Select public screenings of All We Imagine As Light, the second feature from rising Indian filmmaker Payal Kapadia, began in early May, a few weeks ahead of the film’s splashy competition debut at the Cannes Film Festival. I first saw the film during this run in London at the notoriously dingy Soho screening rooms and as the credits rolled in the room, there was a feeling of subdued excitement in the air. Attendees — some of the industry’s most hardened and cynical critics — could be seen cracking smiles at each other and nodding approvingly.

It was clear that everyone in the room had realized they’d seen something rather special, but no one dared to make pronouncements about its potential. I suspect in part due to the volatility of a Cannes debut. Films by much bigger names, traditionally sure-fire locks with the chin-scratching Riviera crowd, have opened on the Croisette and disappeared faster than you can say Palme d’Or. There was also the structural question. Can a film of this scale and radical ambition, produced in India in the Malayalam language, and directed by a woman, cut through? The answer was a resounding and refreshing yes. Following a historic competition win in Cannes, All We Imagine has enjoyed acclaimed bows at NYFF, London, Tokyo, Chicago, Denver, San Sebastian, Mill Valley and Sydney, to name but a few.

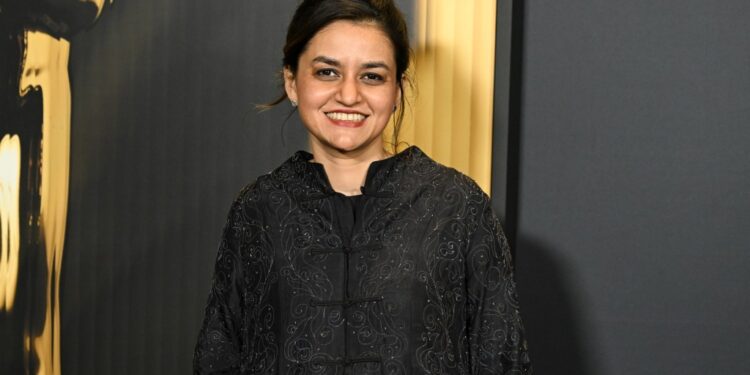

“It’s all so exciting,” Kapadia tells me from the bright offices of Janus Films just off Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. The company picked up All We Imagine out of Cannes and began a limited release stateside on November 14. The flick has been a consistent sellout since then, clocking Janus it’s best-ever opening at the box office.

“When you make a film, the nicest thing is that it gets shown and you just hope people go to watch it,” Kapadia continues.

All We Imagine As Light now enters the awards season as one of the year’s strongest and most popular titles. Before campaigning officially starts, however, Kapadia must return to her native India where she will launch a nationwide release. She tells me she’s “a bit nervous” about returning home with the film.

“It’s not easy to release a film like this in India. In Kerala, I think it might be an easier sell because it’s a film in the Malayalam language, so they won’t need to read subtitles,” Kapadia says. “There is also a connection with the actors there because audiences recognize them. They’ve become household names.”

Kapadia describes the Indian cinematic landscape as a large and diverse “self-contained system.” Local audiences aren’t so fussed with awards and acclaim out of Cannes. The National Film Awards of India can pull a crowd and local audiences may take a second glance at an Oscar. But the most useful commodity, Kapadia says, is local notoriety.

“The local films that may come out in Kerala in Tamil are the films people actually anticipate,” Kapadia says. “It’s still all about your local cinema and what film is coming out there. The local actors you love and turn up for and the local directors who inspire you. It’s a very self-contained system.”

Shot over 25 late summer days in Mumbai, followed by an extra 15 in the rainy western port town of Ratnagiri, All We Imagine As Light tells the story of two young women — Prabha, a nurse from Mumbai, and Anu, her roommate. A rare French-Indo co-production, the film is a collaboration between the Paris-based producers Thomas Hakim and Julien Graff, of Petit Chaos, and Zico Maitra of Chalk & Cheese Films out of Mumbai.

All We Imagine as Light is the first feature from Maitra’s Chalk and Cheese after nine years of primarily producing commercials for television and digital media. Hakim and Graff are a buzzy-producing duo widely recognized across the European festival circuit for an impressive range of short and feature projects.

“It was like an extended family across two continents, and we really grew close,” Kapadia says of her collaboration with Hakim, Graff, and Maitra.

Below, Kapadia shares some further insights about the production behind All We Imagine As Light, how she has navigated the film’s rapid success, and what she made of the film being snubbed as India’s submission for the Best International Oscar race by India’s Film Federation. Kapadia also shares some details about her next feature project.

DEADLINE: Payal, how are you?

PAYAL KAPADIA: I’m good. I’m super excited. The film was released this week in America and we open on November 22 in India. I wasn’t so sure we’d get Indian distribution because it’s not easy to release a film like this in India. A lot of films, even the big ones, don’t always do well in the theaters. So I was a bit nervous that I wouldn’t get a distributor. But because of this whole Cannes thing, there were a lot of distributors who were interested, and even exhibitors who were willing to book the film.

DEADLINE: The film has been traveling all over the world. Where have you had the best screening so far?

KAPADIA: I think the film had a pretty great screening in the UK. I wasn’t there for that one, but Kani, my actress, was there and she said the audience was really taken with the film. We also had a really good screening here at the New York Film Festival, which was amazing. The wildest screening was in Mumbai. We opened the Mumbai Film Festival. It was in this old cinema, which is a famous Mumbai artifact. It’s called Regal Cinema. It’s an old-school single-screen cinema with a balcony and dress circle. The sound is awful. They have all the fans on because it’s so hot. But it was still so nice because the film was finally screened in Mumbai, where it was shot.

DEADLINE: You’re returning to India to release the film. The funny thing about having international success is that you often become the face of your home country on a global scale even if you might have a complicated relationship with where you come from. It’s a sort of weird nationalism people bestowed on you. How have you felt about that?

KAPADIA: We have a very large ecosystem of films. So the local films that may come out in Kerala in Tamil are the films people actually anticipate. It’s still all about your local cinema and what film is coming out there. The local actors you love and turn up for and the local directors who inspire you. It’s a very self-contained system. So I wouldn’t call myself the face of Indian cinema in that sense. People are still discovering that there’s this festival in France that happens every year and it’s somewhat a big deal. The national awards in India hold a lot of importance. People may know the Oscars a little more than Cannes. But still, it’s more about your local cinema and which film is coming out there and the actors and directors you enjoy. India is a very self-contained system.

DEADLINE: It’s also interesting how the film industry has embraced this film. All We Imagine is a very political and radical film. So is your first feature A Night Of Knowing Nothing. But All We Imagine is now mostly only discussed in terms of its aesthetics. Critics talk about its beauty. Or they identify the film’s politics only in relation to India but fail to make the connection with their own lives. Have you noticed that? What do you think about it?

KAPADIA: I’m always concerned about this when I’m writing a film, and it’s related to myself as a filmmaker with a certain amount of privilege. I can go on about formalistic ideas in cinema, but at the end of the day, there needs to be a balance between these bourgeois ideas and the film’s themes. I’m negotiating this all the time as a filmmaker. Now, the angle you are discussing is the viewing of the film. And in that sense, I feel there is a bit of an advantage, because sometimes if the film’s form is attractive or can mesmerize an audience, but you can also sneak in pertinent political themes, that’s interesting to me. But it’s a fine line and I’m always trying to balance that in my head.

DEADLINE: This film is very invested in cinematic language. The narrative is advanced by what we see and hear, not necessarily dialogue. With that in mind, how do you write screenplays? What do your scripts look like?

KAPADIA: When I first started writing the screenplay I wrote very detailed descriptions of the colors and the sound in the film because they do a lot for the film’s narrative. There are certain things you can’t describe with words that, to me, rely on sound. So that becomes very tricky to write into a script. It took me a while to understand how to become a more efficient writer, which was important. At the end of the day, the people who are going to commission your film are reading thousands of scripts. They’re not going to want to read this descriptive essay on what the sounds of Mumbai feel like. So it took me some time to distill that. My producers had a big role to play in distilling some of those ideas and giving me a push. And, to be honest, the commissioning system is pretty good because you can get a script greenlit, but after that you have a lot of flexibility in the production. So I took a lot of liberties at that stage.

DEADLINE: When did you first know you wanted to be a director?

KAPADIA: I actually had very little respect for what it was to be a director. There’s this whole attitude in India where the directors are just brooding men walking around. So I wanted to be an editor. I felt that was something concrete, and I understood what everyday life would be like as an editor. I was fascinated by editing as a craft. My mother is an artist and she made video work quite often. And the editing she did was the first piece of the filmmaking process I saw being done. After that, I started looking at films, like big Hollywood films, and saying, ‘Ah, I see what was done here.’ At that point, it felt like a new world had opened up to me that no one else could see. Obviously, that was not the case, but I felt like I could really see things. So I wanted to be an editor. I applied to the film school right after college and didn’t get in. I was really disappointed and didn’t know what to do with my life. At the time, it was easier to get jobs as an assistant director, so I started working and that’s when I started discovering what directors did and how they created their visions. So I applied to film school again for directing and was accepted.

DEADLINE: Your first film A Night Of Knowing Nothing won the Best Documentary prize at Cannes in 2021 and I remember it screening at a bunch of festivals too. Why do you think you’ve blown up now with this film?

DEADLINE: You’re going to hate this question but I have to ask about the Indian Oscar committee. Of course, they didn’t choose your film. But more interesting to me was their reasoning. They said All We Imagine As Light wasn’t Indian enough. What do you think they meant by that?

DEADLINE: Yeah, it’s bizarre. I interpreted their comments to mean that because the film has an avant-garde structure its maybe more European, which is bizarre because that avant-garde structure has stronger origins in Asia than anywhere else.

KAPADIA: Exactly, it’s very Asian. Anyway, the whole committee with 13 men is also quite bizarre.

DEADLINE: When will you be done promoting the film and be able to go home?

KAPADIA: By the end of December. The main releases will be over with the UK, U.S., Spain and India. At that point, I hope to chill and start working on another film.

DEADLINE: Do you know what the film will be?

KAPADIA: It’ll be a film set in Mumbai. But with the distribution of this film in India especially, I’ve increasingly been thinking about questions surrounding form like the one you brought up earlier. I want to understand where I as a filmmaker fit in the cinematic landscape of this country where it’s not always easy to distribute films like All We Imagine As Light. This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot recently. I’ll have to find that balance between formalistic choices and accessibility from an Indian context.

DEADLINE: Are you saying in an eloquent way that you’re thinking of changing your approach to filmmaking to make your films more accessible to wider audiences?

KAPADIA: I feel a balance can be found. One can stick to one’s cinematic intentions and still perhaps make certain choices that make the structure more recognizable for audiences. You can play around a lot with your politics and your cinematic intentions. I feel like that is a more interesting challenge for filmmakers. So let’s see. American filmmakers do this a lot because it’s always been a struggle to create certain types of films here. It’s all about navigating the structures of the system while keeping your love for cinema and the kind of cinema you love intact.