When Governor Tim Walz was announced as Kamala Harris’ running mate, Ben Jealous, the Sierra Club’s executive director, released a statement hailing him as someone who “has worked to protect clean air and water, grow our clean energy economy, and see to it that we do all we can to avoid the very worst of the climate crisis.”

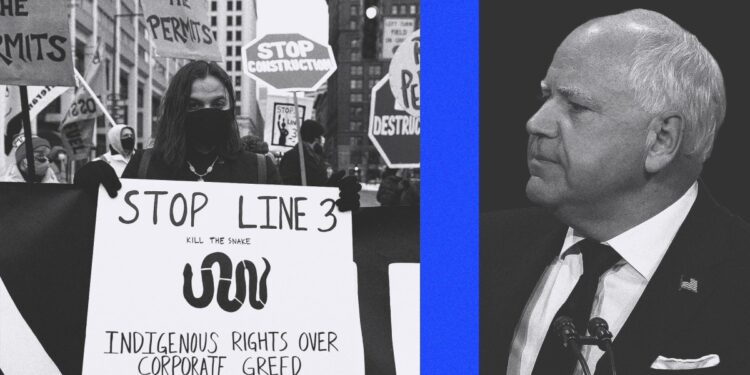

But to a group of Indigenous environmental activists familiar with Walz’ record in Minnesota—particularly their view he broke a promise to block the construction of Line 3, a cross-state oil pipeline—such a ringing endorsement of his green credentials rings hollow.

A few days after her home state’s governor joined the ticket, Tara Houska, an attorney and Indigenous rights activist, expressed that point of view in an Instagram video post where she said he had led “a brutal, multi-year campaign to suppress Indigenous people and allies trying to stop Line 3 tar sands.” It showed a clash between protesters and police at a Line 3 pipeline construction site over a soundtrack of rising drums. In the final scene, Houska is being escorted away by police while in restraints.

Houska first became involved in protesting pipelines in 2016 when, after working as a Native policy advisor for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, news about the Dakota Access Pipeline drew her back to the Midwest. After six months demonstrating against that pipeline at the Standing Rock reservation, Houska returned to the East Coast. She soon saw news coming out of the Midwest about a different pipeline: “I was like, ‘Oh, I need to go home.’”

The debate in Minnesota, which would lead to hundreds of demonstrators being arrested, came in the wake of major protests against the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines. The projects were opposed by environmental activists upset they would speed fossil fuel extraction and consumption, and by Indigenous communities concerned about the impact on their historic lands and waters.

The controversy dates back to April 2015, when Enbridge, a Canadian energy company, proposed to then Governor Mark Dayton’s administration a plan to replace an aging pipeline originally completed in 1968. The project, Enbridge argued, would address “integrity and safety concerns” and allow the company to transmit 760,000 barrels of oil per day. The proposed new route traveled from Canada to Minnesota’s border with Wisconsin, passing through state forests and the Fond du Lac Reservation, home to over four thousand members of the Lake Superior Chippewa.

Beyond climate-related concerns, opponents feared the pipeline would threaten water systems, especially wild rice beds, that Indigenous communities rely on. Enbridge’s track record includes two of the largest inland oil spills in national history. In 1991, Line 3 released 1.7 million gallons of crude oil in Northern Minnesota, and in 2010, another Enbridge pipe spilled over 1 million gallons in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

“We were sold one thing to vote for them…When we did vote, we were totally betrayed.”

Walz’s first public comments on the pipeline came in 2017, after Dayton announced he would not seek another term, and Walz, who had represented a southern Minnesota congressional district for 10 years, rolled out a campaign to succeed him. During a contested Democratic primary, Walz advocated against Line 3 by criticizing its harm to Native communities and lands.

“Any line that goes through treaty lands is a nonstarter for me,” he wrote on Twitter, adding that “every route would disproportionately and adversely affect Native people. Unacceptable.” His stand drew in support from the Indigenous community and environmentalists, reassuring voters who may have been troubled by his record in Congress, where he was just one of thirty Democratic members to vote in favor of the Keystone XL Pipeline.

“They got that extra push from climate folks and from tribal folks,” Houska recalled, explaining that Walz and his running mate, Peggy Flanagan, a member of the White Earth Nation, earned her vote in 2018.

Enbridge’s proposal, after years of reviews, appeals, and public forums, finally garnered the approval of Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission in June of 2018. But in the final weeks of Dayton’s term, his administration sued to overturn the decision, with the outgoing governor writing that he hoped to “ensure that a project with this magnitude of environmental impact upon our state serves the needs of our citizens.”

After Walz took office in early 2019, he said he would continue Dayton’s lawsuit, but in public remarks seemed to lay the groundwork to wash his hands of the issue, suggesting the project’s fate laid with an appeals court’s review of the commission’s decision. He explained he would not use executive powers to stop the pipeline “as a protection against the checks and balances being weakened.”

While Walz’ administration would continue to refile and support the suit Dayton launched, after a new environmental review, Enbridge was nonetheless able to obtain final permits and begin construction in December 2020. By early 2021, protests began to ramp up near Line 3 construction sites that would continue through the summer. In February, a group of tribal leaders asked Walz to enact an executive order to stop construction while litigation continued. At that point, a spokesperson for Walz said he did “not believe it is within his role to stay project permits that have been issued by state agencies after a thorough environmental review and permitting process.”

Houska says Walz passed the buck. “The reality is his administration could’ve stopped Line 3,” she argues, by upholding treaty obligations—specifically the Ojibwe nation’s unique right to harvest wild rice, which activists warned was threatened by the pipeline.

As opposition to the pipeline entered a new confrontational phase, demonstrators were met by a unique police force: the Northern Lights Task Force, which was made up of county law-enforcement agents whose time, training, and equipment were supported by a state account funded with $8 million from Enbridge. (Public records obtained by the Intercept show Walz hosted a conference call with senior task force members, and discussed its use of tear gas.) In addition to tear gas, rubber bullets, and other non-lethal weapons, police deployed “pain compliance” tactics that left multiple protestors partially paralyzed.

Walz’s choice of Flanagan, who had supported the Standing Rock pipeline protesters, as a running mate had been seen as a signal within Native communities that he would stand fast against the pipeline. “When it came through that he wasn’t doing anything, Peggy was very silent on the matter. She never showed up to rallies. Didn’t show up to the treaty camps,” says Dannah Thompson, an Anishinaabe anti-pipeline activist from Roseville, Minnesota.

As protest activity swirled, the lieutenant governor faced pressure to step in. Flanagan released a statement in July 2021 on Facebook: “While I cannot stop Line 3, I will continue to do what is within my power to make sure our people are seen, heard, valued and protected. Using my voice is an important part of that work.“

Walz’ administration did not respond to a request for comment. But in August 2021, just after a thousand Line 3 protestors picketed at the state capitol, Walz defended the project, by saying that while “we need to move away from fossil fuels… in the meantime if we’re gonna transport oil, we need to do it as safely as we possibly can with the most modern equipment.”

Construction only took about 10 months. (Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources has since documented multiple aquifer breaches that took place during building.) When tar sands began being pumped through the pipeline in the fall of 2021, MN350, a state climate justice non-profit, issued a blistering statement: “Shame on Governor Walz, who broke his campaign promise.”

“[We] fought as hard as we possibly could on every front: the ground fight, the regulatory fight, the political pressure, everything and anything to try to protect our wild rice and our waterways,” Houska said.

“Line 3 was an opportunity to prove that they wanted to take these bigger actions and stand up to financial powers and corporate powers,” says Thompson. “We were blindsided, and we were sold one thing to vote for them…When we did vote, we were totally betrayed.”

“There is a small faction of us that I know who aren’t able to move past this,” Thompson adds. Citing “the violence that was pushed towards Native people” by police, she says sorting through Walz’s record on the pipeline is a pre-election “conversation that is going to be had in the months coming up in the Native community.”