Long before Instagram and TikTok existed as places for us to stoke our insecurities, there was Martha Stewart. Martha, circa 1995, smiling from the pages of her namesake magazine as she put the finishing touches on a Versailles-worthy pastel cake. Martha, again in the mid-1990s, ably demonstrating the only proper way to prune an unruly tree. Martha, in early 2004, the picture of quiet luxury in her downy, twig-colored woolens as she strode into the Manhattan federal courthouse during her trial on nine criminal counts associated with the ImClone insider-trading scandal. You could love her, you could hate her, you could love to hate her or vice versa. Her mission, it seemed, was twofold: to teach you how to do seemingly unachievable things around the home, and to make you feel inadequate.

But if Martha Stewart gave many of us our first taste of feeling terrifically ill-suited to any domestic task or even just to basic living, she also inadvertently reminded us that when it comes to nurturing self-confidence, we’re our own worst enemies. Her confidence and drive for perfection made us feel bad; we decided our hurt feelings were her fault. But now—when our social media feeds are filled with beautiful people doing remarkable things that most of us will never be able to pull off, or afford—it’s time to reconsider the rise, fall, and rise of Martha Stewart. The degree to which she both inspired and angered so many of us is still something to reckon with. As Eleanor Roosevelt said, “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.”

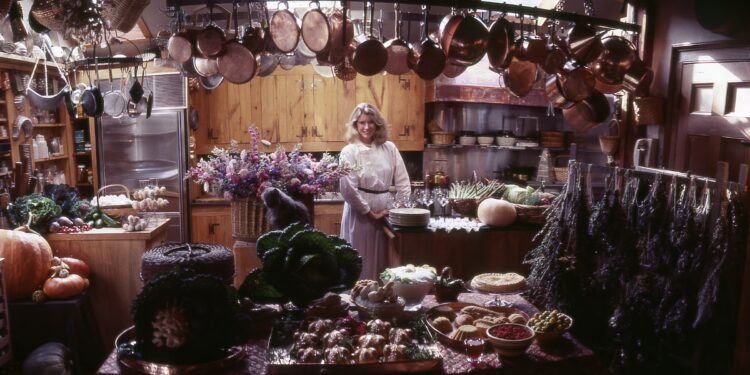

If you still need convincing that Martha Stewart is a human being much like the rest of us—albeit one who can cook a turkey inside a puff pastry without once bursting into tears—R.J. Cutler’s documentary Martha, streaming on Netflix, should do the trick. Stewart has done some remarkable things: She worked as a teenage model. She was a stockbroker in the late 1960s, a rarity for a woman at the time. She launched a successful catering business in 1973. That spurred the release of her first cookbook, 1982’s Entertaining, which led to television appearances and more books. By the late 1990s, she had built herself into a juggernaut of a brand; she was the first woman in the United States to become a self-made billionaire.

But her background was hardly privileged. Martha introduces us to young, fresh-faced Martha Kostyra, one of a family of six kids growing up in Nutley, N.J., in the 1940s and ’50s. Her mother taught her about home-making; her perfectionist father passed his love of gardening on to her. Stewart acknowledges she was her father’s favorite; like him, she was a stickler for details. But her childhood and youth weren’t easy. The family was often broke, so Stewart needed that modeling money: the $15 per hour it brought in made a world of difference. After graduating from high school, she enrolled at Barnard and began dating Andy Stewart, the brother of a fellow student. The two married in 1961. They had a daughter, Alexis, and eventually bought and restored an old farmhouse in Westport, Conn. The property became both proof of Stewart’s homemaking-skills-in-overdrive and an inspiration to millions of others who hoped to work the same magic in their own homes.

But the marriage fell apart, and even Martha Stewart—poised, sometimes, to the point of frostiness—has a heart to break. Perfectionists are also often idealists; dashed expectations can crush them. “I always said I was a swan,” she says on camera, noting that swans are monogamous. “I thought monogamy was admirable … but it turned out it didn’t save the marriage.” She pauses. Her expression shifts from wistfulness to something more resolute before she says, “Can we get on to a happier subject?”

But then, Stewart—not as perfect as we may have thought—also admits on camera to having had an adulterous affair herself, though she notes that it was fleeting. As a documentarian, Cutler knows how to nudge his subjects into being perhaps a little more revealing than they’d like. His superb 2009 documentary The September Issue pulled back the curtain on the inner workings of Vogue magazine, as orchestrated by the indomitable Anna Wintour. Stewart is an even better subject for Cutler, because she, unlike Wintour, fell from a very high perch—and not only recovered but also managed to transform into a better version of her old self. In 2005, Stewart was sentenced to five months in prison, for lying to the FBI when she was questioned about her involvement in the ImClone case. Her early days at West Virginia’s Alderson Federal Prison Camp were bleak. Her compatriots found her aloof, and some wanted to hurt her. She spent a day in solitary confinement for inadvertently touching a prison officer. The food was the opposite of fresh. Her boyfriend at the time, software billionaire Charles Simonyi, visited her only once. (Not long after her release, he abruptly dropped her.) “I feel very inconsequential today,” she wrote in her journal, in the early days of her incarceration. “As if no one would miss me if I never came back to reality.”

There’s probably someone out there who delights in knowing that the always perfect Martha Stewart ever felt this low. But would you really want to meet that person? In the 1980s and ’90s, Stewart was an easy target for mass derision and mockery, on Saturday Night Live and everywhere else. And in some ways, she invited it: she really did come off as smug. But no one in her 80s is the same person she was in her 20s, 50s, or 60s. And not even Martha Stewart is still the Martha Stewart we knew from her earlier books, magazines, and television shows. In Martha, she appears on camera in a silky black blouse trimmed with a simple neckband of tiny, discreetly sparkly stones. Her fair, dewy skin looks better than just “young.” Rather, it’s ageless in a suitably age-appropriate way. This is also a woman who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue at age 81, wearing only a simple white bathing suit and a drape made of apricot taffeta. Her smile is both daring and darling, as if she’s harboring a valuable secret gleaned from years of experience—though she’s not giving it away for nothing.

Cutler’s documentary, though, spills some of those secrets for her. It shows us, through re-enactments rendered in drawings, how Stewart made the most of her time in prison. She gave talks, advising the other women on how they might start their own businesses after their release. She cleaned bathrooms. She made sure she learned something new every day. And when her sentence was complete, she stepped back into the world wearing a swingy-chic poncho that a friend and fellow inmate had hand-crocheted for her. DIY devotees grabbed their hooks and eagerly made their own versions.

That poncho was a symbol of something Stewart had always stood for, even though many had over the years misread—and even been angered by—her message. Stewart believed in the democracy, and the pleasure, of the “domestic arts,” historically the province of women. She wanted us to know that those skills, long considered inferior to manly pursuits, had value. You could learn to crochet. You could use gold leaf to make an Easter egg worthy of a king. You could assemble a bunch of garden flowers in an earthenware vase and make it look like a million bucks. Your results might not be as perfect as Martha’s, and she probably knew that as well as you did. But maybe setting the bar high was a sign of respect for her audience, rather than condescension. Really, she just wanted you to try.

The subtext of Martha is that Stewart has been punished enough. She’s earned her day in the sun. And sure enough, today, almost everyone loves her. Her Instagram account—complete with “thirst trap” selfies and photos taken with one of her besties, Snoop Dogg—is a delight. Her 100th cookbook will be published this month. And maybe now those of us who once snickered at her dogged pursuit of perfection, or delighted in hearing that she wasn’t a particularly nice person—I confess I used to be one of them—can see that we were participating in an insidious form of misogyny. As her son-in-law, lawyer John Cuti, puts it in Martha, “She was a tough boss, but some of the behavior that she would be taken to task for would be applauded if a man did it in the business world. That’s a cliché at this point, but it doesn’t mean it wasn’t true.”

We also see vintage 1990s footage of Owen J. Lipstein, the editor in chief of the ever sardonic Spy magazine, making this lofty pronouncement: “The more you know about this woman, the less you like her.” Being liked: it’s what every woman wants. Right? Yet maybe Stewart—particularly the younger, bolder, world-conquering Stewart, who asked for everything she wanted even as men in power tried to block her—didn’t care so much. And today, the more we know about this woman, the more we like her. She no longer makes us feel bad about ourselves. Because after all, it has always been our job, not hers, to guard our self-worth. And if, along the way, we learned something about how to make exceptionally lifelike fondant butterflies, daisies, or forget-me-nots? That was just the icing on the cake.