(NEXSTAR) — Fall has officially begun, which means we’re just a few weeks away from one of America’s least favorite traditions: the end of daylight saving time.

While not a holiday, November’s changing of the clocks is often more celebrated than March’s, thanks in part to the fact that we gain an hour of sleep. Unfortunately, it also means we’re entering a time of earlier sunsets and colder temperatures. (The latter isn’t daylight saving time’s fault; they’re just correlated.)

Poll after poll and survey after survey have found that Americans, regardless of political party, dislike the bi-annual practice of changing the clocks and want to make daylight saving time permanent.

So why hasn’t the country united to freeze the clocks?

There have been efforts and, for a short time, the U.S. did stop changing the clocks twice a year.

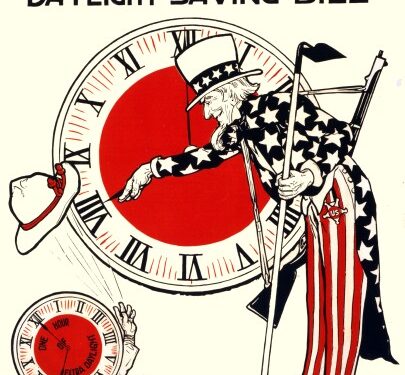

In 1918, the U.S. started observing daylight saving time as a wartime measure to save energy, but that lasted for only a year, according to the University of Colorado Boulder. It came back in 1942 during World War II, but was so chaotic as states and localities were allowed to decide when they wanted to switch between daylight saving and standard times.

Finally, in 1966, Congress passed the Uniform Time Act to standardize the twice-a-year changing of the clocks nationwide (with the exception of two states that opted out).

The U.S. has largely observed daylight saving time starting in March and ending in November the same way ever since, with the exception of a brief period in the 1970s that seemingly still influences politics today.

The year was 1973. The U.S. was facing a national energy crisis, and, in an effort to extend daylight hours and cut back on the demand for energy, President Richard Nixon signed an emergency daylight saving time bill into law. There was great public support for the move, at least at first.

Among those who quickly lost interest in the change were parents, who found themselves sending their children to school under the shroud of winter darkness. (In some parts of the country, the sun wouldn’t rise until after 8 a.m.) Less than a year later, President Gerald Ford signed a bill to put the U.S. back on standard time through the winter, as we are today.

In recent years, the push to put the U.S. on permanent daylight saving time year-round have resurfaced. Nearly every state has tried at least once to lock its clocks. Most, however, are hoping to stay on daylight saving time all year — an option not afforded to them under the Uniform Time Act of 1966. Several have passed bills to make daylight saving permanent in their states, should Congress give them permission, while others have passed resolutions calling on Congress to make the switch for the whole country.

It ultimately comes down to Congress on whether or not the U.S. continues to change its clocks twice a year. There have been multiple bills introduced during the current session of Congress, but all three have been stalled in committees.

Unless those or any subsequent bills make it through Congress soon, be prepared to gain an hour of sleep on November 3 when daylight saving time ends.

Jeremy Tanner contributed to this report.