BELLEAIR BEACH, Fla. — Florida’s storm-battered Gulf Coast raced against a Category 5 hurricane Monday as workers sprinted to pick up debris left over from Helene two weeks ago and highways were clogged with people fleeing ahead of the storm.

The center of Hurricane Milton could come ashore Wednesday in the Tampa Bay region, which has not endured a direct hit by a major hurricane in more than a century. Scientists expect the system to weaken slightly before landfall, though it could retain hurricane strength as it churns across central Florida toward the Atlantic Ocean. That would largely spare other states ravaged by Helene, which killed at least 230 people on its path from Florida to the Carolinas.

“This is the real deal here with Milton,” Tampa Mayor Jane Castor told a news conference. “If you want to take on Mother Nature, she wins 100% of the time.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said Monday that it was imperative for debris from Helene to be cleared ahead of Milton’s arrival so the pieces cannot become projectiles. More than 300 vehicles gathered debris Sunday.

As evacuation orders were issued, forecasters warned of a possible 8- to 12-foot (2.4- to 3.6-meter) storm surge in Tampa Bay. That’s the highest ever predicted for the region and nearly double the levels reached two weeks ago during Helene, said National Hurricane Center spokesperson Maria Torres.

The storm could also bring widespread flooding. Five to 10 inches (13 to 25 centimeters) of rain was forecast for mainland Florida and the Keys, with as much as 15 inches (38 centimeters) expected in some places.

The Tampa metro area has a population of more than 3.3 million people.

“It’s a huge population. It’s very exposed, very inexperienced, and that’s a losing proposition,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology meteorology professor Kerry Emanuel said. “I always thought Tampa would be the city to worry about most.”

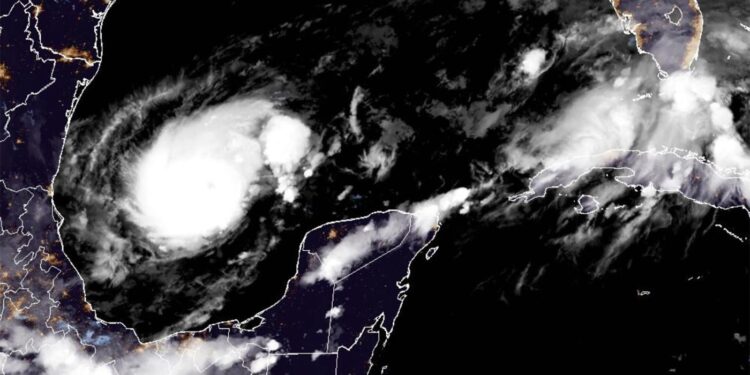

Much of Florida’s west coast was under hurricane and storm surge warnings. A hurricane warning was also issued for parts of Mexico’s Yucatan state, which expected to get sideswiped.

Milton intensified quickly Monday over the eastern Gulf of Mexico. It had maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (285 kph), the National Hurricane Center said. The storm’s center was about 675 miles (1085 kilometers) southwest of Tampa by late afternoon, moving east-southeast at 10 mph (17 kph).

The Tampa Bay area is still rebounding from Helene and its powerful surge. Twelve people died there, with the worst damage along a string of barrier islands from St. Petersburg to Clearwater.

‘It’s going to be flying missiles’

Lifeguards in Pinellas County, on the peninsula that forms Tampa Bay, removed beach chairs and other items that could take flight in strong winds. Elsewhere, stoves, chairs, refrigerators and kitchen tables waited in heaps to be picked up.

Sarah Steslicki, who lives in Belleair Beach, said she was frustrated that more debris had not been collected sooner.

“They’ve screwed around and haven’t picked the debris up, and now they’re scrambling to get it picked up,” Steslicki said Monday. “If this one does hit, it’s going to be flying missiles. Stuff’s going to be floating and flying in the air.”

Hillsborough County, home to Tampa, ordered evacuations for areas adjacent to Tampa Bay and for all mobile and manufactured homes by Tuesday night.

President Joe Biden approved an emergency declaration for Florida, and U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor said 7,000 federal workers were called on to help in one of the largest mobilizations of federal personnel in history.

Many evacuate, but some are reluctant

Milton’s approach stirred memories of 2017’s Hurricane Irma, when about 7 million people were urged to evacuate Florida in an exodus that jammed freeways and clogged gas stations. Some people who left vowed never to evacuate again.

By Monday morning, some gas stations in the Fort Myers and Tampa areas had already run out of gas. Fuel continued to arrive in Florida, and the state had amassed hundreds of thousands of gallons of gasoline and diesel fuel, with much more on the way, DeSantis said.

A steady stream of vehicles headed north toward the Florida Panhandle on Interstate 75, the main highway on the west side of the peninsula, as residents heeded evacuation orders. Traffic clogged the southbound lanes of the highway for miles as other residents headed for the relative safety of Fort Lauderdale and Miami on the other side of the state.

Candice Briggs, along with her husband, their three young kids and their dog, planned to head to a hotel north of Jacksonville less than two weeks after Helene sent a foot and a half of water into her family’s home in the in the Tampa Bay community of Seminole. The family had just settled into their temporary lodgings at an extended family member’s home when they had to evacuate again before even finishing their post-Helene loads of laundry.

“Most of the tears I’ve cried have been out of exhaustion or gratitude. Just that we’re safe and that we followed our instincts to evacuate,” Briggs said. “Mostly I am grateful. But I am overwhelmed and I am exhausted.”

Briggs was worried about her storm-damaged house, where workers have already torn out feet of sodden drywall, leaving behind exposed beams she fears will be even more vulnerable to the towering wall of water that forecasters say Milton could lash against the flood-prone stretch of the Gulf Coast.

Even though Tanya Marunchak’s Belleair Beach home was flooded with more than 4 feet (1.2 meters) of water from Helene, she and her husband were unsure if they should evacuate. She wanted to leave, but her husband thought their three-story home was sturdy enough to withstand Milton.

“We lost all our cars, all our furniture. The first floor was completely destroyed,” Marunchak said. “This is the oddest weather predicament that there has ever been.”

In Mexico, dozens of residents and tourists lined up with suitcases to catch an evacuation ferry off Holbox island on the eastern tip of the Yucatan Peninsula, popular for its shallow seascapes. The low-lying, flood-prone island may be one of the closest points that Hurricane Milton brushes before moving toward Florida.

Off-and-on resident Marilú Macías, joined by her daughters, was calm and smiling but afraid of what Milton could do.

“We are afraid something might happen to us,” she said. “We’re going someplace safer.”

Why did Milton intensify so fast?

Milton’s wind speed increased by 92 mph (148 kph) in 24 hours — a pace that trails only those of Hurricane Wilma in 2005 and Hurricane Felix in 2007. One reason Milton strengthened so rapidly is its small “pinhole eye,” just like Wilma’s, said Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach.

The storm will likely go through what’s called an “eye wall replacement cycle,” a natural process that forms a new eye and expands the storm in size but weakens its wind speeds, Klotzbach said.

The Gulf of Mexico is unusually warm right now, so “the fuel is just there,” and Milton probably went over an extra-warm eddy that helped goose it further, said University of Albany hurricane scientist Kristen Corbosiero.

The last hurricane to be a Category 5 at landfall in the mainland U.S. was Michael in 2018.

Widespread cancellations in Florida and Mexico

With the storm approaching, schools in Pinellas County, home to St. Petersburg, were being converted into shelters. Airports in Tampa, St. Petersburg and Orlando planned to close. Walt Disney World said it was operating normally for the time being.

In Mexico, Yucatan state Gov. Joaquín Díaz ordered the cancellation of all nonessential activities except for grocery stores, hospitals, pharmacies and gas stations starting Monday, and Mexican officials organized buses to evacuate residents from the coastal city of Progreso.

It has been two decades since so many storms crisscrossed Florida in such a short period of time. In 2004, an unprecedented five storms struck Florida within six weeks, including three hurricanes that pummeled central Florida.

Schneider reported from Orlando. Associated Press writers Kate Payne in Tampa, Terry Spencer in Fort Myers Beach, Freida Frisaro in Fort Lauderdale, Seth Borenstein in Washington, Brendan Farrington in Tallahassee and Mark Stevenson in Mexico City contributed to this report.