A caution to readers: This story is an unvarnished, unsanitized firsthand account of the Second Battle of Fallujah that includes descriptions and photos that are candidly disturbing. In telling this story, I promised my fellow Marines that I would not sugarcoat our experience. This story is published in collaboration with The War Horse.

Narrow metal cages sit empty in a dark, damp corner of the execution room. Bloody handprints mark the windowless mud walls. Human feces are piled in the corner. The air smells of urine and death.

Nearby stands a makeshift altar. Dried blood stains the dirt beside an empty camera tripod. The floor feels tacky with every step. A Quran rests on a lectern. Knives and medical supplies are strewn about the ground. The black flag of Al Qaeda hangs on the wall.

Some of us step outside. Others argue over whether the bloody handprints belong to the victim or the executioner. Some guess how many heads had rolled across the floor, or whether the executioner used the straight-edge or the serrated knife. Did they prefer efficiency or pain? The dark humor dulls our reality and makes the scene more palatable. It’s 2004, roughly 10 days before our families back home will celebrate Thanksgiving. As our squad of Marines resumes our patrol through Fallujah, Iraq, some of us pledge to kill ourselves—and each other—before we will ever be caged by the jihadis. Every conversation circles back to the cages and the killing. A few Marines struggle to eat dinner. Country Captain Chicken looks even less appetizing. The thought of being trapped in a cage keeps me awake.

For the next month, combat strips away our humanity as we patrol street by street. Combat brings out the absolute best and worst in us. Most laugh about the death. The ones who break down are sent back to the base. Others photograph corpses and detainees. A few volunteer to kill the dogs feasting on human remains. With every firefight, we drift further from the values we once held dear and the men we once were. Fathers and sons. Blue-collar workers and college graduates. And even the pompous son of a billionaire.

All changed forever by war.

After five weeks in Fallujah, it seems like many of us have lost our way and are not fazed by the depravity surrounding us. Some of us laugh at a kitten crawling out of the chest cavity of a corpse, and after one of my rockets transforms a human being into a bloody shadow on a wall.

Most of us celebrate the crumpled bodies, mangled by the rockets and bombs. Some photograph the corpses bursting like combat pinatas after bloating under the desert sun. We cheer as a bulldozer buries enemy fighters alive.

The dozer is bulletproof. We aren’t. And we’ve all rationalized that they are going to die anyway.

Then, one night shortly after Thanksgiving, we are awakened by the sound of a Marine from another battalion beating a cat to death against a wall. He releases its lifeless body from the empty green sack, and it falls from our second-story window onto the street below. The animal was making too much noise, he says. He then lays down beside us.

We all go back to sleep.

It’s been 20 years now—half our lifetimes—since we fought in the bloodiest battle of the global war on terrorism. President George W. Bush had just won reelection, despite concerns over the Iraq War and the lies that led us there. It had been 18 months since he had declared “an end of major combat operations” in Iraq.

But the insurgency was growing stronger. Militants boobytrapped roadways with explosives and beheaded Iraqi collaborators in kill rooms—like the one we discovered—executions that were filmed to send a message both to the Iraqi citizens and foreign invaders. But nothing symbolized the disdain for our presence in Iraq more than the March 2004 execution of four US contractors from Blackwater who were beaten, lit aflame, dragged behind vehicles, and hung from a bridge in Fallujah. At the time, I was an 18-year-old Marine fresh out of boot camp who didn’t know any of that story. But seven months later, here I was, in November 2004, as one of nearly 13,000 American, British, and Iraqi forces ordered to fight Operation Phantom Fury, a 46-day battle during the US occupation of Iraq and the heaviest urban combat Americans had seen since the 1968 Battle of Huế City during the Vietnam War. The battle demonstrated that what we thought a year ago were pockets of resistance was, in fact, a full-blown insurgency.

More than 4,000 enemy fighters armed with rockets, machine guns, and explosive devices fought from trenches, tunnels, and booby-trapped homes.

By the end of the battle, about 110 members of coalition forces were killed and more than 600 were wounded. Roughly 2,000 enemy fighters died, and 1,500 were captured. An estimated 700 civilians were killed, and by the end of the battle, nearly half of the city lay in ruins. It marked a new phase in a war that was quickly spiraling out of control and would ultimately cost US taxpayers more than $728 billion and lead to the deaths of more than 4,500 coalition troops and more than 32,000 others wounded. In total, at least 200,000 Iraqi civilians were killed.

For 20 years, the men and women ordered to fight in Fallujah—and other battles of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—have lived with those traumas, and despite our collective successes as we continued serving or returned to civilian life, many of us still ended up in a box.

The moral injury. The drugs. Alcohol. Suicide. Divorce. Cancers from the poisons we were exposed to. The list goes on and on.

For the last two decades, I have avoided reading the books that were written about our battle. I haven’t watched the documentaries or revisited the news stories. I distanced myself from the reunions and the young men who were once my close friends.

As I write this, I have tears in my eyes. I’m afraid of what this journey will do to me and what the reaction will be. But the further I travel in life beyond the house-to-house fighting, the more I wonder how my body—and my mind—survived it, and whether I still will.

Everyone back home expected us to be killers and diplomats at the same time. We succeeded on the former and failed tragically on the latter. If I were a resident of Fallujah who returned home to the destruction after our battle, I would commit my life to killing Americans.

We didn’t just destroy the enemy, we thrived at it. And many of us grew to enjoy it. Yet we obliterated parts of ourselves along the way.

We defecated in people’s bathtubs to avoid being shot in the street. My rockets broke prayer beads and incinerated Qurans. Grenades blew apart heirlooms. We destroyed wedding photos as we knocked over dressers and flipped mattresses during our searches. Across the city, Marines set homes ablaze. We littered neighborhoods with white phosphorus, unexploded ordnance, and burn pit ash. We blew up childhood bedrooms, schools, and mosques.

The destruction was a tactical necessity. But it was also fun.

Two decades on, I now carry a heavier pack: the guilt that I could have done less. And more. For 20 years, I’ve wished I had fired a rocket into an enemy stronghold instead of letting Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth kick in that door. And for 20 years, I haven’t stopped thinking about the time we were ordered to stand down and not shoot a group of enemy fighters using women and children as human shields. The jihadis scurried down an alleyway.

Our collective wish list of do-overs is neverending. But the list of selfless and heroic acts we witnessed in Fallujah is also endless.

Before Fallujah, I thought I understood war. Bullets and blood. Bodies and bandages.

Some live. Some die. Oohrah.

But what combat teaches you is that your circle shrinks to the handful of people who are there with you. Nobody and nothing else matters. Not the flag. Not our families or fellow Americans back home. Not a fictional hunt for weapons of mass destruction. Not the Iraqi people. And surely not the politicians who sent us to war. We were ordered to fight and did whatever we had to do to survive. This is our story.

Marines are wounded. I rush to pick up the handset of the radio and begin calling in a casualty evacuation. Location. Callsign. Number of patients.

I can’t remember what to do or say next. I’m caving under the pressure.

“You’re a piece of shit, and you’re going to get everyone killed,” screams my squad leader, Sgt. Billy Leo, a 27-year-old from the Bronx.

“You’re a piece of shit, and you’re going to get everyone killed.”

I’m 6,000 miles from the battlefield, and I’m making a great first impression.

It’s 2004 and I’ve just graduated from the School of Infantry, and this is my first training exercise as one of 3rd Platoon’s newest “boots,” the most junior Marines in the Corps. I’m an infantry assaultman specializing in demolitions and rockets, and I’m assigned to Alpha Company, one of four infantry units within 1st Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

In fewer than 90 days, we will be patrolling the streets of Iraq together for seven months. I quickly learn—and Sgt. Leo reinforces—that I am not ready for combat and that I haven’t earned his trust.

The rest of my week is a blur of standing guard, filling sandbags, exercises in the treeline, and whatever other “fuck fuck games” could be played to teach me—and my fellow “hopeless” boots—a meaningful lesson: Lives depend on proficiency, attention to detail, and an instant willingness to follow orders.

When we wrap up our two weeks in the field, we’re shipped off to an abandoned Air Force housing complex near San Diego known as Camp Matilda—a wasteland of asbestos and lead-based paints, broken glass, and rusted metal.

For weeks, we practice setting up vehicle checkpoints, searching detainees, and rehearsing infantry tactics we’ll soon use in Iraq. At night, I lay on the floor of an abandoned home and stare at exposed insulation in the ceiling as I fall asleep.

After two months with my Marines, I travel back to the Boston area for 30 days of pre-deployment leave back at my childhood home, where my friends from high school tell me I’m crazy if I go to Iraq. They’re supportive of my service, but my enlistment has always confused them, and they can’t fathom trusting strangers with their lives. I tell them that Sgt. Leo is one of the big reasons why I do.

He’s a towering force with a contempt for arrogant leaders and is fiercely loyal to us. I barely know him, but I trust him. He’s bar-battered and constantly goes toe-to-toe with higher-ups to defend us from their flawed strategies and pointless games.

Only he fucks with us.

Deep down, we know Sgt. Leo just wants to bring us all home.

Back in North Carolina, we lay our uniforms on the ground in the quad at the center of our barracks. Marines with canisters of chemicals walk back and forth and mist our clothing.

The chemicals are to protect us from malaria and last the entire deployment, they say.

Wash your uniforms twice, and they are safe to wear, they say.

The next day, and nearly every day until we deploy, we start our mornings on that same grass. Pushups. Situps. Grappling matches. Then we put on our chemical-laced uniforms and lay out our gear over and over.

We clean our rifles and rooms. Then we clean our rifles some more.

After work in the barracks, we drink. A lot. It’s big boy rules. Underage? Doesn’t matter. Want to throw a fridge off the third story? It better be your fridge. Want to see who can smash more beer bottles on their head? Doc better not have to stitch you up.

Marines funnel hard liquor from the third story. Some hire sex workers or seek out happy endings at massage parlors. Others tell tales of past sexual conquests. Arrington brags about the size of his dick, eager to show anyone who doesn’t believe the lore. Drunkards wrestle and fight. Our “give a fuck” is broken, and all of the boots will clean up the mess before our morning formation. We are going to war.

By the end of our first month in Iraq, the monotony of the beggars, the tan landscape, and our mission to “win hearts and minds” are killing our motivation and making us complacent.

Diplomacy is the Army’s job, not the Marines’.

For our first three months in Iraq, we aimlessly patrol Rawah, Hadithah, Anah, and other small villages. At Iraqi police stations, we barter copies of Playboy and Hustler for fresh meals of chicken and rice. In each city, we are itching for a gunfight, but all we do is kill time. The only thing we are fighting is boredom.

None of us has lost our combat virginity.

In late October, we’re told we’re getting a change of scenery and to pack only the gear we can carry. We are being relocated to Camp Fallujah. We do as we’re told. We’re unaware of the intense fighting elsewhere in the country and that Fallujah is an insurgent hotbed where jihadis film executions.

A few days later, we strap our packs to the sides of 7-ton trucks and ride into the darkness. What seems like an endless string of military vehicles stretches to the horizon in either direction. I chain-smoke Marlboros as I stare at the stars and fall asleep to the hum of knobby tires against the asphalt.

When we get to Camp Fallujah, we all know something big is about to happen. Thousands of Marines from across multiple battalions are crammed onto the base. We repetitiously review maps, practice casualty evacuation drills and clearing rooms, and go to a makeshift rifle range to verify the sight settings on our weapons.

Our leaders know a tough fight is ahead of us, and their plan is shrouded by the fog of war and the uncertainty of violence.

A few days before the battle begins, our battalion is standing in a semicircle when an enemy mortar round slams into the ground beside our formation and doesn’t explode. I think about how lucky we were that the round was a dud. Dozens of us are standing in the kill radius. We erupt with a mix of cheers, laughter, and screams.

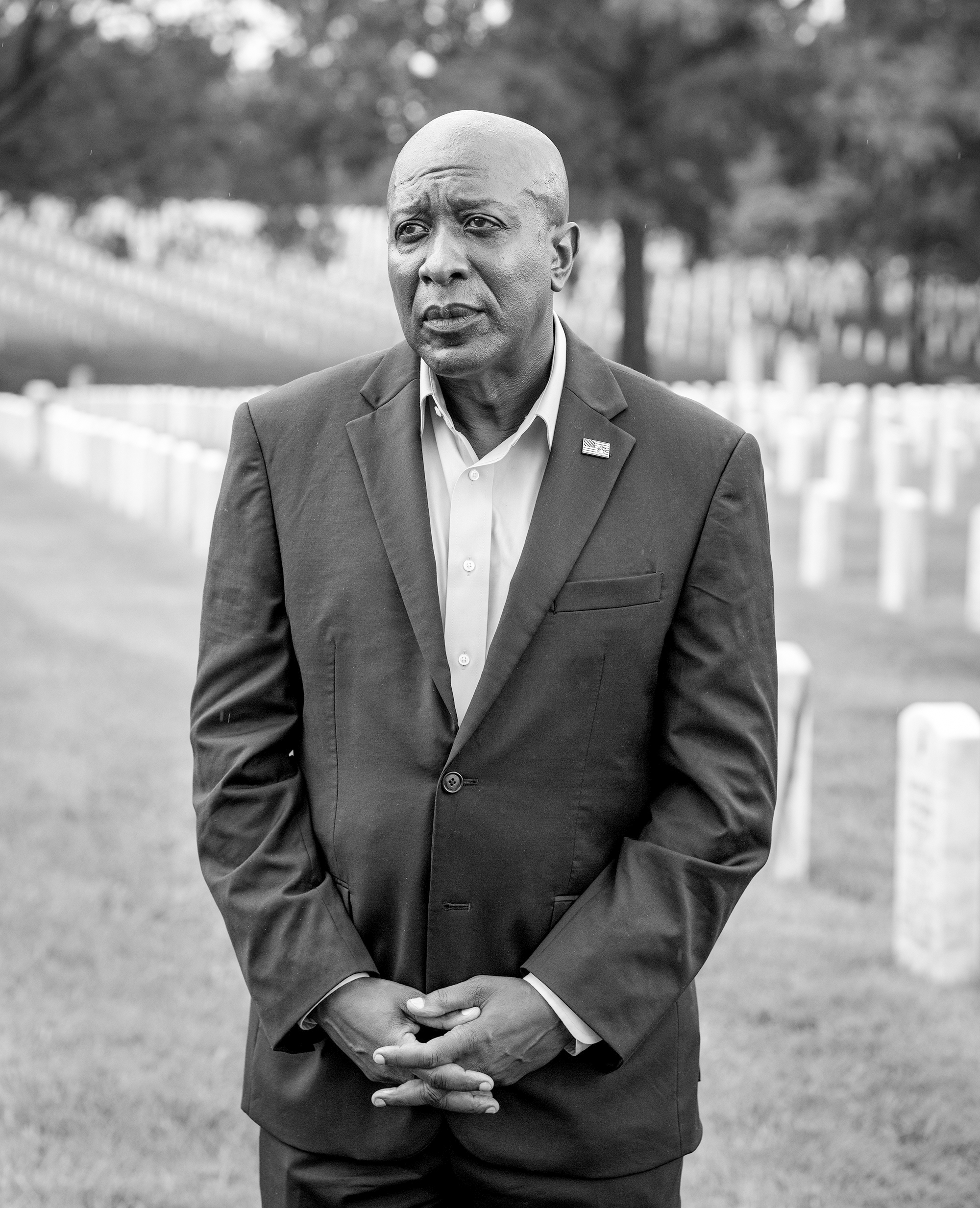

Our battalion goes silent as Sgt. Major Carlton Kent, a 47-year-old from Tennessee and the senior enlisted Marine for the upcoming battle, steps in front of us and looks out across a sea of desert camouflage. Some of us sit. Others kneel. Some stand.

“I’m gonna tell you one thing. It is an honor for me to be able to serve with each and every one of you hard chargers,” he says. “I mean, I look out here, and it’s no difference than when we took the damn war over in Korea, we took it during World War II, we raised the flag at Iwo Jima—it’s no difference.”

“It’s no difference than when we took the damn war over in Korea, we took it during World War II, we raised the flag at Iwo Jima—it’s no difference.”

“Y’all are in the process of making history, and I am very proud of you, and I have no doubt you are gonna go in there and do what you always have done—kick some butt.”

We walk back to our building and await a briefing from our platoon commander, 2nd Lt. Douglas Bahrns, a 23-year-old who studied English at Virginia Military Institute. As Bahrns walks into the room, Sgt. Leo tells us to sit down and shut up.

Bahrns stands in front of us. Grains of sand float through motionless air as beams of light creep through sandbagged windows. Young men sit mesmerized by the words echoing off walls scarred by years of war.

Through the desert confetti, Lt. Bahrns shifts between confidence and trepidation as he explains the details of our mission to clear Fallujah of enemy fighters and what should happen when—not if—we are wounded.

He tells us that inside the city, we will face roadblocks, sniper positions, boobytraps, and more than 300 well-constructed fighting positions that make up a three-ring defensive posture. He explains that civilians have fled the city, and our psychological operations teams have manipulated insurgents into preparing for an attack from the south. Instead, blocking forces will first surround the southern side of the city, and then our platoon will be at the center of a six-battalion, house-to-house battle.

Lt. Bahrns pauses often, gazing into the darkness above our heads.

The reality of our mission is becoming clear. We know that Bahrns, like Leo, wants to bring us all home. We all know that won’t happen.

The screams of thousands of US Marines roar into the distance as tracer rounds dance across the night sky, through a barrage of air-burst white phosphorus and thousand-pound bombs.

For hours, we watch as munitions explode. Some of us ooh and ahh. Others pace anxiously. As the night passes, we fall asleep to the sounds of warthogs and gunships. I cuddle with Phil Barker and Doc Frasier to stay warm.

Operation Phantom Fury is beginning.

Task Force Wolfpack is the first unit to breach the city’s perimeter, and as they begin taking sporadic fire, a voice in Arabic echoes from the loudspeakers of a nearby mosque.

“Citizens of Fallujah, stand up. The infidels are here. Kill them, kill them all.”

“Citizens of Fallujah, stand up. The infidels are here. Kill them, kill them all.”

For two days, as the first Marines push into the city, I check and recheck my gear, cinching my rockets tighter and tighter against the 20-pound satchels of C-4 inside my pack, and wait to storm Fallujah. I wonder if the combat will be over before we reach the outskirts of the city.

I draw smiley faces on my grenades and write, “One free ticket to Allah” on an explosive. I snap a photograph that captures my misguided hatred. We play grab ass and Spades, and I make dozens of donut and det-linear charges that will soon make doors disappear.

But mostly, with each explosion or machine gun burst we hear, we wonder what it will be like inside the city. Who will be the first to die?

Shortly after 3 a.m. on November 10—the Marine Corps’ birthday—we strap on our gear and load into the tracked vehicles that will be either our chariots into battle or a metal mass grave.

The diesel engines roar to life as the metal ramp closes behind us. The earth crunches beneath us as we begin our drive toward the city.

We are jostled back and forth as we crash through rubble and debris. There are explosions and gunfire in the distance. Black exhaust seeps into the troop compartment.

As the seconds pass, our 20-minute drive feels like hours. I envision scenes from the Normandy landing during World War II, where machine guns ripped through the men crammed inside the Higgins boats as the ramps lowered.

I close my eyes and wait for a rocket to tear through the side of our vehicle, transforming us into a stew of melted fat and charred flesh.

I feel trapped and helpless. I want out.

“One minute,” shouts the vehicle commander. Some of us go silent. Others hype themselves up. “Let’s kill some hajjis,” someone yells. We respond with a series of guttural screams.

Yut. Err. Kill.

But as the ramp lowers, the slow creak of the metal door is all we hear. There is near-complete silence as we run to our assigned sectors of Fallujah’s government complex.

No gunfire. No explosions. No death.

For the next few hours, I sit in a dilapidated office chair, recessed in the shadows of a second-story room of the government complex. As the sun continues to rise, the buildings to our south erupt with gunfire. I notice a man with an AK-47 poke his head around a corner.

I shoulder my rifle as he creeps around a mud wall and slowly begins to close the 200 meters between us. The clear tip of my front sight traces the center of his chest. Fear builds inside me. It is the first time my training will be tested.

I pull the trigger of my M16. The weapon’s recoil nudges my shoulder, and he crumbles to the ground. The aroma of gunpowder fills the room. I fire two more rounds into his motionless body and stare in amazement as he lies lifeless. I peer through another Marine’s rifle scope to get a closer look.

It will take years for my smile to fade.

I watch the sun continue to rise across the city’s skyline as loudspeakers blare the Marines’ Hymn through the streets.

Happy Marine Corps’ birthday, I think.

Moments later, machine gunfire and rockets begin peppering our position, and I’m ordered to the rooftop with my rocket launcher. I sprint across the roof and hunker behind a small mud wall to shield myself from the bullets whizzing by.

As I lift my head, I take in the full Fallujah skyline for the first time. Buildings stretch from horizon to horizon—a sea of tan dotted with minarets and smoldering fires. I watch as Capt. Aaron Cunningham, the maestro of our frontline symphony, stands calmly as bullets skip across the rooftop around him.

We’re surrounded by the enemy.

Then the moment we’ve feared most finally arrives. The first Marine is killed.

Lt. Daniel Thomas Malcom Jr. is dead—shot in the back while calling in artillery. Jordan Holtschulte, a Navy corpsman from a nearby platoon, tried his best to save him.

News about Malcom’s death spreads across our unit within minutes and stops me in my tracks. Before Fallujah, I’d spent four months in convoys as his driver. During our time together, I grew to respect his humility and intellect. We spoke about his sister and his favorite books—I’m ashamed to say I have since forgotten those names. I never got to tell him how much I admired him or ask him about the burden he carried leading our band of enlisted misfits.

I think about how he loved to play chess, which to him was yet another way he could train his mind to defeat an opponent. If life were a brilliancy—a deeply strategic chess combination—he made his with brevity, winning a chess game in 25 moves, his age when he was killed.

His corpse is carried to a nearby vehicle and driven away.

Javelin missiles shriek through the sky. Machine gunners fire from the rooftops. Artillery thumps in the distance moments before a thunderstorm of steel rain pours around us.

Our squad is crammed into a room at the south side of the government complex, waiting to sprint across Route Fran, the multilane highway that separates us from our 3-mile, house-to-house battle through the city.

Looking back, Route Fran was a final buffer from the real carnage and a life-altering demarcation point for all of us.

Once we crossed over, life would be different.

The change would be forever.

“One minute,” someone yells.

My heart is racing.

I’m scared.

The time passes in an instant.

Yut. Err. Kill.

Sgt. Leo takes off across the road, and we sprint behind him.

I hop over the center median and rush toward the sidewalk. Electrical wires dangle from street poles. Rubble is scattered about. A thick black smoke dances in the air.

We peer through shattered windows and broken doors as we pass by shops and offices damaged by the airstrikes and rockets.

As we rush down the first alley, second-story windows erupt with gunfire. We’re pinned down.

Some Marines break off to clear nearby houses. Cpl. Robert Day, a 24-year-old from Mobile, Alabama, sprints to the roof with his machine gun and a team of snipers in tow. Bullets whiz and ricochet around him, peppering him with chunks of brick and mortar. Day presses his shoulder into his machine gun as a fighter with a backpack full of rockets sprints down a street.

Search. Traverse. Fire. Repeat.

Simultaneously, the rest of our platoon maneuvers down the street, returning fire and bounding from position to position.

“Get those rockets up here!” Sgt. Leo screams, from the front of our patrol. He’s standing beside a compound wall and is unfazed by the firestorm surrounding us.

He’s calm amid the chaos.

I prop my launcher on my thigh as my team leader, Michael Briscoe, inserts a high-explosive rocket. Together, we sprint to the middle of the street. I prop the weapon on my shoulder and press my face against the launch tube to look through the scope.

Bullets are hitting all around us as Briscoe turns around to make sure no Marines are standing behind us.

Dozens of them are. But there’s no time for protocol.

He slaps my shoulder and screams in my ear, “Backblast area all secure! Rocket!”

Ten pounds disappear from my shoulder in an instant, and the second story of the house is destroyed.

The gunfire stops. For a moment.

The enemy takes pot-shots over and around walls as we move from one home to another. We find a network of blown-out walls, allowing fighters to maneuver from house to house. Mattresses are boobytrapped with grenades and cutouts for people to hide inside. We find tripwires and machine gun bunkers reinforced with sandbags.

Sgt. Leo often takes point alongside Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth, clearing almost every home we go into. He lobs grenade after grenade over compound walls and has me blow open door after door with explosive charges. Across the street, Gary Koehler gets shot in his leg, and Matthew “Doo Doo” Brown is shot in the buttocks like Forrest Gump. Then Brian Passolt takes a machine gun burst to the stomach.

Back home, the three of them aren’t yet old enough to buy a six-pack of beer.

They’re stacked into the back of a vehicle like a cord of wood and disappear into the distance.

By nightfall, we’re still clearing our first street inside the city and occupying a house for the night. Some sleep in beds, others on pillows and piles of clothes. I am relegated to the rooftop with the boots and sleep beneath a blanket of stars between hour-long shifts of guard duty.

The next morning, we wake up before sunrise and continue our weeks-long journey south.

Eat. Sleep. Shoot. Shit. Repeat.

For days, the firefights are constant as we clear house after house. Machine gunners fire from the hip as we rush down streets. I fire dozens of rockets and we use so many grenades that we run out. I begin to prime sticks of C4 for us to throw instead. The blasts break prayer beads and tear Qurans.

In the moment, destroying heirlooms and wedding photos during searches and defecating in bathtubs to avoid being exposed to enemy fire outside feel necessary. But they’re some of the things that bother me most 20 years later.

At one point, an officer specializing in chemical weapons identification tells us that we’ve discovered drums of chemical weapons known as “blood agents” and that we should vacate the premises. We do as we’re told. We also discover a torture chamber. Decades later, I still have nightmares where I’m trapped in that small metal cage.

One morning, our patrol stops at the edge of an open field. We’re ordered to run across, and one by one, we sprint hundreds of meters toward a cluster of three-story homes.

One hundred pounds of rockets and explosives press into my flak jacket as I rush across the uneven ground, dodging ankle rollers, barbed wire, and mounds of dirt.

Puffs of dirt jump from the ground as bullets snap and whiz around us as our boots suck into the wet earth.

The charging handle of my rocket launcher digs into my thigh with every step.

My gasps for air drown out the noises around me.

Somehow, we all make it.

We climb the stairs of the building, and the squad man’s defensive positions on every floor. The Marines on the roof take cover behind a short wall and begin to return fire as enemy fighters take pot-shots from nearby windows and scurry through alleyways.

Our lieutenant quickly realizes we’re at a tactical disadvantage. We’ve been holding our position for too long, and the enemy has surrounded us on three sides.

Shell casings pile up at our fighting positions as enemy tracer rounds penetrate the wall and dance across the rooftop until they fizzle out. Talking machine guns play a game of insurgent whack-a-mole. I watch fixed-wing aircraft drop bombs in the distance.

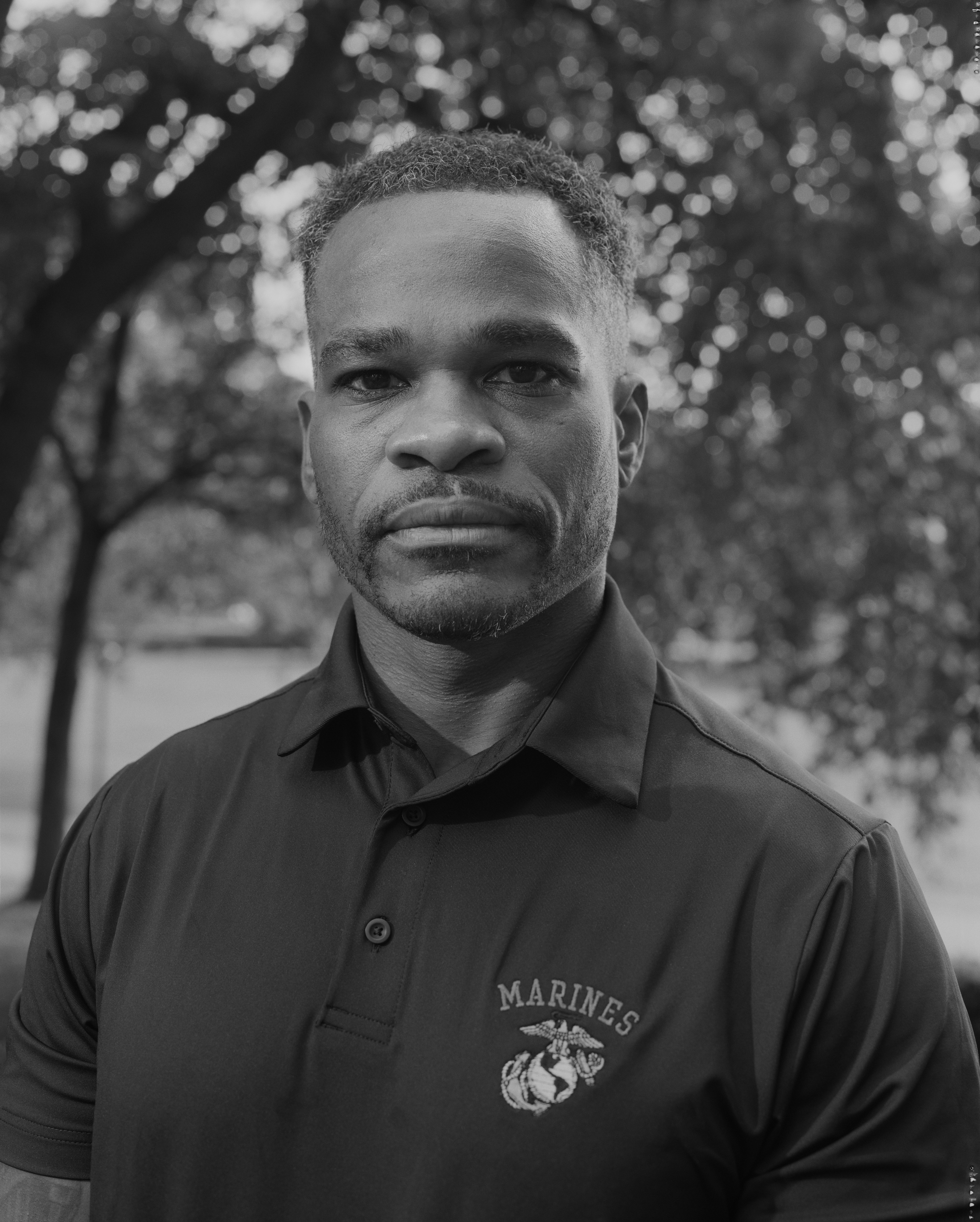

Mike Ergo, a 21-year-old from Walnut Creek, California, who joined the Corps to play the saxophone, is on the roof smoking a cigarette and scanning for enemy fighters when he hears a whoosh as a volley of rockets slams into the front of our building. The blast briefly knocks him unconscious.

As Ergo pulls himself off the ground, he sees the wall beside him is destroyed. He hears gunfire and tastes explosive residue.

“I’m hit,” Sgt. Leo screams from nearby, as the wall explodes around him. He clutches his leg. A deep purple bruise quickly spreads across his hip and thigh. Then Sgt. Nathan Fox, a 21-year-old from Berryville, Virginia, takes shrapnel in the shoulder. Ergo and another Marine rush to drag them from the roof.

I watch as our wounded are carried downstairs. Leo objects the entire time. He’ll walk it off, he jokes. Our lieutenant worries Leo’s femur is broken and forces him to leave, assuring him he’ll return soon.

For the first time, we see fear in Leo’s eyes.

As the firefight continues, our wounded are driven to the hospital. Morale crumbles. There’s an obvious void as we continue to push through the city.

Sgt. Leo was more of a security blanket than we’d realized.

We are on an afternoon patrol when I see a Marine from another battalion diddy bopping with a gnawed femur and pelvis resting over his shoulder as though he were a combat bindle stiff.

“Look at how small his dick is,” he jokes as he tosses the remains on the ground. I wind my disposable camera and snap a photograph of him bent over, smiling beside the bloody genitals. When I look at the photo now, the Marine stares back at me from underneath his kevlar helmet. His face is full of joy. At the time, I was happy, too. Two decades later, I feel contempt toward our indignity.

We’ve been inside Fallujah for weeks and have embraced the kill-or-be-killed reality surrounding us. When we see Marines from mortuary affairs begin collecting enemy remains for intelligence gathering at The Potato Factory—the section of the government center where enemy bodies are being collected—I watch from a distance as limbs deglove and meat sloughs from bones. The aroma of bloated, rotting corpses and firefights has become our norm.

We’re absent of emotion and humanity. Numb.

But now Marines across Fallujah are ordered to go on patrol and kill the animals roaming the streets.

Dogs are sick from eating the decomposing bodies, and we’re told the executions are to prevent the spread of disease.

Killing animals is a line I won’t cross. Hearing their helpless yelps and screeches is unbearable. But watching them run toward us for help once they’re wounded is torturous.

A few days later, we begin taking fire from a second-story building and quickly surround it.

The enemy is trapped inside.

A rocket is fired. Machine gunners sprinkle ammunition through windows and doorways. Others hurl grenades. The jihadis on the other side do the same.

I scream degrading comments about Islam, devoid of the shame that will metastasize.

Our interpreter—an Iraqi citizen from a village outside of Baghdad—yells for the fighters to put down their weapons and come out with their hands up.

They refuse.

We try to convince them with another volley of grenades, gunfire, and slurs about Islam.

Then a Marine runs over to the driver of a nearby D9—a 54-ton bulldozer—and asks them to demolish the house so we won’t have to go inside.

The ground shakes as the driver positions the vehicle a few feet from the building.

Rocks crumble under the tracks as the blade lowers and the vehicle inches forward.

The walls fold in, and the second story buckles as the driver works his way around the structure.

We watch as the home is slowly compressed into a pile of twisted rebar, broken cinder blocks, and tattered belongings.

We cheer.

I notice that our interpreter does not.

The insurgents go silent.

But 20 years later, I still hear them scream.

We continue our patrol back to base.

It’s time for chow.

Later that week, the streets are quiet. We move between houses and narrow alleyways, expecting to come under attack for hours. Nothing.

As we are turning back to base, a shot rings out. Then another. Sniper. I’m a few doors down and want to fire a rocket into the building, but Marines are ordered to storm the compound instead.

Two Marines from our platoon, Bradley Faircloth and Michael Meadows, push through the gate and clear the courtyard. They notice the windows are covered with blankets and that the front door is unlocked.

As they step into the living room, there’s a stairway to their left and two rooms in front of them. One door is open. The other closed.

Faircloth leads Meadows down the hallway—he’ll go left. Meadows goes right.

As they walk toward the doors, a machine gun erupts with a 20-round burst. Faircloth moans as he collapses to the floor.

Meadows sprints through the open door and calls for reinforcements. Ryan Stulman and their squad leader, Evan Matthews, rush inside to clear the house, but the enemy fighters escape.

The three Marines grab Faircloth by his limbs and scream for a corpsman as they carry him outside.

Faircloth’s head bobs up and down with every step. His lips are blue. His eyes are open.

Corpsman up! Corpsman! CORPSMAN!

They set his body down in the courtyard, and our corpsman Reinaldo “Doc” Aponte begins his assessment. Airway. Breathing. Circulation.

Doc reaches to check for a pulse, and his fingers slip inside a wound on Faircloth’s wrist.

No pulse.

He tears open Faircloth’s flak jacket and sees gunshot wounds to his flank.

There’s very little blood.

No rise and fall of his chest.

Doc intertwines his fingers and centers his palm on Faircloth’s sternum.

Ribs and cartilage break with each two-inch-deep chest compression.

But Faircloth’s injuries are too extensive.

There’s nothing Doc can do to save his patient.

Doc has to be pulled off of Faircloth’s body.

Tears stream down his face as he is embraced by the Marines around him.

Doc is 21 years old.

Our platoon is scattered, and many of us don’t yet know Faircloth is dead.

The firefight continues.

Sgt. Anthony Martinez is on a nearby rooftop and shoots two fighters scurrying to a nearby building. Lt. Bahrns does the same. Robert Day pulls the trigger of his machine gun and fires at the house.

Then I see two insurgents sprint down an alleyway into a compound.

Squirters.

I shoulder my rocket launcher and fire in their direction. Three walls of the building collapse, and the house folds outward.

I run with three other Marines toward the collapsed structure and find two bodies lying outside, blown clear by the blast.

I stare at the figures. One is mangled and missing both legs. Blood pools beside his torso.

Then I hear someone yell out that a Marine has been killed storming the compound.

My eyes sting from sweat and tears of frustration.

Weeks of heavy combat have put me on edge. Friends have died; others have been wounded, some multiple times.

Now the enemy fighters lay dead on the ground in front of me.

I think to myself that if I had fired my rocket into the building, a Marine might still be alive.

We’re told it’s Lance Cpl. Bradley “The Barbarian” Faircloth, a 20-year-old from Mobile, Alabama. He’s a Sgt. Leo in the making and widely regarded as the best boot in the platoon.

We watch from a distance as the body bag is zipped closed and loaded into the back of a vehicle.

Many of us cry as we continue our patrol back to base.

When we return, there’s silence as we eat our vacuum-sealed meals of preservatives and congealed fats. Meadows wishes he’d thrown a grenade and killed the men who shot Faircloth. Matthews wonders if his squad will ever trust him again. Bahrns believes he let down Brad’s family back home.

Doc is inconsolable and believes he failed us by not saving Faircloth. That he’s lost our trust. And that by losing Faircloth, he’s lost us all.

All of us know there will be a memorial service when we get home and are scared about what it will be like to look Bradley’s mother in her eyes.

As the days go on, we reminisce about Faircloth and the Thanksgiving dinner we shared with him the day before he was killed. Our loss of motivation is palpable. We want to go home. But we still have two months left on our deployment.

Over the next few weeks, Leo nominates roughly half of our squad for valorous awards. The Corps’ bureaucracy mows most of them down.

The next month, our battalion commander Lt. Col. Gareth Brandl begins making his rounds to talk to Marines across the battlespace. We take out the trash and shave our faces. We blouse our boots and put on our cleanest uniforms. It’s our turn for the dog and pony show.

When he arrives, we stand neatly in a formation as he speaks for what seems like an hour—stories of our bravery and sacrifice and how we upheld the Corps’ legacy.

Yut. Err. Kill.

One sentence lingers in our minds. Prepare for your next mission.

Widows and other Gold Star family members sit in the front rows of a silent theater.

It’s the spring of 2005, and we’ve been home for a few weeks. Our entire battalion is crammed into the base field house at Camp Lejeune. Dozens of portraits are displayed on the floor, each paired with a rifle, dog tags, and boots.

I stare at the photographs. They stare back.

They’re all dead.

For months, we’ve struggled with our battle, but we’ve remained isolated from the families who received the dreaded knock on the door to mark the start of their holiday season. We weren’t there for their three-volley-gun salute, or when they were handed a folded flag “on behalf of a grateful nation.”

Now, seated in the bleachers, we are too far away to comfort them.

Doc can’t bear to watch Kathleen Faircloth walk across the floor. He sneaks outside and cries in the cab of his truck.

I sit quietly and recall my times at the School of Infantry with Demarkus Brown, who loved to tell stories about his mother.

I think back to my conversations with Lt. Malcom about his sister.

I remember my late-night conversations with Travis Desiato about being proud Massholes.

I think about how much I want to apologize to Kathleen Faircloth, but I can’t face her.

One by one, the families are ushered across the floor, and one by one, they stand by the photographs of their loved ones. Some pray. Others hug. Most of them cry.

Children with no fathers. Parents who lost sons. Families destroyed. Friends we’ll never see again. All torn apart by combat thousands of miles away during a war that America ignored.

As each family walks back to their seats, the steady rhythm of their footsteps is a reminder of how we failed to bring their loved ones home.

The sound of taps fills the building.

I stare straight forward and try not to let anyone see me crying. It’s a feeling I’ll get used to.

Twenty years ago, I thought the Corps gave me exactly what I asked for, and I’m still struggling to understand the meaning of it all.

When I enlisted in 2003, I was a rebellious teenager who lacked discipline and a sense of purpose. Despite my mother’s objections, I wanted to be a Marine infantryman. When I got to recruit training at Parris Island, the Corps handed me my first rifle and taught me that blood makes the grass grow. In Fallujah, we destroyed our enemy through fire and maneuver—exactly what we were trained to do.

The rules of engagement justified the death and destruction. But today, I no longer can.

When we came home, we settled into the monotony of grocery shopping, changing diapers, and paying utility bills, all while we faced a rampant stigma disincentivizing mental health care. Dozens of Marines across our battalion self-medicated with drugs and alcohol. Those who were caught were publicly shamed and booted from the Corps.

I eventually tried to kill myself.

The fog of war may have been in Fallujah, but it still drifts in and out of our lives, often at the most inopportune, unexpected times.

Like the time my daughter and I were playing with dolls on the floor and their cold, lifeless eyes reminded me of a dead body.

Or when the scent of jet fuel at the airport made me imagine running alongside a tank, smiling with my friends.

Or when AC/DC’s “Hells Bells” came over the speakers as my wife and I waited in line to ride a roller coaster. My mind drifted to crossing Route Fran, and memories of Malcom and Faircloth.

I stared straight forward and tried not to let anyone see me crying. The feeling I’m now used to.

And now, after two decades spent trying to forget what we saw and did in Fallujah, I decided it was time to confront it. I reached out to Marines I hadn’t spoken to since the battle, and with them by my side—just like they were 20 years ago—I wrote this story.

In August, I organized a five-day reunion in DC that brought our squad back together. We cried. We laughed. And we remembered. But the most healing part of our time together was that Faircloth’s mother, Kathleen, traveled from Alabama to join us and lead us into the new Fallujah exhibit at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

Together, we listened to her read the last letter Bradley wrote home.

And not only were we able to look Kathleen in the eye but she told us something that will never leave me.

We are all her sons.

Like millions of Americans, I volunteered to serve during a time of war and knew I might experience combat. We trusted the Pentagon officials leading us and the promise that we’d be cared for once we returned home. We believed the global war on terror was justified and that by fighting it, our children wouldn’t face the same enemy. We believed Americans cared about the war we fought on their behalf.

We should have known better.

After 20 years, what haunts me most about Fallujah isn’t just the killing or how we did it, whether it was a bullet, a blast, or a bulldozer.

It’s knowing that some of the hope we destroyed in Fallujah was our own.

The hope that time will make the memories fade away.

The hope that I’ll forgive myself.

And the hope that it was all worth it in the end.

If you or someone you care about may be at risk of suicide, contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988, or go to 988lifeline.org.

The People Who Made This Project Possible

Author

Thomas J. Brennan

Photography

Matt Eich

Justin Gellerson

Cpl. Trevor Gift

Madison Brennan

Video

TJ Cooney

Sunjae Smith

Shane Yeager

Claude Robinson

John Napolitano

Greg Corombos (AVC)

Dan Taksas (AVC)

Peter Trahan (AVC)

Vallen King (AVC)

Rich McFadden (AVC)

Nick Schifrin (PBS Newshour)

Paul Wood (BBC Embedded Footage)

Robbie Wright (BBC Embedded Footage)

Audio

Elena Boffetta

Jim O’Grady (Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting)

Engagement

Lydia Williams Keller (Soundview Creative)

Hrisanthi Kroi Pickett

Fact-Check

Jess Rohan

Copy Edits

Mitchell Hansen-Dewar

Editors

Mike Frankel

Dan Schulman (Mother Jones)

Music Licensing

Jonathan Leahy, Aperature Music (In-Kind Advisory Support)

Phil Collins via Concord Publishing and Warner Music Group (Gratis)

Lynyrd Skynyrd via UME and UMPG (Gratis)

AC/DC via Sony and Sony Music Publishing (Gratis)

Partners

Mother Jones

PBS NewsHour

The Center for Investigative Reporting

The American Veterans Center

Location Support

Lt. Col. Matthew Hilton, USMC Communications Directorate, New York

Col. John Caldwell, Communications Directorate, Headquarters USMC

The National Museum of the Marine Corps

Office of the Secretary of Defense

The United States Marine Corps

Mental Health

Dr. Pamela Wall

Jodi Salamino

Legal Review

BakerHostetler

James Chadwick (Mother Jones)

Four Retired Marine Judge Advocates

Financial Support

Semper Fi Fund

Anne Lebleu

Fred Smith

Mike Zak

Compass Coffee

The Reva and David Logan Foundation

The Heinz Endowments