AFP

AFPFor nearly 300 years, a family’s ancestral house in India’s southern state of Kerala has been the stage for theyyam, an ancient folk ritual.

Rooted in ancient tribal traditions, theyyam predates Hinduism while weaving in Hindu mythology. Each performance is both a theatrical spectacle and an act of devotion, transforming the performer into a living incarnation of the divine.

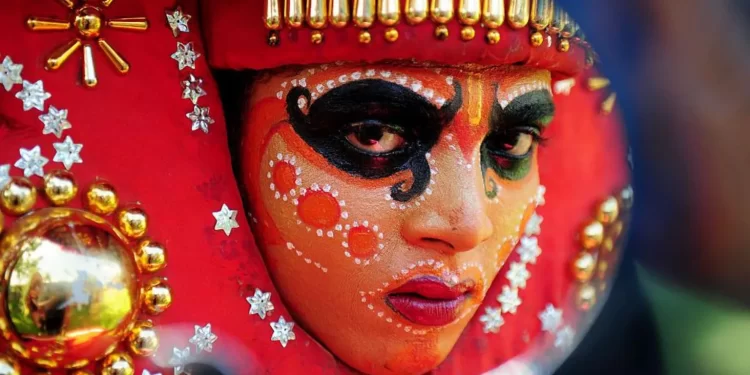

The predominantly male performers in Kerala and parts of neighbouring Karnataka embody deities through elaborate costumes, face paint, and trance-like dances, mime and music.

Each year, nearly a thousand theyyam performances take place in family estates and temples across Kerala, traditionally performed by men from marginalised castes and tribal communities.

It is often called ritual theatre for its electrifying drama, featuring daring acts like fire-walking, diving into burning embers, chanting occult verses, and prophesying.

Historian KK Gopalakrishnan has celebrated his family’s legacy in hosting theyyam and the ritual’s vibrant traditions in a new book, Theyyam: An Insider’s Vision.

He explores the deep devotion, rich mythology, and surprising evolutions of the art, including the rise of theyyams performed by Muslims in a tradition rooted in tribal and Hindu practices.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanThe theyyams are performed in the courtyard of Mr Gopalakrishnan’s ancient joint family house (above) in Kasaragod district. Hundreds of people gather to witness the performances.

The theyyam season in Kerala typically runs from November to April, aligning with the post-monsoon and winter months. During this time, numerous temples and family estates, especially in northern Kerala districts like Kannur and Kasaragod, host performances.

The themes of performances at Mr Gopalakrishnan’s house include honouring a deified ancestor, venerating a warrior-hunter deity, and worshipping tiger spirits symbolising strength and protection.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanBefore the performance honouring a local goddess, a ritual is conducted in a nearby forest, revered as the deity’s earthly home.

Following an elaborate ceremony (above), the “spirit of the goddess” is then transported to the house.

Mr Gopalakrishnan is a member of the Nambiar community, a matrilineal branch of the Nair caste, where the senior-most maternal uncle oversees the arrangements. If he is unable to fulfil this role due to age or illness, the next senior male member steps in.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanWomen in the family, especially the senior-most among them, play a crucial role in the rituals.

They ensure traditions are upheld, prepare for the rituals, and oversee arrangements inside the house.

“They enjoy high respect and are integral to maintaining the family’s legacy,” says Mr Gopalakrishnan.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanThe spectacle is a blend of loud cries, fiery torches, and intense scenes from epics or dances.

Performers sometimes bear the physical toll of these daring feats, with burn marks or even the loss of a limb.

“Fire plays a significant role in certain forms of theyyam, symbolising purification, divine energy, and the transformative power of the ritual. In some performances, the theyyam dancer interacts directly with fire, walking through flames or carrying burning torches, signifying the deity’s invincibility and supernatural abilities,” says Mr Gopalakrishnan.

“The use of fire adds a dramatic and intense visual element, further heightening the spiritual atmosphere of the performance and illustrating the deity’s power over natural forces.”

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanThe deities can be manifestations of gods and goddesses, ancestral spirits, animals, or even forces of nature.

Here, the theyyam performer (above) embodies Raktheswari, a fierce manifestation of Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction.

She is portrayed drenched in blood, a powerful symbol of her raw energy and destructive force.

This intense ritual delves into themes of sorcery, voodoo, and divine wrath.

Through dramatic costume and ritualistic dance, the performance channels Kali’s potent energy, invoking protection, justice, and spiritual cleansing.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanDuring the performance, the artist (or kolam) transforms into these deities, through elaborate costumes and body paint, their striking colours bringing the deities to life.

Here, a performer meticulously adjusts his goddess attire, checking his look in the mirror before stepping into the ritual. The transformation is as much an act of devotion as it is a preparation for the electrifying performance ahead. KK Gopalakrishnan

KK Gopalakrishnan

Distinct facial markings, intricate designs, and vibrant hues – especially vermillion -define the unique makeup and costumes of theyyam.

Each look is carefully crafted to symbolise the deity being portrayed, showcasing the rich diversity and detail that distinguishes this ritual art. Some theyyams do not require face painting but use only masks.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanTheyyam’s animistic roots shine through in its reverence for nature and its creatures.

This crawling crocodile theyyam deity symbolises the power of reptiles and is venerated as a protector against their dangers.

With its detailed costume and lifelike movements, it highlights humanity’s deep-rooted connection to nature.

KK Gopalakrishnan

KK GopalakrishnanSometimes the deity will bless a large congregation of devotees after a performance.

Here, a female devotee unburdens her troubles before Puliyurkali, a powerful manifestation of goddess Kali, seeking solace and divine intervention.

As she offers her prayers, the sacred space becomes a moment of spiritual release, where devotion and vulnerability intertwine.