from all over the country.

During legislative deliberations, Rep. Mary Carlson, a Democrat representing Salt Lake City, worried aloud that under the new law, birth fathers who were lied to wouldn’t have legal recourse. “We have basically undermined the ability of a father to have a part of the child’s life,” she said.

Among those lobbying for the legislation were attorneys from Kirton McConkie, the law firm representing the Mormon Church. Over the years, the firm has used its considerable sway to push adoption-friendly laws. In the Mormon faith, a couple is married for eternity and their children are sealed to them in an eternal family. For some Mormons, the motivation to adopt comes from a desire to place children into those eternal family units, says Hutchins, the adoption attorney. He describes himself as a pro-adoption Mormon, but he notes that in some cases, church members use the faith to justify adoption practices that are unethical or illegal. “They feel like the ends justify the means,” he says. “They’re getting children out of one-parent, problematic homes into stable, two-parent homes.”

What may have started as religiously motivated, pro-adoption state policies have since boosted an industry that now pulls in adoptive and birth parents from all over the country.

Quick’s agency hit the ground running, placing 306 babies in almost seven years. She also grew her own family with the help of TLC. When the agency couldn’t find a placement for a baby boy in 2002, “I hopped my ass on a plane to pick up my new son,” she wrote. The same thing happened with a baby girl four months later and then again the following year. By 2005, she had 13 children.

Quick shut down TLC the following year, amid a crumbling marriage and financial troubles. By 2011, she was working for an agency called Heart and Soul Adoptions, run by her good friend Denise Garza. The two women had a lot in common: Garza was also an adoptive parent of several children who had helped facilitate hundreds of adoptions.

Quick worked at Heart and Soul for six years before peeling off to start Brighter Adoptions in 2017. A year later, state regulators shut down Heart and Soul for 22 violations, including defrauding adoptive parents, falsifying documents, and paying pregnant women amounts of money that “very well may incentivize their decision to relinquish,” according to a judge’s order. (Quick was only briefly mentioned in the order, in reference to submitting a receipt without referencing what it was for.) Garza’s license was revoked for five years.

Contrary to the state’s orders, Garza kept working in adoption, referring pregnant women to Brighter and giving the women rides. When state regulators caught wind of Garza’s involvement in 2019, Brighter Adoptions was demoted to a conditional license for five months and ordered to stop associating with Garza.

But Brighter kept working with Garza. In 2022, Garza applied for personal bankruptcy on two separate occasions. She was entering her fourth year of being shut out of the adoption industry and was deep in debt, with eight children living at home and a potential foreclosure on a $1.4 million house. Buried in the bankruptcy filings, though, Garza noted that she was still making some money: specifically, $13,700 per month as a “consultant” for Brighter Adoptions. Quick had continued to give work to her old friend after all.

Garza says she takes responsibility for mistakes at Heart and Soul but noted that the claim that birth mothers are coerced into giving up their children “is unequivocally false.” She disputes the accounts of her involvement with Brighter Adoptions, saying she was not involved with the agency in 2019 or 2022. Asked to explain why the bankruptcy filings suggested otherwise, she didn’t respond.

“You kind of turn a blind eye to some degree,” said one adoptive mother. “It’s like you’re…baiting them in.”

State regulators don’t seem to have noticed the public filings. In 2023, the state restored Garza’s license, to the surprise and dismay of Utah adoption reformers, and she started another agency. Garza told the Salt Lake Tribune that she embarked on the new venture to help expecting mothers in the aftermath of the Dobbs decision.

Efforts to clean up adoption in Utah have faced staunch industry pushback. In 2011, Hutchins started hearing stories about unwed fathers unwittingly losing custody of their children. As the president of a trade group called the Utah Adoption Council, he wanted to champion ethical practices. To understand what was going on, he had his then-wife call several Utah agencies, posing as the sister of an out-of-state pregnant woman interested in adoption. In recorded calls, agency representatives walked her through how she could keep the birth father from finding out about the adoption. One rep urged her to tell the birth father the baby died. Another told her that when the pregnant woman arrived in Utah, they’d give her an envelope with thousands of dollars in cash for her to spend as she wanted. When Hutchins circulated transcripts among the trade group, he redacted the names of the agencies, some of whose leaders were in the room. “The response I got was, ‘How could you do this, Wes?’” Hutchins recalls. “And my response to that was, ‘How could I not?’” He resigned from his presidency the following year over concerns about the treatment of birth fathers.

In 2019, Democratic state Sen. Luz Escamilla introduced legislation to crack down on advertising by facilitators. Seeing ads about available babies on social media, she says, was “as if you were on Amazon, shopping for a dress or a piece of furniture.” But even this small regulatory step proved to be one of the most difficult bills for Escamilla to pass in her 16 years in the legislature. One adoption lawyer became so heated that Escamilla had to call security. “They’re like, ‘You’re trying to stop kids from being adopted,’” she remembers. “I’m like, ‘No, I’m trying to make sure no one is profiting off of children.’”

Adoptive parents, meanwhile, are left with mixed feelings about supporting problematic practices to adopt children they love. “I am so thankful for adoption, because we wouldn’t have the family we have now if it weren’t for adoption,” one woman who adopted through Garza’s Heart and Soul told me. But, she said, “in all honesty, it still doesn’t feel like it makes it right, you know?” After adopting in Utah, the woman adopted in Florida, another state with lax regulations. She said the attorney she worked with in Florida routinely gave birth mothers gift cards worth thousands of dollars, knowing that many of the women sold them for drugs.

“You’re at such a desperate point where you want a family, and you want to provide that baby that needs a family a good, loving home, and you know you can. So…you kind of turn a blind eye to some degree,” said the adoptive mother. Of the birth mothers, she said, “It’s like you’re…baiting them in.”

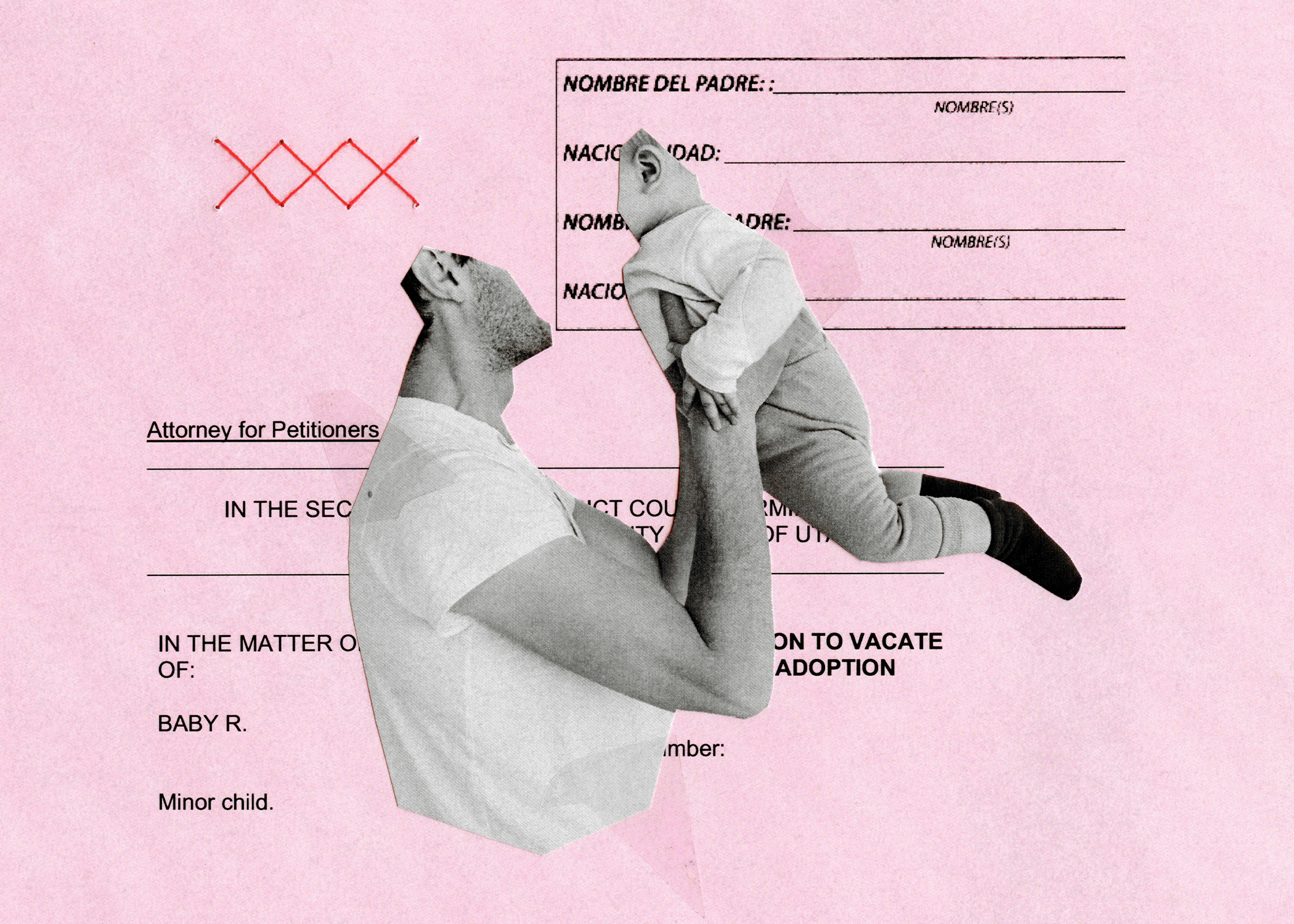

On a chilly morning in November 2019, Julia gave birth to a boy at the Jordan Valley Medical Center just south of Salt Lake City. Two days later, Budora and a notary public visited her at the hospital to go through the adoption forms. Julia initialed them to confirm that she wasn’t under the influence of drugs, that she hadn’t received payment to induce her to place her child for adoption, and that she wasn’t married to anyone during the pregnancy. In two separate forms, she noted that Espinoza was the father, giving his full name, date of birth, and location of conception. She checked boxes indicating that she had not told Espinoza that she had traveled to Utah and that she had never experienced domestic violence with Espinoza. She initialed to indicate her understanding that, once she signed the adoption consent form, her decision was irrevocable. At 10:15 a.m., Julia signed away her rights to her son.

After she signed, Julia says Quick gave her about $7,000 in cash.

“Being on drugs and not really wanting to have another kid at the time—that’s why I just went ahead and did it,” Julia says. “But I didn’t know that Utah law was like that. I thought that [Espinoza] was going to be able to say he wanted the kid and they were gonna give it to him.”

Back in Las Vegas, Espinoza was increasingly alarmed. He had no idea where Julia was, let alone if she’d given birth. “I tried to call her; she never answered,” he says. He went through her files and was surprised to find a sonogram from West Jordan, Utah. “I’m like, are you kidding me?” He looked up her search history and saw she’d been Googling adoption. He called agencies to ask if they knew Julia’s whereabouts. “Nobody would give me information,” he says.

“He says I sold my baby.”

It wasn’t until the day after Christmas, five weeks after Julia gave birth, that she told Espinoza that she had placed their son for adoption. Espinoza found out about the adoption and wants to kill me literally, Julia texted Quick. Espinoza hadn’t been violent with her before, but now he was livid, texting her things like, If i dont get my kid today i swear on my kids u r dead julia. (Espinoza told me he didn’t mean this literally.)

Don’t give him any information, Quick wrote back.

Soon after, Espinoza called Quick directly, telling her that he was the father. She told him he needed to hire an attorney and bring the matter to court. Espinoza didn’t have money for a lawyer and tried to navigate Utah’s court system on his own. In January 2020, he filed a motion to stay the adoption, but he filed it incorrectly. He obtained a copy of his marriage certificate from Mexico; Julia had ripped up the couple’s copy long ago after a fight. In April, Julia and Espinoza together filed an affidavit to amend the baby’s birth certificate, saying the change was necessary because, they wrote, “Father wasn’t added at birth.”

Finally, that May, Espinoza found a lawyer he could afford and soon filed a petition to vacate the adoption. Espinoza accused Brighter Adoptions and Quick of knowingly defrauding him of his parental rights and intentionally misrepresenting facts to prevent him from intervening. He presented as evidence the marriage certificate.

This was key to Espinoza’s argument because state law stipulates that while unmarried fathers have effectively no rights, married fathers must be notified of adoption proceedings. Still, by the time he filed the petition, the adoption had been finalized. According to state law, even if Espinoza could prove the adoption was fraudulent—because he was married to Julia and hadn’t been notified about the adoption—that alone wasn’t grounds to dismiss it.

The marriage appeared to be news to Quick, according to text messages she sent Julia. You are silly you know you can’t just rip up a marriage certificate and think that you’re divorced if you do that, she texted in July. The problem though is that on multiple documents…you denied being married multiple times…The other problem is that you are living with him like you’re married.

In the months since the adoption, Julia and Espinoza had continued to occupy the same space but barely exchanged words. She watched the kids during the day while he worked, and she left for the night once he came home. He was in a depressive spiral. He said he cant live life knowing his child is with someone else, Julia wrote Quick in July. He says I sold my baby.

While Espinoza struggled to pay his legal bills, Quick and her agency were represented by Larry Jenkins, a giant in the world of adoption law who supervises cases for Kirton McConkie. Jenkins is the longtime chair of the Utah Adoption Council’s standards and practice committee; Quick is also a member of the council. In court documents, Jenkins argued that Espinoza’s marriage was “dubious,” given that the marriage certificate had been produced that spring and it had taken him weeks to learn about the adoption. Because Espinoza had “failed to identify his alleged ‘marriage’ in a timely fashion,” Jenkins argued, he didn’t have a case.

Meanwhile, Julia and Quick continued to text. Julia had referred a pregnant friend to Quick, and, once her friend signed the adoption consent forms, Julia would get a referral bonus. I hope she has that baby soon cause i really need help getting my tahoe from the impound, Julia wrote.

Julia knew that Espinoza had hired a lawyer, and she had told him to do whatever he had to do—just keep her out of it. He does love his kids and for the most part hes a good dad to them, she texted Quick. He paid for their every need, Julia told Quick, and made sure to leave Sundays open so he could take them on outings.

Julia refused to talk about the adoption with Espinoza; inevitably, the subject resulted in explosive fights that eventually turned violent. When we spoke, Julia said that in the 10 years they’ve been together, they had “fist fought” four times. Every time, it had to do with adoption.

“I’m not saying that’s ever okay,” she said recently. “The reason I think I let it go is probably I would have done the same thing if someone was giving up my kids and I couldn’t do anything about it.”

She repeatedly confirmed that she didn’t choose adoption because she was scared. “He don’t hit his kids,” she said. “He loves those kids.” She added, “It’s not a situation where I’m walking on eggshells because I think he’s gonna beat me up. I wouldn’t put up with that.” (Asked about the fights, Espinoza wrote in an email, “I love her and I love my kids.” He added, “I don’t think I’m a violent person.”)

In February 2021, Quick was deposed in Espinoza’s case. The deposition, which lasted nearly two hours, gave a rare glimpse into the adoption industry in Utah. Quick estimated that of 150 adoptions the agency had completed in the last three years, just five birth moms were local. Asked if Julia ever indicated that she wasn’t telling the truth, Quick replied, “Oh jeez, I don’t know that any of my birth moms are truthful people, but she didn’t—I mean, she was a typical birth mom.” Asked what, if anything, Brighter Adoptions does to ensure that birth mothers aren’t married, Quick said, “We take the birth mother’s word.”

During the deposition, Quick interrupted to ask if she could take a look at her phone. It was blowing up, she said, and she wanted to make sure nobody was in labor.

In the summer of 2021, Espinoza couldn’t keep up with his legal bills, and his lawyer withdrew. That November, the case was dismissed.

Just a few hours before a judge dismissed the case, Quick sent Julia $375 over Cash App. It wasn’t a late payment from her pregnancy a couple of years before: Julia was pregnant again. This time, she says, she really did plan to keep the baby—but still, she approached Quick.

“I knew that she would take care of me while I was pregnant,” Julia told me. “I just knew that she would give me money.”

Notes from Cash App transactions suggested a similar dynamic between Quick and Julia the second time around: Julia shuttled between Las Vegas and Utah, hitting up Quick for money for things like gas, tires, and motel stays. Quick, with increasing alarm, urged Julia to return to Utah in messages like, where are you!?????!!!!!!! And stay in hotel!!!!!!!! Love you!!

Over four months of Julia’s pregnancy, Quick paid her nearly $7,000, according to Cash App transactions.

One payment, in December 2021, stands out: $354 for “suboxone 60 strips,” indicating that Quick paid her directly for the opioid addiction medication.

When Julia arrived at Centennial Hills Hospital in Las Vegas to give birth, she still planned to keep the baby, even though she didn’t feel ready. But when hospital staffers woke her up to take her blood pressure, they noticed heroin on Julia’s pillow. She’d fallen asleep with it in her hand. Spooked that the police might get involved, Julia ran—and made her way to Utah.

Espinoza sent a desperate email to Utah’s Division of Child and Family Services. “I’m trying to fight for my kid pls help me,” he wrote.

The baby boy was born at the same Utah hospital where Julia had delivered two years earlier. Julia signed forms consenting to the adoption the next day to Mary and Perry, the same couple who had adopted her other son.

Espinoza estimates that he called the hospital more than 100 times during Julia’s stay, until a nurse put him through to her room. Quick picked up the phone and hung up on him, he says. (“We provide legally required notice to birth fathers,” Quick said, and “follow applicable laws regarding birth father rights.”)

In the days after Julia gave birth, Espinoza reached out to every regulatory agency he could think of. He called the police. He sent a desperate email to Utah’s Division of Child and Family Services. “How can I stop a adoption I’m the biological father the agency hide everything from me that agency offer money to send mom’s there,” he wrote. “I’m trying to fight for my kid pls help me.” He sent a similar email to a local news channel. But these efforts didn’t get him anywhere.

He again tried to sue for custody. This time, he represented himself. With broken English and no legal background, he struggled to navigate the bureaucratic maze. (“Can you please tell me what paper that needs to fill out to stop the adoption process?” he wrote a judicial assistant that February. She referred him to the Self-Help Center.) The case was later dismissed.

Espinoza and I first spoke this past spring, after I had come across his case in Utah’s court records system. He emailed back within hours. “I’ve been looking for this opportunity to find somebody to make it public about…about them buying kids,” he said on the phone. His voice cracked when he talked about how the older children, now 6 and 9, vaguely know that their family isn’t complete.

In the months that followed, we stayed in touch. Julia agreed to talk, too. After everything, Julia and Espinoza still live together, with their two older kids. Julia’s ambivalence over the second adoption was palpable, her speech filled with unfinished sentences and interjections. “I don’t know why I did it again,” she said. “It’s just a hard situation to explain.” She said of Espinoza: “I do love him, and even Sandi knew. She knew I loved him.”

“If I had to do it all over again, I probably would have kept the kids,” Julia concluded. “Both of them.”

Eventually, I had a hard time reaching Espinoza. He wanted to share his story, he wrote in an email, but thinking about the adoptions was making him depressed all over again. It was, he said, like pressing on an injury.

“IDK how to explain this feeling,” he wrote. “I just cant be ok without my kids.”

If he wanted to, Espinoza could watch his children grow up—in the photos Mary posts on Facebook. There, the kids, now 5 and 2, play at the beach, in the snow, on the sidewalk. The 5-year-old has Espinoza’s round face. The 2-year-old has Julia’s big eyes. Friends comment on how much the kids have grown, how beautiful they are. The family, they say, is so blessed.