The MTA’s board formally approved the transit agency’s $68.4 billion ask for the next five years for big-ticket projects, unanimously backing the capital budget by a vote of 10-0.

As previously reported, the budget includes a massive $10.9 billion earmarked for new subway and commuter rail cars, and nearly $25 billion in so-called “state of good repair” work maintaining tracks, stations, signals, power and more.

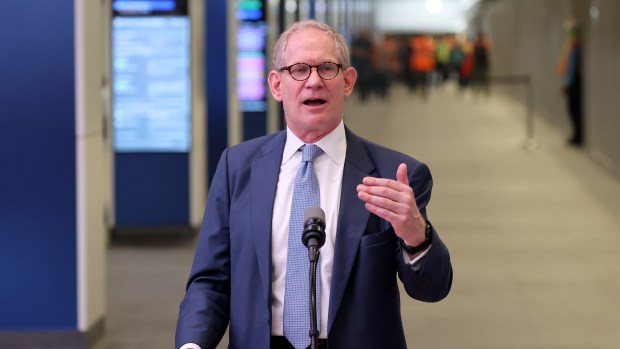

“Today was a big day. We’ve been planning for this moment for a couple of years now,” MTA Chairman Janno Lieber said following the vote.

PENN_STATION

Luiz C. Ribeiro/for New York Daily News Janno Lieber, MTA CEO. (Luiz C. Ribeiro/for New York Daily News)

The plan, meant to fund capital expenses from 2025-2029 is the largest in MTA history. The current 2020-2024 plan totaled $55.4 billion in projects.

The bulk of the plan focuses on repairing or replacing aging MTA assets — in particular the aging R-62 and R-68 subway cars that have served the city for four decades, the functionally obsolete M3 commuter rail cars, and a power grid where more than a third of substations are in poor condition.

“The spirit of this program is very conservative,” Lieber told reporters. “It’s focusing on protecting riders from a decline in service due to infrastructure that’s been, for whatever reason, neglected or left unfixed.”

MTA officials expect federal grants to cover about $14 billion of the plan. The MTA’s own bonds are expected to raise another $13 billion. State and local contributions are expected to total up to an additional $8 billion in funding.

That leaves the agency with a $33.4 billion funding hole. Lieber said he’s optimistic state lawmakers will step up.

“I think the folks who have [the] power understand that there is nothing that impacts New Yorkers’ lives more than the public transit system,” he said.

“New Yorkers depend more on public transit on a daily basis than any other governmental service or activity to enable their lives.”

The approved capital plan is due by Oct. 1 before the state’s MTA Capital Program Review Board, which has 30 days to review it.

The MTA still awaits word from Gov. Hochul how it will fund the remaining $15 billion in its current capital plan, which had been slated to come from bonds tied to the state’s congestion pricing program.

Originally Published: